- Operating System as a Service

- Operating System User Interface

- System Call

- System Calls via API

- Types of System Calls

- Blocking vs Non-Blocking System Call

- Process Control

- Summary

- Appendix

50.005 Computer System Engineering

Information Systems Technology and Design

Singapore University of Technology and Design

Natalie Agus (Summer 2025)

Operating System as a Service

Detailed Learning Objectives

- Examine Operating System Services

- Explain the overarching role of the operating system in providing a platform for user interaction with computer systems through system calls and user interfaces.

- Identify and describe the basic support services provided by the operating system (types of system call), including resource sharing, program execution, I/O operations, file-system manipulation, process communication, and error detection.

- Utilize Operating System Interfaces

- Differentiate between the graphical user interface (GUI) and command-line interface (CLI) in operating systems, and explain how these interfaces facilitate user interaction with underlying system services.

- Describe ways on how to access OS services

- Explain how system calls are accessed via API

- Articulate the difference between making direct system calls vs through API

- Explain how parameters are passed to system calls

- Assess Network and Security Functions

- List out the protective measures and security mechanisms the operating system implements to guard against external threats and manage network interactions.

These objectives aim to guide your understanding of how operating systems provide essential services and interfaces that enhance user experience and system efficiency.

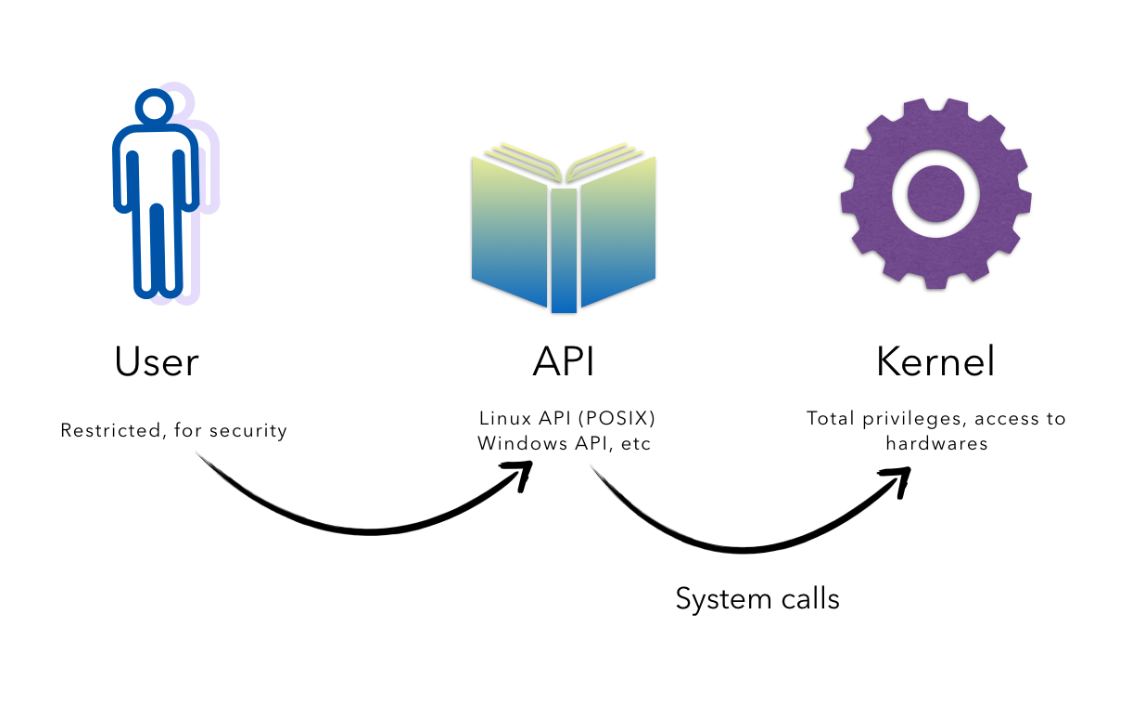

We learned about the overview of OS role in the past week. The kernel is just one part of an operating system. The entire operating system software itself is a much bigger one, and it provides various apps and functionalities to help users use the computer system.

User programs can make system calls whenever it needs to elevate its privileges and run in kernel mode to access the hardware or I/O devices.

In other words, the OS provides services for user programs. The goal of making an operating system us to allow users to use the computer system in an easier and more efficient manner.

Below are the brief list of operating system services that are usually provided to the users via the Operating System Interface: terminal and GUI. We will learn more about each of them this week

Basic Support

Basic support for computer system usage via system call routines:

- Program execution: The system must be able to load a program into memory and to run that program upon request. The program must be able to end its execution, either normally or abnormally (indicating error).

- I/O Operations: Being able to interrupt programs and manage asynchronous I/O requests.

- File-system manipulation: programs need to read and write files and directories. They also need to create and delete them by name, search for a given file, and list file information. Finally, some programs include permissions management to allow or deny access to files or directories based on file ownership.

- Process communication: Processes run in virtual environment. Communications may be implemented via shared memory or through message passing, in which packets of information are moved between processes by the operating system.

This include communication protocol via the internet, where processes in different physical computers can communicate.

- Error detection: The operating system needs to be constantly aware of possible errors. Errors may occur in the CPU and memory hardware (such as a memory error or a power failure), in I/O devices, etc. For each type of error, the operating system should take the appropriate action to ensure correct and consistent computing.

Sharing Resources

Diagnostics report and computer sharing feature:

- Resource sharing: When there are multiple users or multiple jobs running at the same time, resources must be allocated to each of them. Many different types of resources are managed by the operating system: CPU cycles, main memory, file storage, I/O device routines

- Resource accounting: This record keeping may be used for accounting (so that users can be billed) or simply for accumulating usage statistics.

Network and Security

Protection and security against external threats:

- All access to system resources is controlled.

- Defenses:

- To defend against potential threats coming from external I/O devices, including modems and network adapters that may make invalid access attempts

- To record network traffic and connections for detection of break-ins.

Operating System User Interface

Users can utilise the OS services in two general ways:

- Using the Operating system GUI or CLI (User Interface)

- By writing instructions and making system calls within the it (Programming Interface)

OS User Interface

The OS User interface gives users convenient access to various OS services. They are programs that can execute specialised commands and help users perform appropriate system calls in order to navigate and utilise the computer system.

GUI

The GUI or desktop environment is what we usually call our home screen or desktop. It characterises the feel and look of an operating system.

We use our mouse and keyboard everyday to interact with the OS GUI and make various system calls, for instance:

- Opening or closing an app

- File creation or deletion

- Get attached device input or output

- Install new programs, etc

When interacting with the OS through the GUI, users employ a mouse-based window-and-menu system characterized by a desktop metaphor:

- The user moves the mouse to position its pointer on images, or icons, on the screen (the desktop) that represent programs, files, directories, and system functions.

- Depending on the mouse pointer’s location, clicking a button on the mouse can launch a program,

- Select a file or directory (folder) or pull down a menu that contains commands.

In fact, anything that is performed by the user that involves resource allocation, memory management, access to I/O and hardware, and system security requires system calls. Operations to perform various system calls are made easier with the OS interface and more convenient with the OS GUI.

Obviously, the GUI is made such that general-purpose computers are user friendly.

You can customise your Ubuntu Desktop environment if you wish. By default, it comes with GNOME (3.36, at the time of current writing) desktop, but nothing can stop you from installing other desktop environments.

CLI

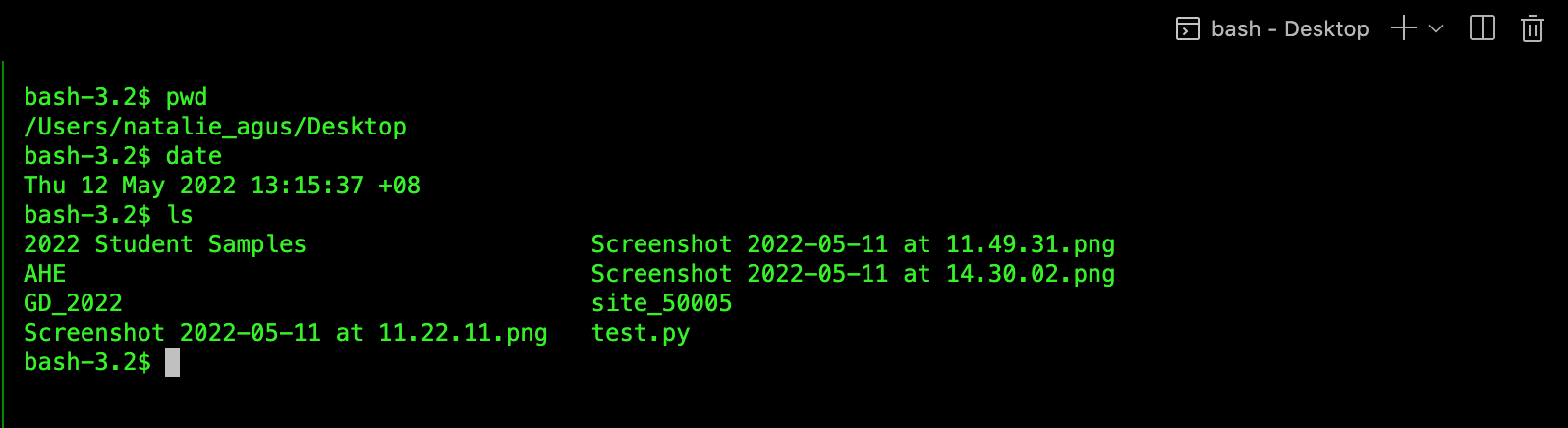

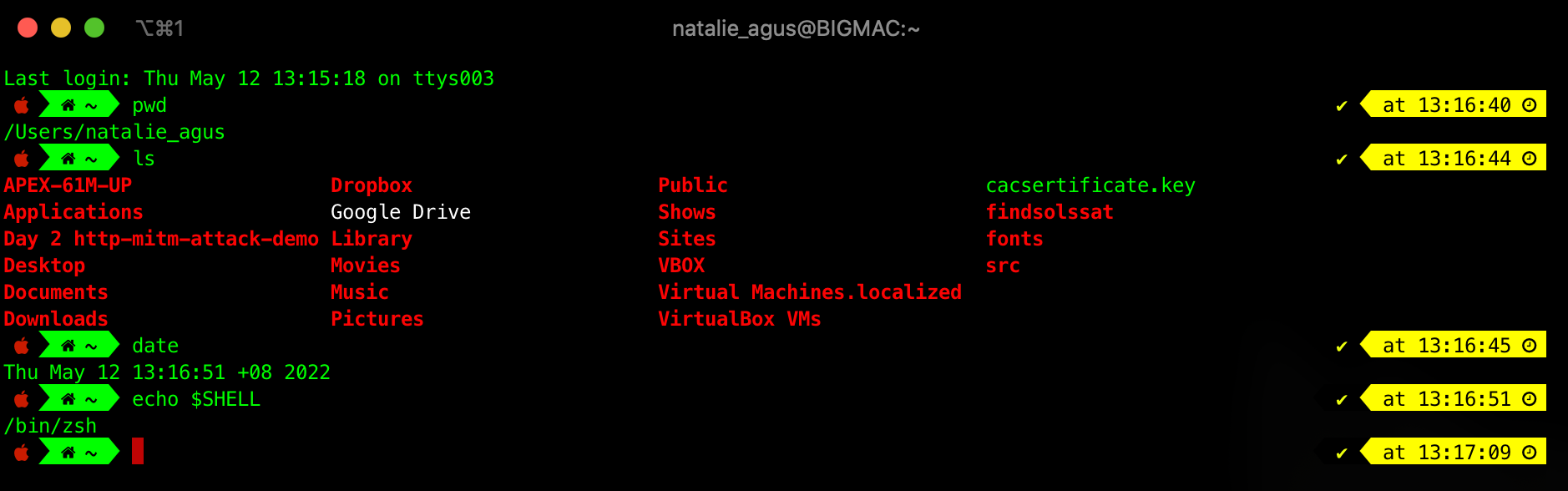

The OS CLI (Command Line Interface) is what we usually know as the “terminal” or “command line”.

CLI provides means of interacting with a computer program where the user issues successive commands to the program in the form of text. The program which handles this interface feature is called a command-line interpreter. We have experimented with this during Lab 1.

Command Line Interpreter

In UNIX systems, the particular program that acts as the interpreters of these commands are known as shells1. Users typically interact with a Unix shell via a terminal emulator, or by directly writing a shell script that contains a bunch of successive commands to be executed.

For a system that comes with multiple command line interpreters (shells), a user may choose which one to use. Common shells are the Bourne shell, C-shell, Bourne-Again shell, and Korn shell.

- Bourne-Again shell (bash): written as part of the GNU Project to provide a superset of Bourne Shell functionality. This shell can be found installed and is the default interactive shell for users on most Linux distros and macOS systems.

- Z shell (zsh) is a relatively modern shell that is backward compatible with bash. It’s the default shell in macOS since 10.15 Catalina.

- PowerShell – An object-oriented shell developed originally for Windows OS and now available to macOS and Linux.

In short, the shell primarily interprets a series of commands from the user and executes it. There are two ways to implement commands:

- Built-in: the command interpreter itself contains the code to execute the command.

- For example, a command to delete a file may cause the command interpreter to jump to a section of its code that sets up the parameters and makes the appropriate system call.

- In this case, the number of commands that can be given determines the size of the command interpreter, since each command requires its own implementing code.

- System programs (typically found in default

PATHsuch at/usr/bin): command interpreter does not understand the command in any way; it merely uses the command to identify a file to be loaded into memory and be executed. This is used by UNIX, among other operating systems.- You can type

echo $PATHon your terminal to find out possible places on where these system programs are.

- You can type

You will be required to implement a shell in Programming Assignment 1.

Terminal Emulator

A terminal emulator is a text-based user interface (UI) to provide easy access for the users to issue commands. Examples of terminal emulators that we may have encountered before are iTerm, MacOS terminal, Termius, and Windows Terminal.

Almost every system-administrative actions that we can perform on the OS GUI can be done via the CLI. For example, if we want to delete a file in different locations using the OS GUI, we need to perform the following steps:

- Hover our mouse to click folder after folder until we arrive at a final folder where the target file resides

- Right click, press delete (or use keyboard shortcut)

- Repeat until all files are deleted in various paths

Equivalently, we can perform the same action using the CLI. In UNIX systems, we can write the following commands in our terminal emulator:

cd <path>rm <filename>

Executing Commands

From Lab 1, you should’ve had the experience in trying out some simple shell commands. The implementation of the two commands cd and rm are as follows:

- The first line is implemented within the shell program itself (changing directory with

chdirsystem call). - The second line will tell the shell to search for a system program named

rmand execute it with the parameter<filename>.- System Programs are simply programs that come with the OS to help users use the computer. They are run in user mode and will help users make the appropriate system calls based on the tasks given by the users. More about System Program will be explained in the latter part.

- The function associated with the

rmcommand (removing a file) would be defined completely within the code in the program calledrm. - In this way, programmers can add new commands to the system easily by creating new system programs whose name matches the command.

- The command-interpreter program, which can be small, does not have to be changed for new commands to be added.

From Lab 1, you should have been able to find out where your system programs like ls, mkdir, rm, pwd, ps reside.

System Call

Besides using the GUI, we can access OS services using its programming interface (system calls), meaning that we develop our own programs that rely on OS services to utilise the computer system’s hardware and I/O devices.

System calls are programming interfaces provided by the OS Kernel for users to access kernel services. Unlike I/O interrupts, system calls are software generated interrupts (trap instruction).

When application programs make system calls, the execution of its original instruction is temporarily suspended and switches to the Kernel mode to execute the system call routine. System calls are one of the controlled entry points to the kernel (besides interrupts and reset), meaning that we cannot make our program such that our PC directly executes arbitrary parts of the kernel space. System calls are the only way for user-mode processes to change into kernel-mode processes via software instructions.

This is usually supported by :

- Hardware, e.g.: PC cannot perform

JMPto code with raw RAM addresses starting with MSB of ‘1’ - Virtualisation, user programs operate on virtual memory

System calls are mostly accessed by programs through APIs (application program interface), although we can certainly make system calls directly in assembly. There are plenty of examples in the next few sections.

A system call does NOT generally require a full context switch; instead, it is processed in the context of whichever process invoked it.

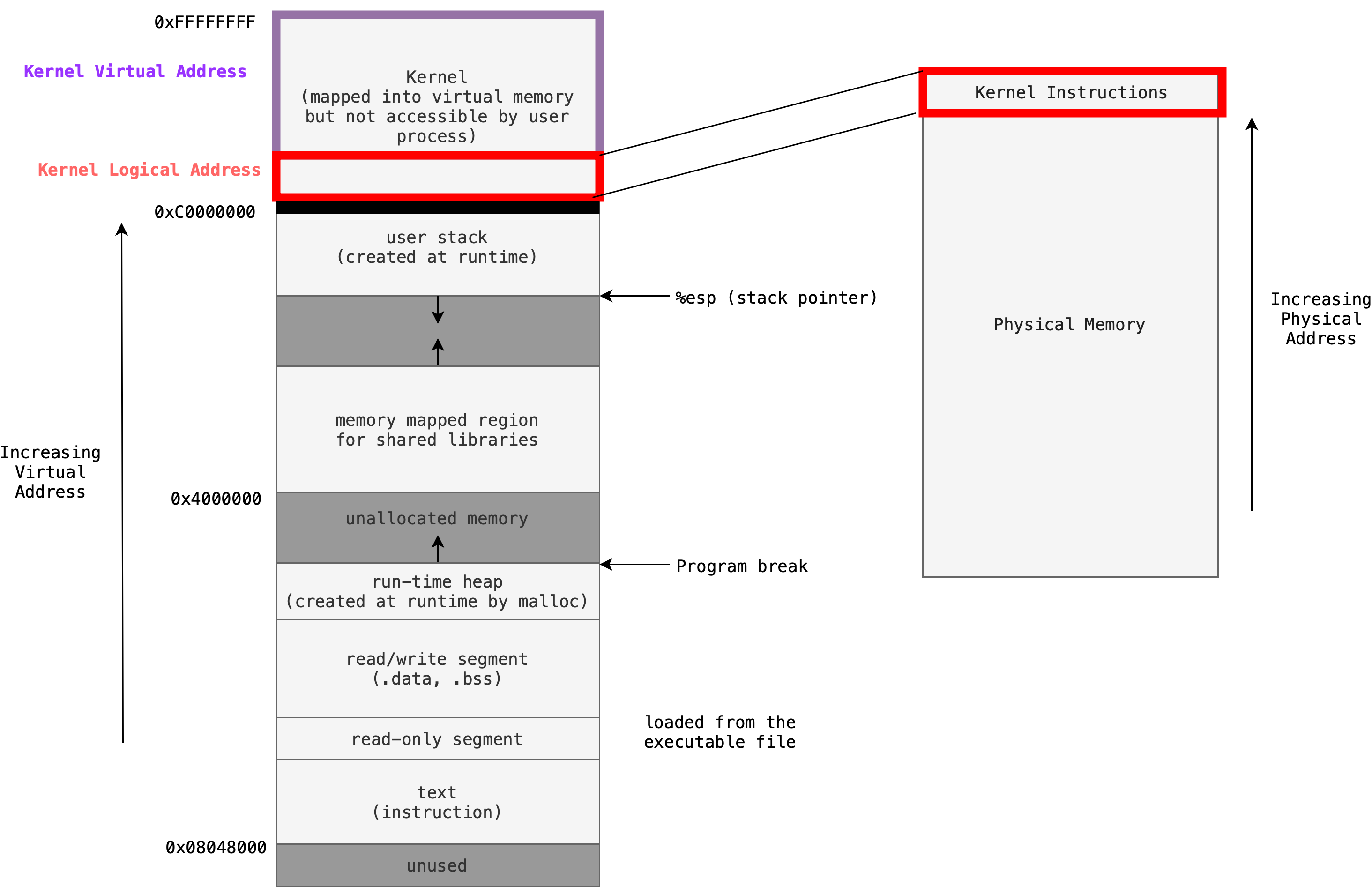

Accessing System Calls

Take this section with a grain of salt. It is not part of the syllabus but it is handy for you to understand how a regular user process can access kernel code via system calls.

All processes running in a computer must be able to make system calls. As a result, at the minimum the entry points into the kernel have to be mapped into the current address space at all times.

To provide you with a context, let’s see a typical memory layout2 of a UNIX process (actual implementation may vary, e.g. Kernel is at low address space instead):

The virtual address space of a process is typically divided into two parts: kernel part in the higher address and user part in the lower address (or vice versa, depending on the Kernel implementation).

The kernel mapping part exists primarily for the kernel-related purposes, not user processes. Processes running in user mode don’t have access to the kernel’s address space (with different MSB), at all. In user mode, there is a single mapping for the kernel, shared across all processes, e.g: fixed address between 0xffffffff to 0xC0000000 as illustrated above.

When a kernel-side page mapping changes, that change is reflected everywhere. Read more about Kernel Space in the appendix if you’d like to find out more. Recall that you have already learned this before as well in 50.002. You can read detailed info such as the null space or the memory mapped region in 50.002 notes here.

System Calls via API

One of the most common ways to make system calls is through an API (Application Programming Interface). We can write a program in a particular language and conveniently perform several system calls through the provided APIs supported by the chosen language as needed.

API is an interface that provides a way to interact with the underlying library3 that makes the system calls, often named the same as the system calls they invoke.

An API specifies:

- a set of functions that are available to an application programmer

- the parameters that are passed to each function and

- the return values the programmer can expect

3 most common APIs available:

- Win32 API for Windows systems written in C++

- POSIX API for POSIX-based system (all versions of UNIX); mostly written in C. You can find the functions supported by the API here

- Java API for programs running on Java Virtual Machine (JVM)

Behind the scenes, the functions that make up an API invoke the actual system calls on behalf of the application programmer.

Benefits of using an API to make system calls:

- It adds another layer of abstraction hence simplifies the process of application development4

- Supports program portability5

Head to this appendix section if you’d like to see some examples.

Usage and Implementation

An API helps users make appropriate system calls by providing convenient wrapper functions. More often than not, we don’t need to know its detailed implementation as the API already provides convenient abstraction.

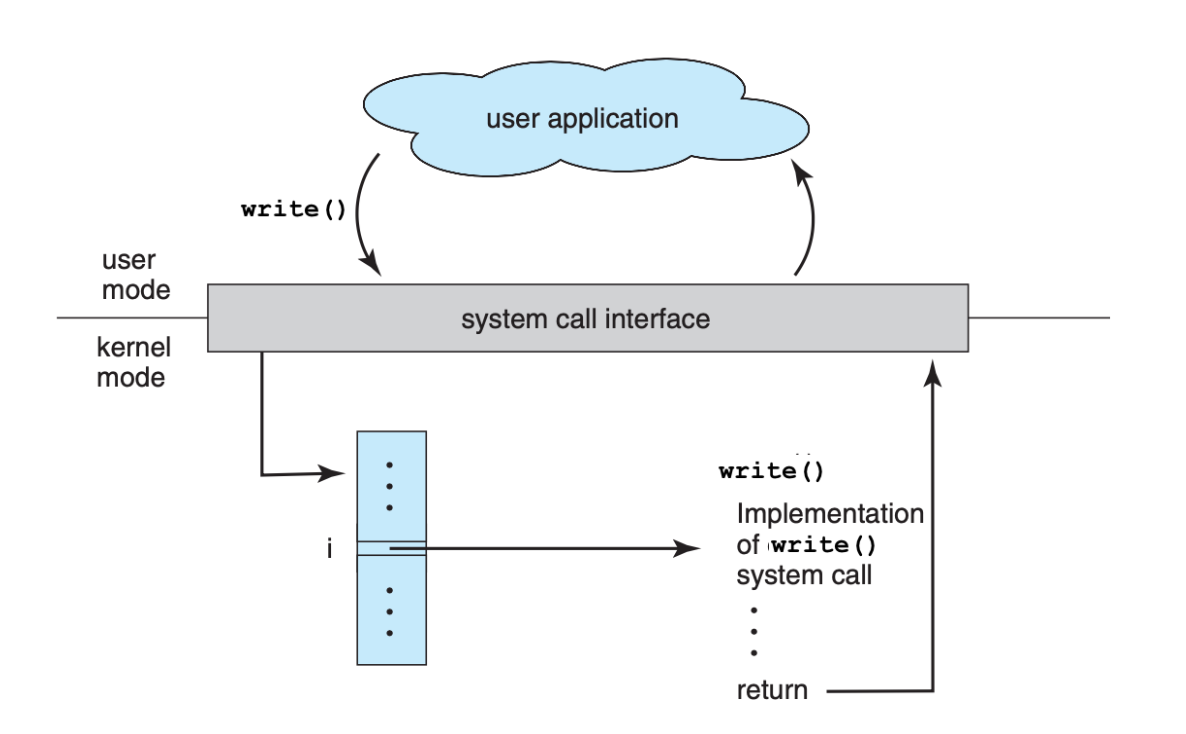

For most programming languages, the run-time support system (a set of functions built into libraries included with a compiler) provides a system call interface that serves as the link to system calls made available by the operating system. The system-call interface intercepts function calls in the API and invokes the necessary system calls within the operating system.

The exact implementation differs from system to system, head to this appendix section if you’re interested to find out more.

Hopefully after understanding this part, you won’t say stuffs like this at work:

A simple example in C

Here’s a simple example in C that demonstrates how to use a system call API in C. In this example, we’ll use the write() system call API in C to write text to the console:

#include <unistd.h> // For the write() system call

#include <string.h> // For strlen()

int main() {

const char *message = "Hello, system call!\n";

write(1, message, strlen(message)); // 1 is the file descriptor for stdout

return 0;

}

Here’s what’s happening in this example:

- Header Files: We include

unistd.hfor thewrite()system call andstring.hforstrlen()to calculate the length of the string. - Message: We define a message that we want to write to the console.

- write() System Call API: We call

write()with three arguments:1is the file descriptor for standard output (stdout). File descriptor1is universally used for stdout in Unix and Linux environments.messageis the pointer to the buffer containing the string we want to output.strlen(message)calculates the length of the string, tellingwrite()how many bytes to write.

Parameter Passing

System call service routines are just like common functions, implemented in the kernel space. They require parameters to run. For example, if we request a write, one of the most obvious parameters required are the bytes to write.

There are three general ways to pass the parameters required for system calls to the OS Kernel.

Registers

Pass parameters in registers:

- For the example of

writesystem call, Kernel examines certain special registers for bytes to print - Pros: Simple and fast access

- Cons: There might be more parameters than registers

Stack

Push parameters to the program stack:

- Pushed to the stack by process running in user mode, then invoke

syscall - In kernel mode, pops the arguments from the calling program’s stack

Block or Table

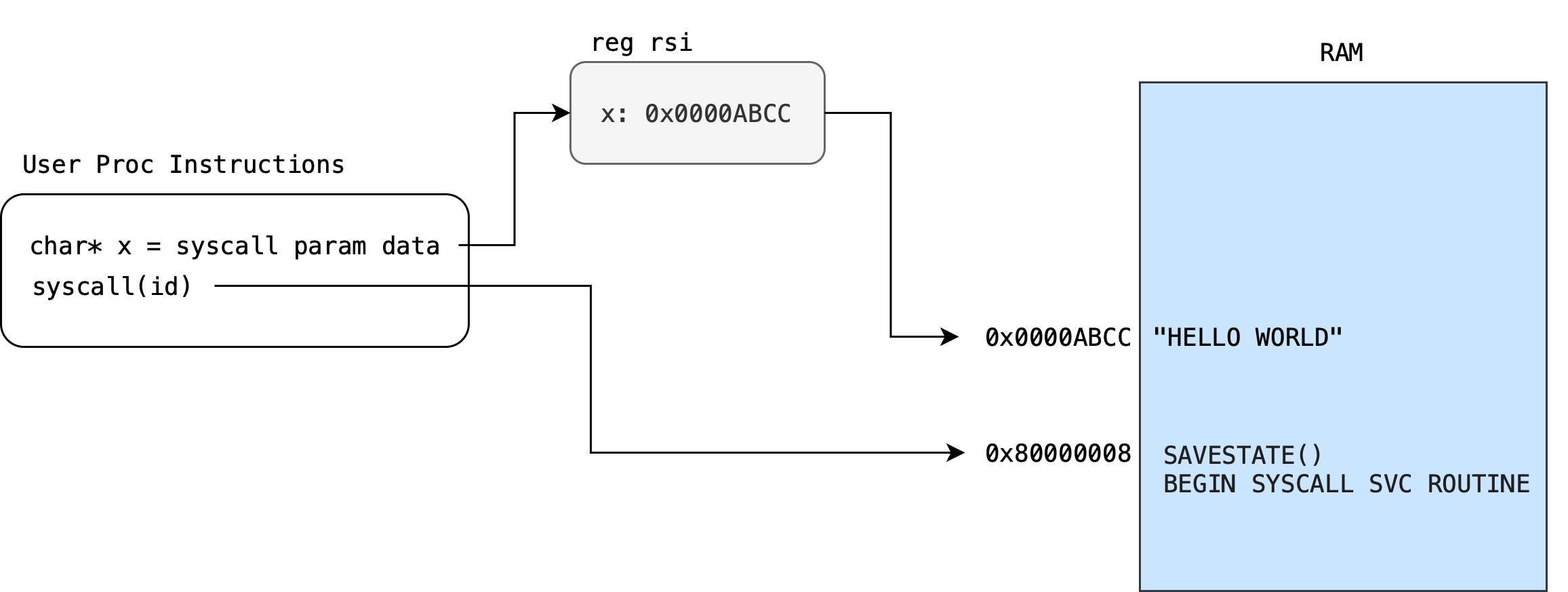

Pass parameters that are stored in a persistent contiguous location (table or block) in the RAM (this is a different location from stack!) and pass the pointer (address) through registers, to be read by the system call routine:

- As illustrated below,

xrepresents the address of the parameters for the system call. - When system call

id(e.g:write) is made, the kernel examines certain registers, in this example isrsito obtain the address to the parameter (the bytes to write tostdout) - Given the pointer, Kernel can find the parameter for the system call in the RAM, as illustrated below:

Types of System Calls

In general, each OS will provide a list of system calls that it supports. System calls can be grouped (but not limited to) roughly into six major categories:

- Process control: end, abort, load, execute, create and terminate processes, get and set process attributes, wait for time, wait for event, signal event, allocate, and free memory

- File manipulation: create, delete, rename, open, close, read, write, and reposition files, get, and set file attributes

- Device manipulation: request and release device, read from, write to, and reposition device, get and set device attributes, logically attach or detach devices

- Information maintenance: get or set time and date, get or set system data, get or set process, file, or device attributes

- Communication: create and delete pipes, send or receive packets through network, transfer status information, attach or detach remote devices, etc

- Protection: set network encryption, protocol

If you are curious about Linux-specific system call types, you can find the list here.

Blocking vs Non-Blocking System Call

A blocking system call is one that must wait until the action can be completed.

For instance, read() is blocking:

- If no input is ready, the calling process will be suspended

yield()the remaining quanta, and schedule other processes first

- It will only resume execution after some input is ready. Depending on the scheduler implementation it may either:

- Be scheduled again and retry (e.g: round robin)

- The process re-executes

read()and mayyield()again if there’s no input. - Repeat until successful.

- The process re-executes

- Not scheduled, use some

waitflag/status to tell the scheduler to not schedule this again unless some input is receivedwaitflag/status cleared by interrupt handler (more info in the next topic)

- Be scheduled again and retry (e.g: round robin)

On the other hand, a non blocking system call can return almost immediately without waiting for the I/O to complete.

For instance, select() is non-blocking.

- The

select()system call can be used to check if there is new data or not, e.g: atstdinfile descriptor. - Then a blocking system call like

read()may be used afterwards knowing that they will complete immediately.

Process Control

In this section we choose to explain one particular type of system calls: process control with a little bit more depth.

Process Abort

A running process can either terminate normally (end) or abruptly (abort). In either case, system call to abort a process is made.

If a system call is made to terminate the currently running program abnormally, or if the program runs into a problem and causes an error trap, a dump of memory (called core dump) is sometimes taken and an error message generated.

It consists of the recorded state of the program memory at that specific time when the program crashed. The dump is written to disk and may be examined by a debugger; a type of system program. It is assumed that the user will issue an appropriate command to respond to any error.

Process Load and Execute

Loading and executing a new process in the system require system calls. It is possible for a process to call upon the execution of another process, such as creating background processes, etc.

- For instance the shell creates a new process whenever it receives a new command, and requests to execute that command in the new process (next chapter)

Process Communication

Having created new jobs or processes, we may need to wait for them to finish their execution, e.g: the shell only gives the next prompt after the previous command has completed its execution.

- We may want to wait for a certain amount of time to pass

(wait time); more probably, we will want to wait for a specific event to occur(wait event). - The jobs or processes should then signal when that event has occurred

(signal event). - Also, sometimes two or more processes share data and multiple processes need to communicate (e.g: a web server communicating with the database server).

- All these features to

wait, signal event, and other means of process communication are done by making system calls since each process is run in isolation by default, operating on virtual addresses.

Examples

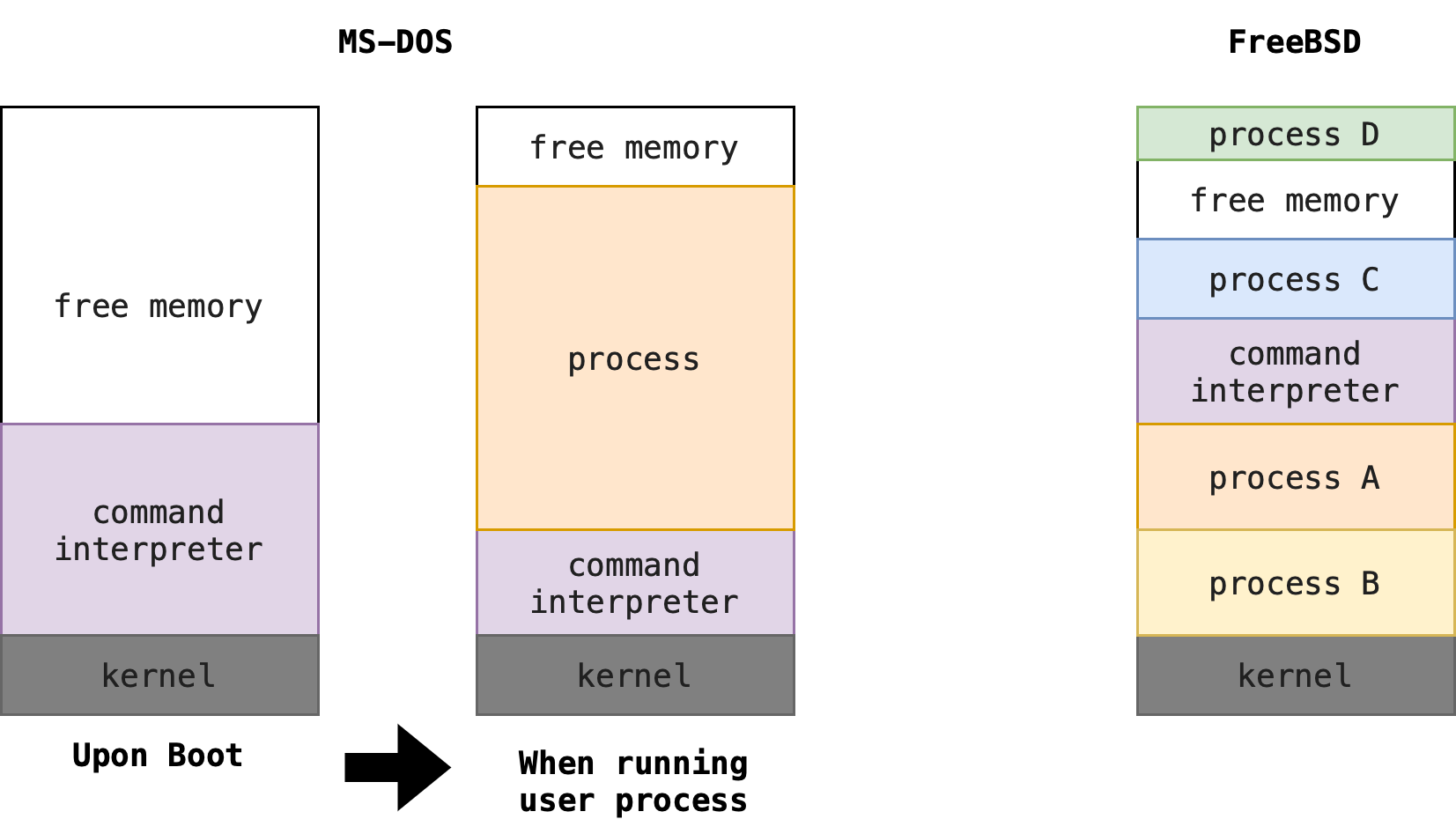

There are so many facets of and variations in process and job control that we need to clarify using examples: MS-DOS and FreeBSD.

Single-tasking System

An example of a single-tasking system is MS-DOS, shown in the figure on the left.

It has a simple command interpreter (that is invoked when the computer is started as shown in the figure above, labeled as (a)). Upon opening a new program, it loads the program into memory, writing over most of itself (note the shrinking portion of command interpreter codebase) to give the program as much memory as possible as shown in (b) above.

Next, it sets the instruction pointer to the first instruction of the program.

- The program then runs, and either an error causes a trap, or the program executes a system call to terminate.

- In either case, the error code is saved in the system memory for later use.

Following this action, the small portion of the command interpreter that was not overwritten resumes execution:

- Its first task is to reload the rest of the command interpreter from disk.

- Then the command interpreter makes the previous error code available to the user or to the next program.

- It stands by for more input command from the user.

Multi-tasking system

An example of a multi-tasking system is FreeBSD. The FreeBSD operating system is a multi-tasking OS that is able to create and manage multiple processes at a time.

When a user logs on to the system, the shell (command interpreter) of the user’s choice is run. This shell is similar to the MS-DOS shell in that it accepts commands and executes programs that the user requests.

However, since FreeBSD is a multitasking system, the command interpreter may continue running while another program is executed:

- The possible state of a RAM with FreeBSD OS is as shown in the figure above

- To start a new process, the shell executes a

fork()system call. - Then, the selected program is loaded into memory via an

exec()6 system call, and the program is executed normally until it executesexit()system call to end normally orabortsystem call.

Depending on the way the command was issued, the shell then either waits for the process to finish or runs the process “in the background”. In the latter case, the shell immediately requests another command.

The kernel is responsible to ensure that context switching is properly done (and timesharing as well if enabled).

To run a command in the background, add the ampersand symbol (&) at the end of the command:

command &

Summary

This chapter offers an in-depth examination of the services provided by operating systems to facilitate user interactions and efficient system management. It explores various aspects of system calls and user interfaces, detailing how these elements work together to enhance the functionality and user-friendliness of computing systems.

Key learning points include:

- System Calls and API: Discusses how system calls serve as interfaces for programs to request services from the OS kernel, including process control, file manipulation, and device management.

- User Interfaces: Explores the roles of graphical (GUI) and command-line interfaces (CLI) in providing access to system services, emphasizing the ease of use and functionality they offer to users.

- Process and Resource Management: Detailed explanation of how operating systems handle processes, manage resources, and ensure security through careful control and monitoring.

In summary, operating systems provide essential services that enhance user interaction and system efficiency through various interfaces and functionalities. They manage resource allocation, execute programs, facilitate I/O operations, and maintain file systems. Additionally, OS services include process communication and error detection to ensure stable and secure operations. The OS interfaces, such as the graphical user interface (GUI) and command-line interface (CLI), enable users to interact with these services effectively.

Appendix

System Call via API Examples

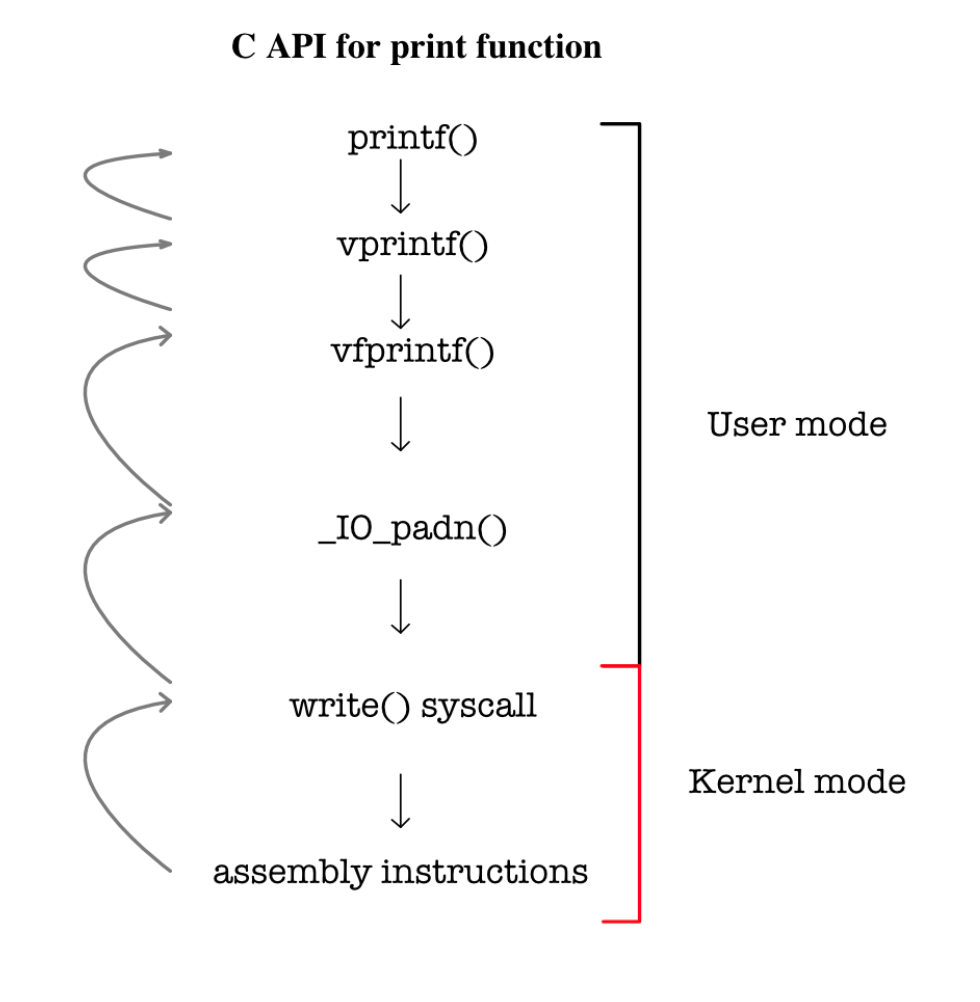

Example: printf()

We always conveniently call printf() whenever we want to display our output to the console in C. printf itself is a POSIX system call API.

- This function requires kernel service as it involves access to hardware: output display.

- The function

printfis actually making several other function calls to prepare the resources or requirements for this system call and finally make the actual system call that invokes the kernel’s help to display the output to the display.

The full implementation of printf in Mach OS can be found here. It calls other functions like putc and eventually write function that makes the system call to stdout file descriptor.

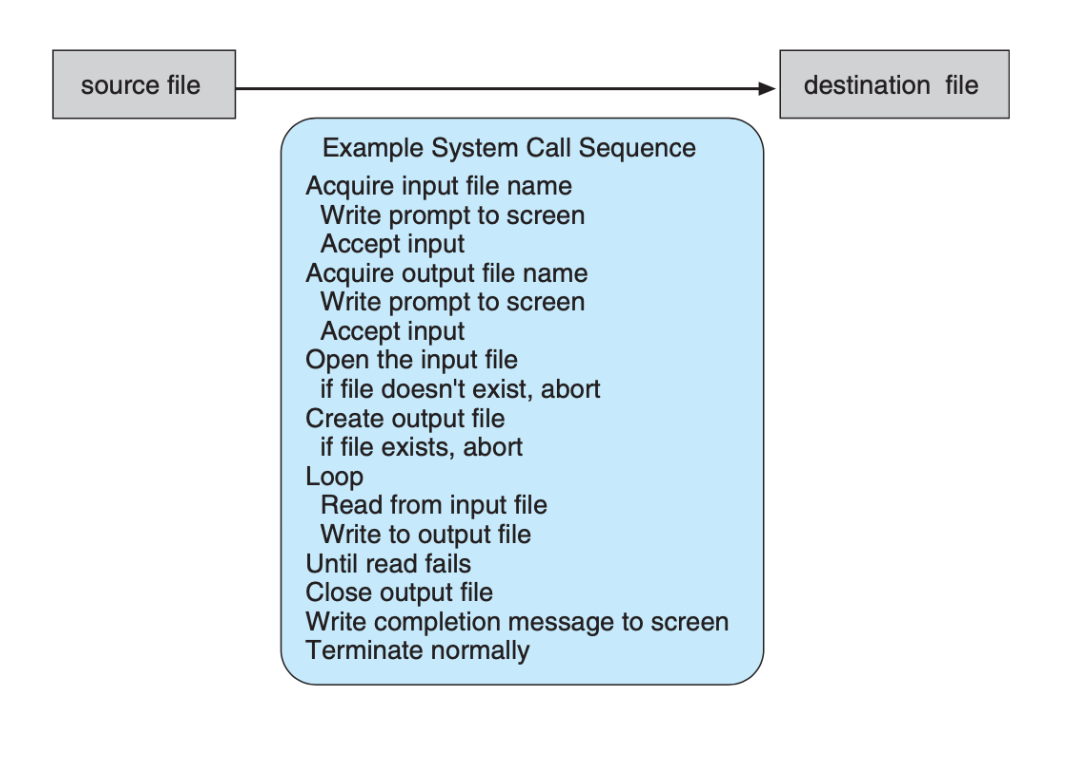

Example: CopyFile()

We also always conveniently copy one file into another location (be it programmatically or through the GUI). In Windows OS, this is supported by the CopyFile7 function (Win32 API):

CopyFile(szFilePath.c_str(), szCopyPath.c_str(), FALSE );

The complete documentation can be found here. The instruction sequence that is made by this CopyFile function to complete the entire copy operation is actually pretty lengthy, involving multiple system calls. In CopyFile case alone, multiple system calls are made for writing to file, opening files, obtaining file name, reading from file, termination, etc (image below taken from SGG book)

The actual implementation details (source code) of OS functions like CopyFile are intentionally not documented and can be changed at any time. The API however is well documented and conformed to so others who rely on it will not have their programs broken due to internal OS updates.

System Call Detailed Implementation

System calls are interfaces through which user applications interact with the operating system’s kernel to perform tasks that require higher privileges, such as I/O operations, process management, and file manipulations. Here’s a high-level overview of their implementation and the role of system call numbers:

-

System Call Implementation: System calls are implemented as part of the operating system kernel. When a user program invokes a system call, it executes a software interrupt or a special instruction that switches the processor from user mode to kernel mode. This transition is necessary because system calls often require accessing resources that are protected and can only be safely manipulated by the kernel.

-

System Call Number: Each system call is associated with a unique identifier known as a system call number. This number is used to index into a system call table maintained by the kernel, which maps numbers to the corresponding system call handlers. When a system call is invoked, the kernel uses this number to find the appropriate function to execute.

The system call mechanism is a critical component of the operating system, allowing for safe and controlled interaction between user applications and hardware or kernel functions.

System Call Number

Typically, a number is associated with each system call, and the system-call interface maintains a table indexed according to these numbers. For example, Linux system call tables and its associated numbers can be found here and FreeBSD Kernel System call table can be found here.

To further understand the points above, let’s see a sample assembly file to print Hello World to console.

Hello World in Assembly (Linux, x86-64)

; hello_world.s

global _start

section .text

_start:

mov rax, 1 ; system call number for write

mov rdi, 1 ; making file handle stdout

mov rsi, msg ; passing adress of string to output

mov rdx, msglen ; number of bytes

syscall ; invoking os to write

mov rax, 60 ; sys call number for exit

mov rdi, 0 ; exit code 0 EXIT_SUCCESS

syscall ; invoke os to exit

section .rodata

msg: db "Hello, world!", 10

msglen: equ $ - msg

Compilation and execution:

nasm -f elf64 -o hello_world.o hello_world.s

ld -o hello_world hello_world.

./hello_world

Hello World in Assembly (macOS X, x86-64)

; hello_world.s

global _main

section .text

_main:

mov rax, 0x2000004 ; system call number for write

mov rdi, 1 ; file descriptor 1 is stdout

mov rsi, msg ; get string address

mov rdx, msg.len ; number of bytes

syscall ; exec syscall write

mov rax, 0x2000001 ; syscall number for exit

mov rdi, 0 ; exit code 0

syscall ; exit program

section .data

msg: db "Hello, world!", 10

.len: equ $ - msg

Compilation and execution:

nasm -f macho64 hello_world.s

ld -lSystem -o hello_world hello_world.o

./hello_world

Hello World in Assembly (macOS X, M1)

// hello_world.s

.global _start // Provide program starting address to linker

.align 2

// Setup the parameters to print hello world

// and then call Linux to do it.

_start: mov X0, #1 // 1 = StdOut

adr X1, helloworld // string to print

mov X2, #13 // length of our string

mov X16, #4 // MacOS write system call

svc 0 // Call linux to output the string

// Setup the parameters to exit the program

// and then call Linux to do it.

mov X0, #0 // Use 0 return code

mov X16, #1 // Service command code 1 terminates this program

svc 0 // Call MacOS to terminate the program

helloworld: .ascii "hello, world!\n"

Compilation and execution:

as -g -o hello_world.o hello_world.s

ld -macosx_version_min 12.0.0 -o hello_world hello_world.o -lSystem -syslibroot `xcrun -sdk macosx --show-sdk-path` -e _start -arch arm64

./hello_world

From the three examples above, it is obvious that system call numbers are hardware dependent. Note that the registers used are also machine specific. In x86-64 architecture, rax stands for the register to pass the system call id, rdi stands the register that should contain file descriptor (1 for stdout in your terminal), etc. In M1 architecture, the equivalent to rax is X16, and rdi is X0.

Hello World in C

In contrast, here’s an implementation in C, short and sweet.

// hello_world.c

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// printf() displays the string inside quotation

printf("Hello, World!");

return 0;

}

Compilation and execution:

gcc -o hello_world hello_world.c

./hello_world

Here’s the implementation in Python. Even shorter and sweeter:

# hello_world.py

print('Hello, world!')

Execution: python hello_world.py

The same C program can be compiled for either OS, and so is the python program. The C system call interface then invokes the intended system call in the operating-system kernel by trapping itself and invoking the trap handler (runs in kernel mode from now onwards):

- The trap handler first saves the states of the process8 and examines the system call index left in a certain register.

- It then refers to the standard system call table and dispatches the system service request accordingly, i.e: branches onto the address in the Kernel space that implements the system call service routine of the system call with that index and executes it.

When the system call service routine returns to the trap handler, the program execution can be resumed. If the system call does not return yet (e.g: block system call like input()), then the scheduler may be called to schedule another process, while this process is put to wait until the requested service is available.

The relationship between application program, API, System call interface, and the kernel is shown below (image screenshot from SGG book):

Notice that printf is just a C function that will eventually calls the write C function, and will eventually invoke the write systemcall. We can also do the same thing by using write C function:

// hello_world.c

#include <unistd.h>

int main()

{

// write(fd, char*, #bytes)

write(1, "hello, world!\n", 14);

return 0;

}

For obvious reasons, printf is more convenient because we don’t have to care about arguments like “1” (file descriptor for stout) and “14” (bytes in the printed string) and having to read the manual page for your hardware to find out what these mean inside write.

write is actually a convenient and more human-friendly wrapper around the another C function: syscall. It utilises the symbol SYS_write to indicate the system call number which value varies depending on the OS.

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/syscall.h>

int main()

{

// write(fd, char*, #bytes)

syscall(SYS_write, 1, "hello, world!\n", 14);

return 0;

}

Many wrappers in APIs are named after the system call itself, just like write or syscall that’s meant to invoke the actual WRITE system call and invoke the syscall routine.

In summary, making system calls directly in the application code is possible, but more complicated and may require embedded assembly code to be used (in C and C++) as well as knowledge of the low-level binary interface for the system call operation, which may be subject to change over time and thus not be part of the application binary interface; the API is meant to abstract this away.

You can find out more about Linux9 system calls API (implemented in C) here

Kernel Space

The kernel is divided into two spaces: logical and virtual, often called lowmem and vmalloc respectively.

In lowmem, it often uses a one-to-one mapping between virtual and physical addresses (its called logical mapping). That means virtual address X is mapped to physical address X+C (where C is some constant if any). This mapping is built during boot, and is never changed.

The kernel virtual address area (vmalloc) is used for non-contiguous physical memory location, so that it is easier to allocate them.

- This allocation of process memory is dynamic and on demand.

- On each allocation, a series of locations of physical pages are found for the corresponding kernel virtual address range, and the pagetable is modified to create the mapping.

- If this is done, it might be unsuitable for DMA (Direct Memory Access).

-

The most generic sense of the term shell means any program that users employ to type commands. A shell hides the details of the underlying operating system and manages the technical details of the operating system kernel interface, which is the lowest-level, or “inner-most” component of most operating systems. ↩

-

A library is a chunk of code that implements an API. An API (application programming interface) is a term that refers to the functions/methods in a library that you can call to perform the task on your behalf (without you actually having to implement the code). As its name said, an API for a particular library, is the interface to the library. The same API can be implemented by different libraries (implementation). The underlying libraries can be updated, etc without changing the API and hence not breaking other code that utilizes the API. ↩

-

Actual system calls can often be more detailed and difficult to work with than the API available to an application programmer. ↩

-

An application programmer designing a program using an API can expect her program to compile and run on any system that supports the same API (although in reality, architectural differences often make this more difficult than it may appear) ↩

-

We will learn about these system calls in the latter weeks and in lab ↩

-

From the documentation:

syscall()is a small library function that invokes the system call whose assembly language interface has the specified number with the specified arguments.syscall()in Linux saves CPU registers before making the system call, restores the registers upon return from the system call, and stores any error code returned by the system call in errno(3) if an error occurs. ↩ -

Linux is a Unix clone written from scratch by Linus Torvalds with assistance from a loosely-knit team of hackers across the Net. It aims towards POSIX compliance. ↩

50.005 CSE

50.005 CSE