- If You Removed the Kernel

- Illegal Jump to Kernel Space

- Reimagine Boostrapping

- Why We Need Both Kernel and Drivers?

- Draw the OS Stack by Privilege

- The Curious Case of the Silent Terminal

- The Blind Printer Problem

- The Reentrant Trap

- Device Drivers and Execution Mode

50.005 Computer System Engineering

Information Systems Technology and Design

Singapore University of Technology and Design

Natalie Agus (Summer 2025)

Introduction to Operating System and Its Roles

If You Removed the Kernel

Imagine that you’re designing a machine with no kernel. User programs are copied directly from disk into RAM and executed by the CPU one after another. There’s no dedicated operating system managing the system.

- What functionalities or capabilities would be missing from this system?

- Which operations would be unsafe or outright impossible without a kernel?

- Is it possible to simulate multitasking or device access in this setup? If so, how crude or complex would the approach be?

Hints:

- Think about how access to hardware is usually controlled.

- What ensures that one program doesn’t overwrite another in memory?

- How are devices like keyboards and disks normally accessed in a system?

- How does the CPU know when to switch between programs?

Think about the metaphor used in class: the OS as a “government” or “manager.” How does this experiment demonstrate the value of central coordination? What kind of “rules” or “contracts” does the kernel enforce that user programs alone cannot?

In a machine without a kernel, the most fundamental issue is the **lack of central coordination**. Key functionalities normally managed by the kernel such as memory protection, process scheduling, system calls, and I/O management would all be missing. Each program would run with **full** access to the machine’s hardware and memory, which means there would be NO isolation between programs. One buggy or malicious program could easily overwrite another program’s data or corrupt the entire system.

Operations that involve direct access to hardware such as reading input from the keyboard, writing to disk, or sending data over the network would become extremely unsafe. There would be no standardized way to perform these actions, and no protection to ensure exclusive access. This also means that programs would be forced to implement their own device-handling logic, increasing code duplication and drastically reducing safety and portability. It will burden the developers with tedious tasks, such as writing drivers (akin to your 50.002 1D project).

Multitasking could, in theory, be simulated by having programs voluntarily give up control and transfer execution to another program. However, this approach (known as **cooperative multitasking**) would be extremely fragile, as it depends on every program behaving correctly (and you know the chances for this is near zero given that programs are made by different developers). There would be no support for preemptive scheduling, meaning a misbehaving program could freeze the entire system. Furthermore, without the ability to handle interrupts, asynchronous events (like mouse clicks or hardware responses) cannot be serviced reliably.

Ultimately, this thought experiment aim to highlight the value of the kernel as the privileged component that enforces structure, safety, and fairness. It plays a vital role in managing complexity and ensuring that the computer operates as a coordinated, reliable system rather than a chaotic collection of raw binaries fighting over shared hardware.

Illegal Jump to Kernel Space

Background: Privilege Enforcement in RISC-V

RISC-V processors run code at different privilege levels, which are enforced by the hardware. This is very much like the Beta CPU. The three common modes are:

- Machine mode (M-mode): The most privileged mode. Firmware runs here.

- Supervisor mode (S-mode): The operating system kernel runs here.

- User mode (U-mode): Normal applications run here with restricted access.

- When an application runs in User mode, it can only execute non-privileged instructions and access memory marked as user-accessible. Any attempt to execute a privileged instruction (like modifying page tables) or jump to a protected kernel address (e.g.

0x80000000) will trigger a trap (supervisor call/software interrupt).

The kernel sets up page tables to define which parts of memory are visible and accessible to each process. Kernel memory (including address ranges like 0x80000000) is typically not mapped in the user process’s address space, or is marked as inaccessible.

To safely request kernel services, user programs must use a system call. In RISC-V, this is done using the ecall instruction. This causes the CPU to trap into Supervisor mode, where it runs kernel code at a controlled entry point.

Scenario

A student writes the following instruction into a user-mode program in RISC-V Architecture:

JAL 0x80000000

They expect the program to jump directly to a kernel function located at that address. But instead, the program crashes or triggers an exception.

- Why can’t a user-mode program jump directly to a kernel address?

- How does the RISC-V hardware detect and prevent this?

- What should the program have done instead to access kernel functionality?

- What are the risks if such jumps were allowed?

Hints:

- Consider what happens when a CPU in user mode tries to access memory it doesn’t have permission to.

- Check whether

0x80000000is even mapped in a user-mode program’s address space.- Think about what

ecalldoes and what the kernel registers in stvec.- Can a program safely switch to a higher privilege level by itself?

RISC-V enforces privilege boundaries by using both CPU modes and virtual memory protection. User-mode programs are sandboxed, meaning they can only execute non-privileged instructions and access user-mapped memory. If a user program tries to jump to `0x80000000`, which is typically *reserved* for kernel code, the processor **checks** the current mode and memory permissions. Since that region is inaccessible in user mode, a trap is raised often a **page fault** or **illegal instruction exception**.

This restriction is crucial. Without it, any program could access hardware directly, corrupt the kernel, or interfere with other programs. It would be **impossible** to ensure security, stability, or fairness. Instead, programs should use the `ecall` (systemcall) instruction to request services like reading a file or allocating memory. The CPU then **switches** to supervisor mode, jumps to a predefined trap handler set by the kernel, and later resumes the user program after completing the request.

This design: separating user and kernel execution is **fundamental** to modern OS design. It ensures that the kernel remains protected and that only controlled, validated transitions are allowed into privileged code.

Reimagine Boostrapping

We know that the operating system must be loaded into memory before the CPU can run it. But here’s the paradox: the OS is a program. Programs need to be in memory to run. So what loads the operating system into memory in the first place?

Background: The Bootstrapping Paradox

When a computer is powered on, its RAM is empty, and nothing is executing. But the CPU begins running instructions immediately. To resolve this paradox, every computer is built with a small, immutable piece of code stored in ROM. This is called firmware or BIOS (Basic Input/Output System).

This firmware contains just enough logic to:

- Initialize hardware devices (like disks and memory)

- Find and load the operating system into RAM

- Transfer control to the OS kernel

- This first step is called bootstrapping, and it’s designed to break the “chicken-and-egg” cycle of needing a program to load the program.

Answer the following questions:

- Why is this called a paradox in OS design?

- What is the role of the firmware (or BIOS) in the boot process?

- What exactly does the kernel do after it gets loaded into RAM?

- What could go wrong if the boot process was tampered with or failed?

Hints

- Consider: what happens immediately after you press the power button?

- Why can’t the OS already be in RAM?

- What’s special about ROM in this context?

- Could security or stability be compromised if the boot process were modified?

The bootstrapping paradox arises from the idea that programs must already be in memory before they can run but the operating system itself is just a program. So how does it get into memory in the first place?

This problem is solved by including a small, unchangeable program in the computer’s ROM. This program, called firmware or BIOS, is **automatically** executed by the CPU at power-on. Because ROM is non-volatile and hardwired into the machine, its instructions are **always available** at startup.

The firmware performs basic hardware checks, initializes the memory controller, disk interfaces, and other essential components. Then, it looks for a secondary program called the **bootloader**, which is typically stored on disk. The bootloader is responsible for loading the operating system kernel into RAM. Once the kernel is loaded, control is handed over, and the kernel takes over full system initialization: setting up device drivers, page tables, interrupt handlers, and eventually launching system services and user programs.

If the boot process were compromised, for instance: the firmware was tampered with, or the bootloader was replaced, then it could allow attackers to gain control of the system *before* the OS even starts. That’s why modern systems use technologies like **secure boot** and **trusted boot** chains to **verify** the integrity of each step in the boot sequence. A trusted boot chain works by having **each stage** of the boot process (firmware → bootloader → OS kernel) cryptographically verify the integrity and signature of the next stage before executing it. This ensures that only code from a trusted source is allowed to run, preventing tampering or malware injection at boot time. You will understand these terms better (signature, integrity, later on when we touch on Network Security)

Why We Need Both Kernel and Drivers?

The OS kernel already has full access to the hardware. So why do we need device drivers? Couldn’t all hardware be handled directly by the kernel itself? In fact, why not just compile all drivers into the kernel?

Recap: Kernel vs Device Drivers

While the kernel is the core of the OS with unrestricted access to hardware, it delegates many hardware-specific tasks to device drivers. Device drivers are modular programs that know how to talk to specific devices like printers, graphics cards, or network adapters.

Drivers can be:

- Kernel-mode drivers: Fast, but risky. Bugs can crash the system.

- User-mode drivers: Safer, but slower. We must make frequent system calls to access hardware.

Modern OSes use a modular approach, keeping the kernel minimal and extensible, while allowing drivers to be updated or swapped without rebuilding the whole OS.

Answer the following questions:

- Why aren’t all drivers just compiled permanently into the kernel?

- What are the trade-offs between running drivers in user mode vs kernel mode?

- What could go wrong if a buggy driver runs in kernel mode?

- How does this modular approach help both developers and end users?

Hints:

- Think about how often new hardware gets released.

- Who writes the drivers? The OS vendor or the hardware manufacturer?

- What happens if a graphics driver crashes while in kernel mode?

- What is the difference between performance and fault isolation?

While the kernel could, *in theory*, include hardcoded logic for every piece of hardware, this would make it **bloated**, **rigid**, and nearly **impossible to maintain**. Instead, most operating systems separate out hardware-specific code into device drivers. These drivers act as *translators* between generic kernel services and the specific command sets required by individual devices.

There are compelling reasons for keeping drivers modular. First, hardware changes frequently. Manufacturers regularly release new models with unique requirements. Bundling every possible driver into the kernel would create a **massive**, **inflexible** binary. A modular driver model allows drivers to be added, removed, or updated independently of the kernel.

Running drivers in kernel mode allows for **high performance**, since they can directly access memory and devices without frequent privilege transitions. However, this also makes them dangerous. A buggy or malicious kernel-mode driver can **corrupt** memory, **crash** the OS, or introduce severe security vulnerabilities. In contrast, user-mode drivers are **isolated** (sandboxed). They interact with hardware indirectly through system calls, which makes them safer but slower.

The modular design: kernel + drivers strikes a **balance** between performance, safety, and maintainability. It allows the core kernel to remain stable and trusted, while still supporting a wide and evolving ecosystem of hardware. Developers can write drivers independently, and users can install or update drivers without reinstalling the OS. Most modular drivers in modern systems (like Linux `.ko` kernel modules or Windows `.sys` drivers) are still kernel-mode drivers. “Modular” simply means they can be loaded and unloaded dynamically, rather than being compiled permanently into the core kernel binary.

To maintain safety, drivers must be **digitally signed** by reputable vendors or certified authorities (e.g. Microsoft WHQL or Linux kernel maintainers). Most OSes refuse to load unsigned kernel modules by default (Windows enforces this unless you disable secure boot; Linux uses signature checks if enabled). You will understand these terms better (signed, certified, later on when we touch on Network Security).

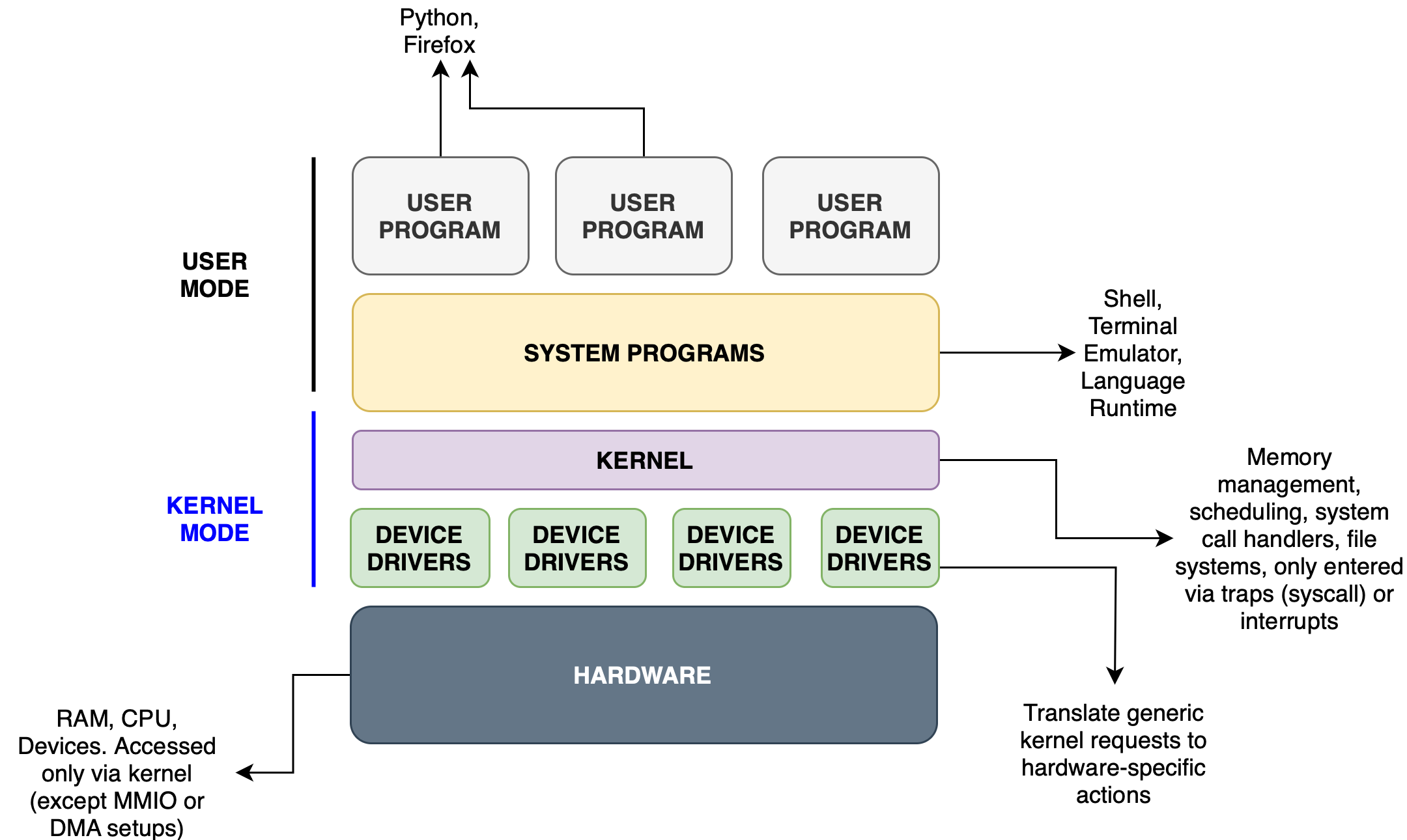

Draw the OS Stack by Privilege

You’ve now learned that different parts of the operating system run at different privilege levels (user mode and kernel mode) and that the system enforces transitions between them.

But how do these components relate in practice? Build a Visual Model.

Recap:OS Stack and Mode Switching

A modern operating system consists of layered components:

- User programs (e.g. browsers, compilers, games)

- System programs (e.g. shell, package manager, compiler runtime)

- Kernel (process manager, memory manager, scheduler)

- Device drivers (part of or loaded into the kernel)

- Hardware (CPU, RAM, disk, network, etc.)

User programs run in user mode, with limited access. The kernel and drivers run in kernel mode, with full hardware access. User programs must use system calls or traps to access hardware or OS services. They cannot jump or access kernel code directly.

Task

Draw a labeled diagram (or describe in words) that shows:

- The vertical stack of OS components, from user program to hardware

- Which layers run in user mode vs kernel mode

- How a system call transitions between modes

- How an interrupt might trigger kernel code execution

- Where drivers sit, and what privilege they require

Hints:

- Don’t forget the direction of control: who calls whom?

- What happens when a user process needs to read a file?

- What happens when a keyboard interrupt occurs?

- Where does system calls fit?

**Mode transition example:**

When a user program wants to read a file, it executes an `ecall` (in RISC-V) to request the `read()` syscall. This causes a trap: the CPU saves user state, switches to kernel mode, and jumps to the syscall handler registered in stvec. After the read is completed, the kernel uses sret to return to the user program in user mode.

**Interrupt example:**

When a device (e.g. keyboard) finishes an I/O operation, the device controller **raises** an interrupt. The CPU stops the current process, switches to kernel mode, and jumps to the interrupt handler. The kernel handles the event, possibly wakes up a waiting process, and then resumes what was previously running.

This mapping makes clear the privilege boundary, the purpose of controlled transitions, and why the OS needs both user-space flexibility and kernel-space authority.

The Curious Case of the Silent Terminal

A student writes a simple echo program in C, expecting it to read a line of input and print it back to the terminal:

#include <unistd.h>

#define BUF_SIZE 1024

int main() {

char buf[BUF_SIZE];

ssize_t n = read(0, buf, BUF_SIZE);

if (n > 0) write(1, buf, n);

return 0;

}

They compile it: gcc script.c -o a.out and run it, type a line, and press Enter.

Nothing appears. There is no output. No error. Just silence. The program exits normally.

Background: Canonical vs Raw Terminal Modes

When you type into a terminal, you’re interacting with a terminal device driver: part of the OS that manages how keyboard input is processed.

By default, terminals operate in canonical (or cooked) mode:

- Input is line-buffered. Characters will be collected until Enter is pressed.

- Special characters like backspace, Ctrl-C, and Ctrl-D are handled automatically.

- The terminal echoes every character you type back to the screen.

In contrast, raw mode disables all of that:

- Input is sent to the program immediately as each key is pressed.

- There is no line buffering and no echoing.

- The program must manually handle backspaces, Ctrl-C, and even Enter.

These behaviors are controlled by terminal flags (like ECHO and ICANON) using the termios interface. If echoing is disabled or raw mode is enabled, your program may work fine but the user sees nothing, which can look like it’s broken.

Understanding these modes is crucial when writing low-level programs that use read() and write() instead of high-level input/output libraries like printf and scanf.

Answer the following questions:

- The program uses only

read()andwrite(). Why might the terminal appear completely silent: no input shown, no output printed? - What system components are involved in this behavior? Name at least 2 things inside the OS kernel that participate.

- How does the terminal know whether or not to display typed characters?

- Suppose the user ran

stty -echo. What happens now? Can the program still work? Why or why not? - How would behavior change if the terminal were in raw mode?

Hints

- What actually causes characters to appear on screen as you type?

- Does

read()affect whether input is displayed?- Look up termios settings like

ECHOandICANON.- Try tracing with

strace ./a.out. What syscalls happen?

The program is syntactically correct and uses valid syscalls: it **reads** a line from standard input and **writes** it back. But when run, nothing appears, not even the typed input. This isn’t a bug in the code. It is a product of terminal configuration. The terminal I/O behavior we see when interacting with a program via `read()` or` write()` in Linux (or macOS) is controlled by a character device driver, specifically, **the TTY** teletypewriter subsystem driver.

By default, terminal input is handled in canonical mode, meaning input is line-buffered: characters typed are held in a buffer until `Enter` is pressed. Also, terminals usually have **echo** mode enabled, so each character is displayed as the user types it. However, if echo is disabled (e.g. by running `stty -echo`), the terminal still **collects** input and **passes** it to the program, but it doesn’t show anything on the screen as the user types. This creates the illusion that nothing is happening.

In this case, the program does receive input (after `Enter`) and writes it back. But if the shell prompt appears immediately afterward, the echoed line may visually “disappear” in the output. To confirm this, the user can try *piping* output to a file or restoring echo with `stty echo` afterward.

If the terminal is in raw mode, it gets even trickier: input is **no longer** line-buffered, `read()` may return after each character, and **additional** control keys (like backspace or Ctrl-C) no longer behave normally. The program would need to explicitly handle **byte-by-byte** input and special characters.

This scenario emphasizes how terminal I/O involves more than just system calls. It's mediated by a device driver and controlled by settings like `ICANON` and `ECHO` inside the kernel. Without understanding those, even simple programs can seem mysteriously broken.

The Blind Printer Problem

You’re designing the OS for a shared office computer connected to a single USB printer. This printer is very basic. It has no internal queue or notification system. It simply starts printing whatever it receives. Multiple user programs on the system may request to print at the same time.

You decide to make the printer interrupt-driven: when it finishes printing a page, it raises an I/O interrupt to signal readiness for the next one.

But something’s wrong. Sometimes documents get:

- Printed out of order,

- Interleaved (pages from different users mixed),

- Or overwritten halfway.

Answer the following questions:

- Why can’t multiple processes write directly to the printer, even if it uses interrupt-driven I/O?

- What role is the kernel supposed to play as a resource allocator in this scenario?

- What kind of data structure would help the kernel manage this correctly?

- Could this be solved by polling instead of interrupts? Why or why not?

- Suppose the printer had its own internal buffer. What would change?

Hints:

- Think about mutual exclusion and serialization of access.

- What happens when multiple write() calls are made to the same character device?

- Does the interrupt handler know which process sent the data?

- Would you let user programs send data directly to the device driver?

This problem illustrates a breakdown in resource allocation, specifically, the lack of exclusive access to a non-shareable, sequential device. Although the printer is interrupt-driven (which is good for efficiency), the OS must synchronize access to the printer across all processes.

The problem occurs because multiple processes are sending data concurrently to the printer device without coordination. Even though interrupts notify the kernel when the printer is ready, the kernel doesn't inherently know which process should go next, or whether previous output has finished.

As a resource allocator, the kernel should treat the printer as a **critical section**. Access must be **serialized**. This could be done using:

* A print job queue (**FIFO**) maintained in kernel space,

* Per-process spooling, where each process submits complete jobs,

* A device driver that only accepts one print job at a time and notifies the scheduler via interrupts.

Using **polling** instead of interrupts would **waste** CPU cycles (as the system would constantly check if the printer is free), and wouldn't solve the race condition unless mutual exclusion is still enforced.

If the printer had an internal buffer, the OS could offload more data at once but it still needs to serialize access, or else it would send overlapping streams from different processes.

This scenario illustrates that interrupts improve efficiency, but they do not eliminate the need for synchronization and resource management. The OS’s job isn’t just to pass signals. It must control who gets to act next.

The Reentrant Trap

You are analyzing a device driver that controls a custom serial port. The driver maintains a global buffer and exposes a write_to_device() function, which:

- Copies data into the buffer

- Starts the device transfer

- Returns immediately

You notice that sometimes, during large or repeated writes, the system crashes, or the device behaves erratically (e.g., data is sent twice, or part of it is missing). Upon inspection, you realize:

- The driver does not use any locks.

- A lock is a synchronization mechanism that ensures only one thread or process can access a shared resource or critical section at a time, preventing race conditions. You will learn more about this in the coming weeks.

- The driver is compiled with interrupts enabled.

- The device uses an interrupt handler to send the next byte when the device is ready.

Answer the following questions:

- What could go wrong if the interrupt handler calls

write_to_device()again (reentrantly) while the original call hasn’t finished? See Atomicity Assumption below. - How does preemption make the issue worse, even if the interrupt handler is simple?

- What makes a function reentrant, and is

write_to_device()reentrant in this case? - What strategies could the OS or driver use to safely handle this situation?

Atomicity Assumption

When a developer writes a simple function like

write_to_device(), they often make an implicit atomicity assumption: that the function will run from start to end without interruption. This works fine in single-threaded code. But in a multitasking OS with preemption and interrupts, that assumption breaks: the function can be paused halfway (preempted), and before it finishes, another invocation of the same function might be triggered (via an interrupt).Even though each invocation has its own stack frame, they may share globals, buffers, or device state, leading to corrupted behavior. The stack itself isn’t the problem. The problem is assuming “if I started modifying this data, no one else is touching it.” That assumption is false without explicit locking or disabling interrupts.

Hints:

- Think about what happens to shared data structures if accessed simultaneously.

- Consider call stack behavior and how preemption breaks assumptions of atomicity.

- Is it safe to modify a buffer while it’s being sent?

- What does it mean to “disable interrupts” temporarily?

The crash and erratic behavior stem from the fact that `write_to_device()` is **not reentrant**, yet it may be interrupted mid-execution, and then **called again** by the interrupt handler, leading to **race conditions** and **corruption** of shared state.

Reentrancy means a function can be **safely interrupted** and **re-invoked** before the previous call finishes. For that to work, the function must **not** use static or global variables without protection, must **avoid** modifying shared resources unless properly synchronized, must **not** depend on **execution order** or **side effects**.

In this scenario, `write_to_device()` accesses a shared buffer, possibly overwriting in-progress data or resetting internal state. If the interrupt handler re-enters it mid-way, you can get corrupted buffers, multiple concurrent transfers, lost or duplicated data.

Preemption worsens this because it introduces **unpredictability**. `write_to_device()` might get paused halfway, and then **resumed** after the interrupt handler returns, storing partial state in memory.

To prevent this, the driver should disable interrupts briefly while modifying shared structures (making it an atomic section). It can use spinlocks or mutexes to enforce mutual exclusion. It also must separate the **initiation** logic (in `write_to_device()`) from the **continuation** logic (handled exclusively by the interrupt handler). You will understand more of these terms (spinlocks, race condition, synchronization, concurrency) in the weeks to come.

This example illustrates a classic systems bug: assuming a function is safe to call anywhere, when in fact it's not reentrant and not protected from concurrency. In kernel code or drivers, these assumptions can lead to catastrophic, hard-to-debug failures.

Device Drivers and Execution Mode

Device drivers can either run in kernel mode (where they have direct access to hardware and privileged instructions) or user mode (isolated from critical system resources). Some operating systems like Linux run most drivers in kernel mode, while others like certain versions of Windows or microkernel-based systems (e.g., QNX, MINIX) allow or even require user-mode drivers.

Answer the following questions:

- Name two operating systems that run most device drivers in kernel mode, and one OS that prefers or supports user-mode drivers. You need to search the internet for answers.

- Explain three benefits of running device drivers in kernel mode.

- Explain three potential risks or drawbacks of kernel-mode drivers compared to user-mode drivers.

- Imagine you are building a new OS for a critical real-time system (e.g., a medical device). Would you place most drivers in kernel mode or user mode? Justify your choice by referring to performance, reliability, and maintainability concerns.

Two operating systems that run most device drivers in kernel mode are Linux and Windows NT-based systems (e.g., Windows 10). An operating system that supports or prefers user-mode drivers is MINIX 3, which follows a microkernel architecture. Additionally, Windows Vista and later introduced User-Mode Driver Framework (UMDF) for certain classes of devices. Running drivers in kernel mode offers **performance** benefits since drivers can directly access hardware and memory without costly user-kernel transitions. It also allows **tighter integration** with OS subsystems and avoids the overhead of inter-process communication. However, this approach has serious drawbacks. **Bugs** in kernel-mode drivers can **crash** the entire system, posing a major stability risk. It also increases the attack surface for security vulnerabilities and makes debugging more difficult due to limited tooling and lack of isolation. For a critical real-time system like a medical device, user-mode drivers should be preferred wherever possible. **Reliability** and **fault isolation** are more **important** than raw performance in such systems. A user-mode driver crash would only affect the specific device, not the whole system, and updates or debugging can be done more safely. However, for timing-critical components, kernel-mode may still be necessary if latency becomes a bottleneck. A hybrid approach (with clear justification for any kernel-mode drivers) offers the best balance between safety and performance.

50.005 CSE

50.005 CSE