- Case 1: Plain Message

- Case 2: Plain Message + IP Header

- Case 3: Plain message + IP header + “secret” password

- Case 4: Encrypted message + encrypted password + IP header

- Case 5: Signed message + Signed Nonce

- Case 6: Plain Message + Message Digest

- Case 7: Secure Email

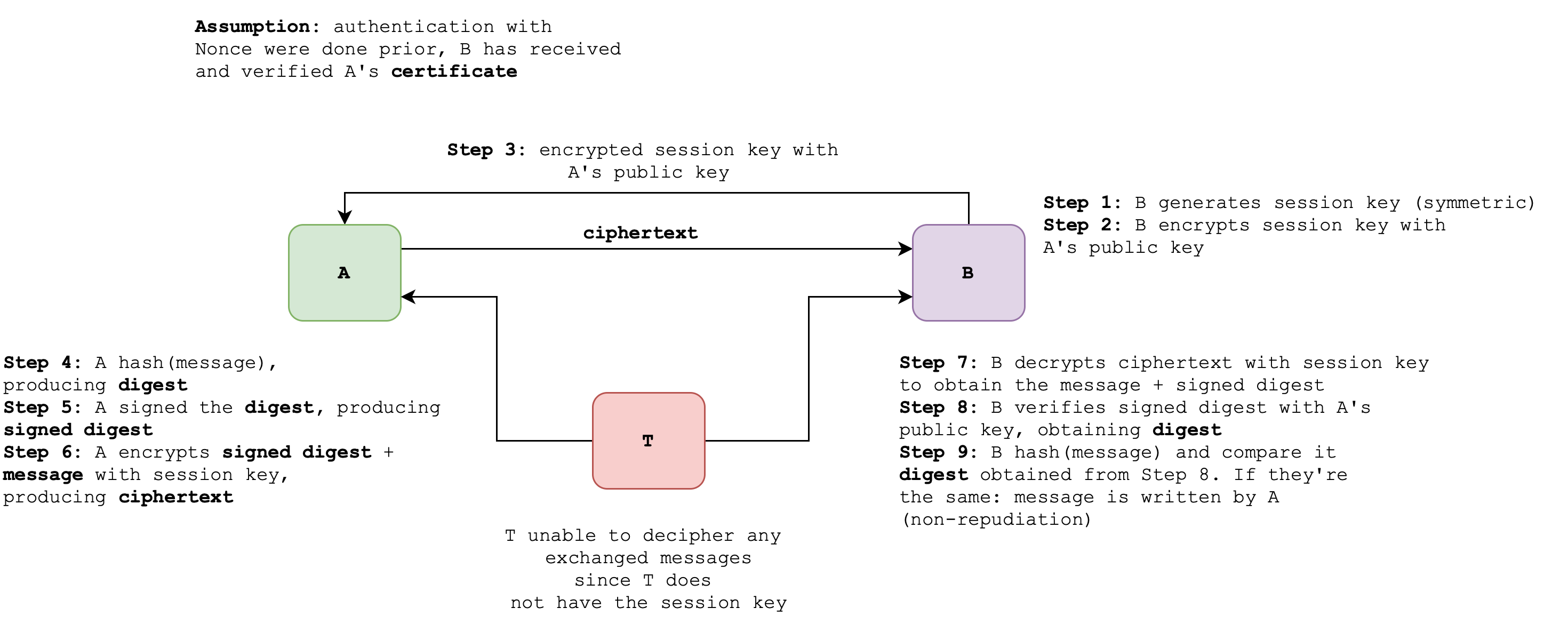

- Case 8: Secure email + non repudiation

- Summary

- Appendix

50.005 Computer System Engineering

Information Systems Technology and Design

Singapore University of Technology and Design

Natalie Agus (Summer 2025)

Application Scenarios of Cryptography

Detailed learning objectives

- List out Various Security Threats

- Explain the definition and differences between various attacks: MITM, eavesdropping, spoofing, DDoS, etc

- Name Security Risks in Plain Message Communication

- Identify how unauthenticated communication leaves systems vulnerable to spoofing and impersonation.

- Identify the impact of compromised confidentiality, integrity, and authentication.

- Evaluate the Effectiveness of Cryptography Applications

- Justify the benefits and limitations of symmetric encryption for confidentiality.

- Explain the term liveness

- Recognize how asymmetric encryption with nonce exchange helps prevent replay attacks and maintain Liveness.

- Examine the Role of Certificate Authorities (CA)

- Explain how CAs ensure secure communication through digital certificates.

- Justify how to distinguish legitimate public keys using CA-issued certificates.

- Implement Message Digests and Non-Repudiation Techniques

- Identify how hash functions ensure data integrity in secure communications.

- Explain how digital signatures guarantee non-repudiation.

- Utilize Efficient Secure Communication Techniques

- Justify how session keys facilitate secure communication without compromising efficiency.

- Explain the Explain needed to achieve non-repudiation with session keys.

- Apply Concepts to Real-World Scenarios

- Assess potential vulnerabilities in secure email communication.

- Justify the importance of verifying data integrity over confidentiality in software downloads.

These learning objectives are designed to deepen your understanding of the nuances involved in network security application scenarios, particularly focusing on how cryptography impacts confidentiality, integrity, and authentication.

Previously, we list out four security properties that are essential for secure communication over the network:

- Confidentiality

- Integrity

- Authentication

- Access and Availability

In this section, we are going to learn how cryptography can be applied to provide for property 1-3. To provide for access and availability, cryptography alone will be unable to prevent attacks that cripples access and availability. We need other algorithms, such as DNS caching to prevent DDoS attack to provide for access and availability in our system. We will learn about this in the next chapter.

For each of the cases described below, consider two end hosts, A and B who would like to communicate via the internet, and another T, who is a malicious intruder.

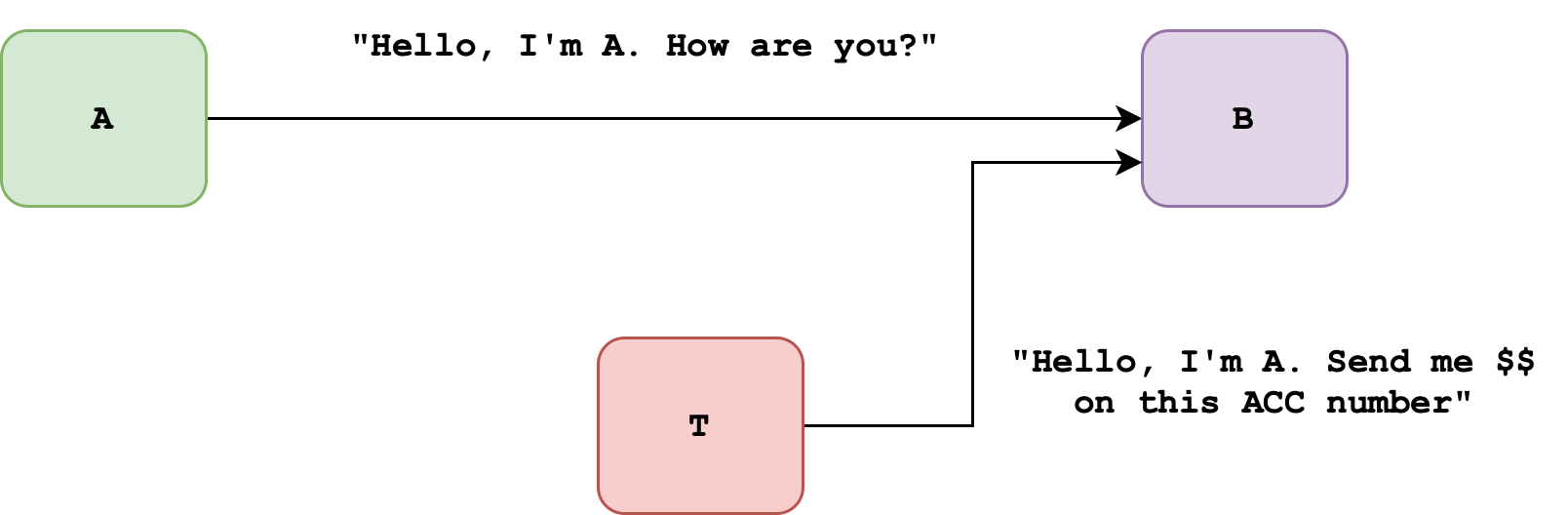

Case 1: Plain Message

Suppose A would like to communicate with B via the internet. Without any cryptography features, an intruder T can send a fake message to B (claiming that it’s sent by A). There’s no way B can differentiate whether the message comes from T or the intended host A:

- Authentication is compromised

- Integrity is also compromised

- Confidentiality is also breached

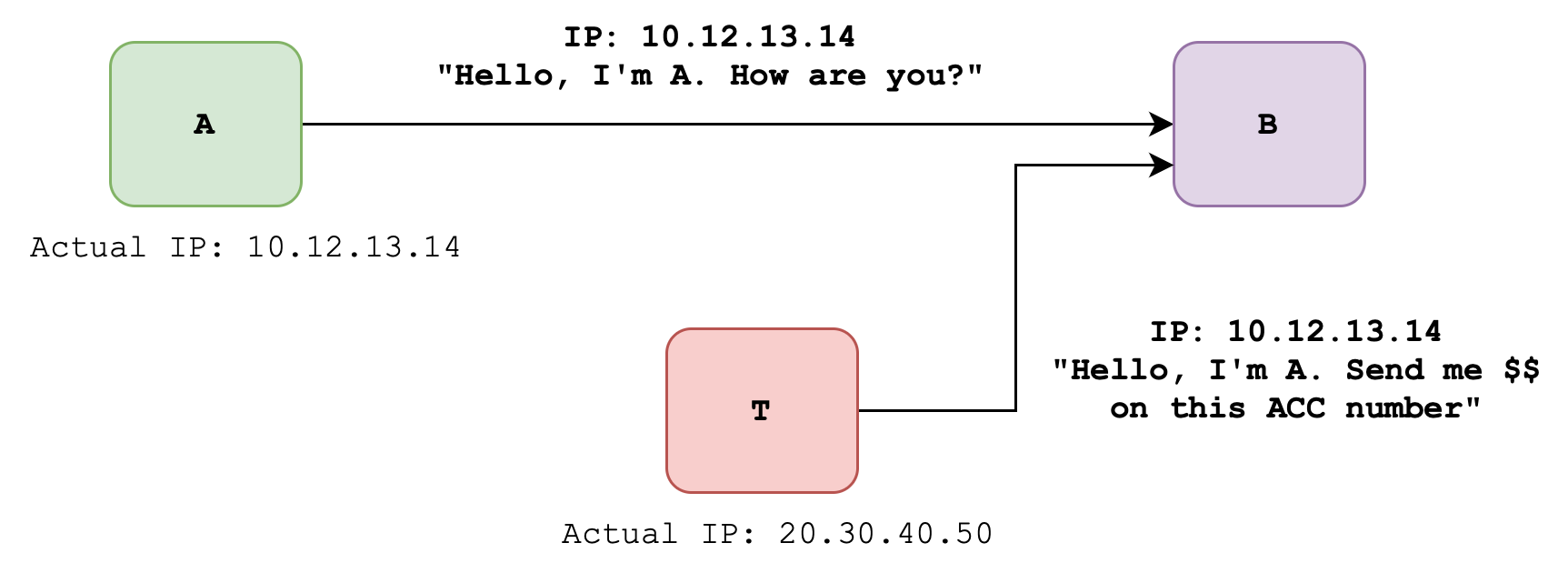

Case 2: Plain Message + IP Header

In an attempt to prove A’s identity, A will send a message to B along with their IP. However without any encryption T knows A’s IP and will be able to craft a message with A’s IP and send it to B. B won’t be able to differentiate whether the message comes from T or A:

- Authentication is compromised

- Integrity is also compromised

- Confidentiality is also breached

Spoofing

Faking one’s IP address like what T has done here is called spoofing. It’s very simple to do. Head to appendix to see a simple example using Python.

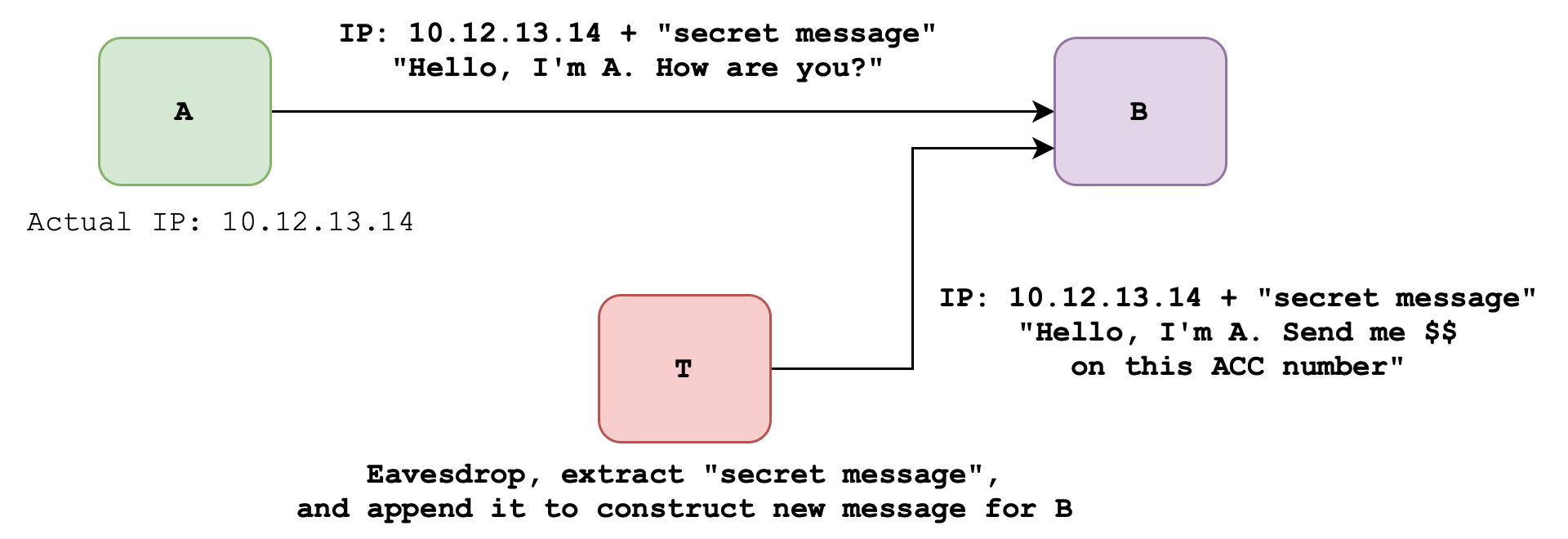

Case 3: Plain message + IP header + “secret” password

In yet another attempt to prove A’s identity, suppose A and B both share a secret codeword. A sends their IP + the secret codeword + message to B. Unfortunately, there’s nothing secret on the internet. An intruder T may eavesdrop on the conversation.

Eavesdrop Attack

This attack involves eavesdropping the messages exchanged between A and B and use the information for malicious intent.

T can echo back A’s IP + A’s “secret” password to B, but with a new message that does not come from A. Similarly, B cannot differentiate whether the message comes from A or T. Hence still without any form of encryption:

- Authentication is compromised

- Integrity is also compromised

- Confidentiality is also breached

To perform an eavesdrop attack, the attacker T does not even need to be in the same network. If the attacker is on the same local network as the target, it’s easier to perform packet sniffing because the attacker can directly intercept network traffic passing through the local network segment. This could be done by connecting to the same Wi-Fi network, being physically connected to the same Ethernet switch, or being on the same subnet. While being on the same network can simplify eavesdropping attacks, attackers can still intercept communication remotely by targeting specific network nodes or exploiting vulnerabilities in network infrastructure. Head to appendix if you’d like concreate examples on how eavesdropping is done.

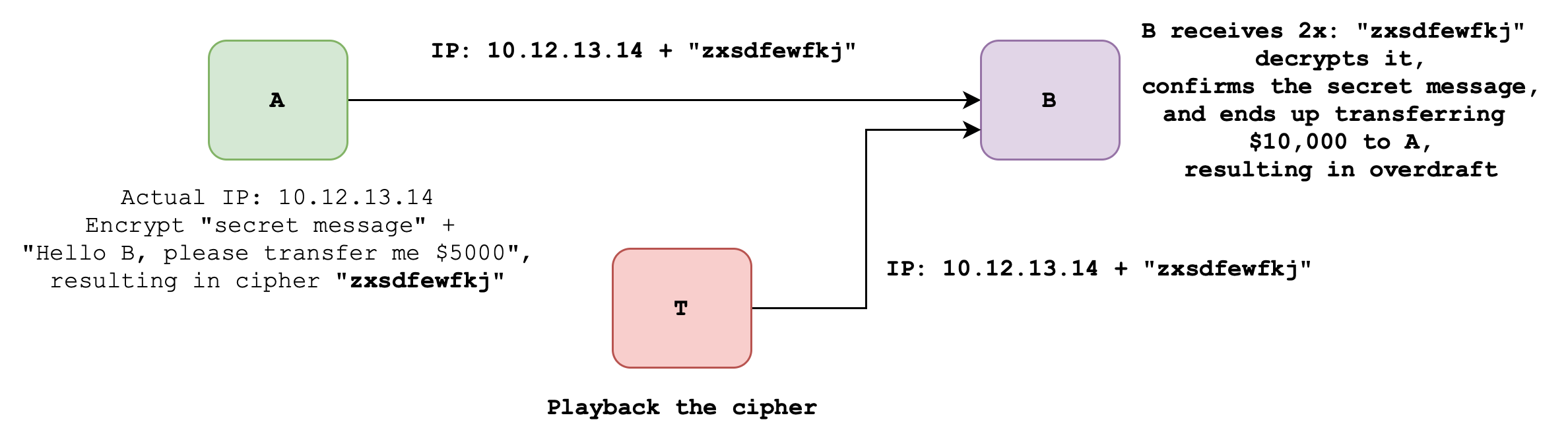

Case 4: Encrypted message + encrypted password + IP header

In this scenario, Symmetric Key Cryptography is used since it’s faster than Asymmetric Key Cryptography.

Now suppose both the message and “secret message” between A and B are now encrypted using symmetric key cryptography, such as 3DES. Even though now T cannot tell what the “secret message” between A and B is, nor can it read the content of the message. However, they can just record and replay or playback the cipher to B. This is called the replay/playback attack.

B is still not able tell if the incoming message + encrypted secret message comes from A or the intruder T. In this particular example, T does not get an extra $5000, but they damage B by incurring financial loss. The unauthorized duplicate transaction can disrupt legitimate financial transactions, cause financial losses for customers, and erode trust in the banking system and institutions involved.

Playback/replay vs eavesdropping attack

Both replay attacks and eavesdropping attacks involve intercepting network communication.

Replay attacks involve intercepting and later re-transmitting captured network data to impersonate a legitimate user, while eavesdropping attacks involve passive interception of communication to extract sensitive information without altering it.

Replay attacks aim to deceive the target system by replaying captured data, whereas eavesdropping attacks focus on listening in on communication to extract confidential information.

Therefore in Case 4:

- Authentication is not present (due to replay/playback attack)

- Integrity is present: we know that A wrote the message at some point in time because only A has the symmetric key, just that it might not be right now (not live)

- Confidentiality is present: T cannot decipher the message, only replay it

Message Integrity w/o Authentication?

Even if the message integrity is intact (in the case of replay attack), without authentication (signing of the message), there’s no way to verify the timeliness or origin of the message (origin != author). The significance of message integrity without authentication does depend on the context of the message. An attacker can replay an old message, and while its content has not been altered (thus maintaining integrity), it could still cause undesirable effects because the recepient cannot distinguish it from a legitimate, authenticated message from the author.

For critical actions publication of software update, ensuring both integrity and authentication is essential to prevent that the software being installed indeed is published from reputable source (and not some malicious software).

However, integrity without authentication for non-critical message like weather update might be sufficient as the information is used for general awareness rather than critical decision making.

Message Integrity with Authentication but without Liveness?

In some scenarios that require immediate critical decision making, liveness is also an important requirement on top of both message integrity and authentication. For time-sensitive critical actions like transferring money and a live-voting system, ensuring integrity, authentication, and liveness is essential to prevent replay attacks and unauthorized duplicated actions.

It should be clear that the above examples of time-sensitive, critical decision-making scenarios (bank transfer, voting system) are different from the software update and weather update scenarios aforementioned.

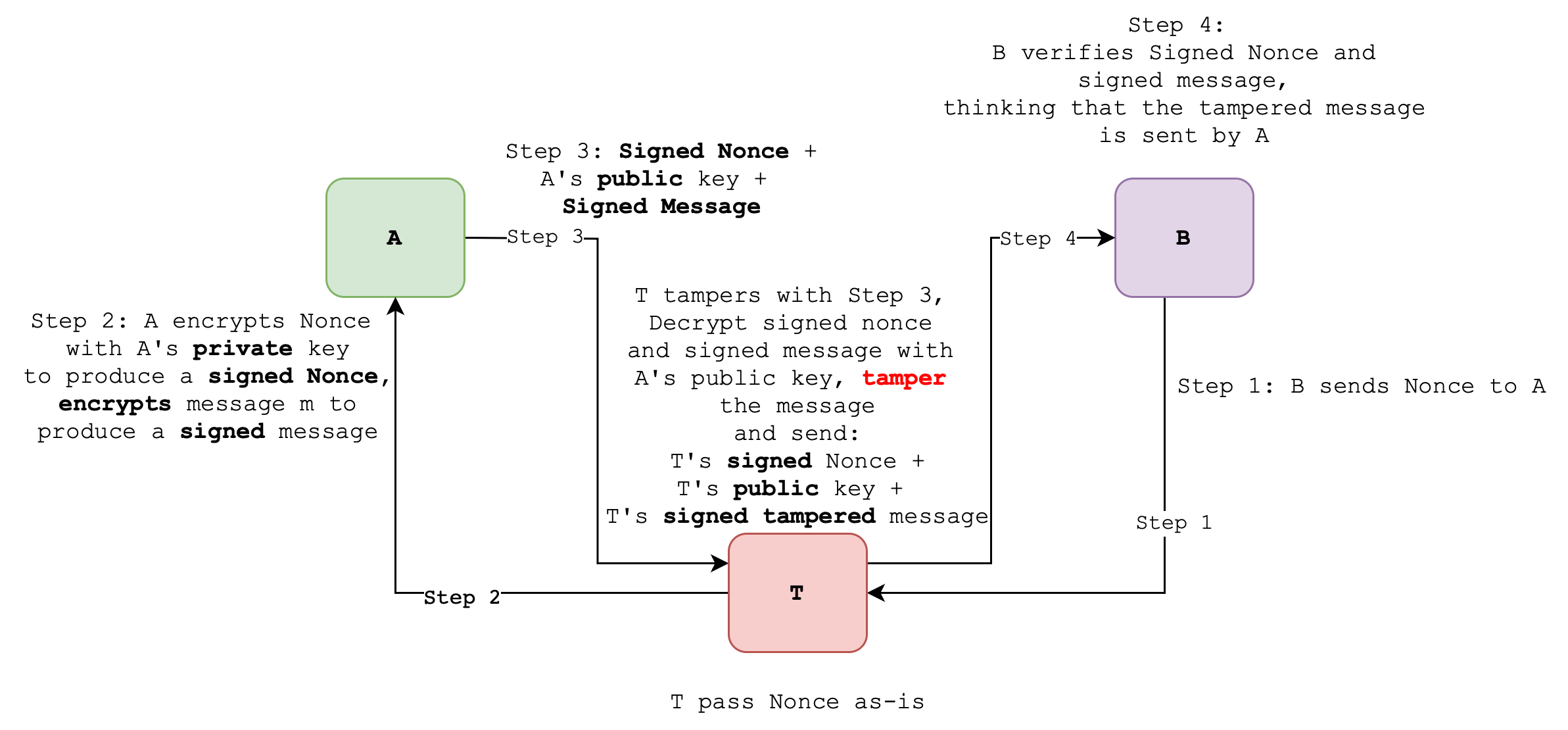

Case 5: Signed message + Signed Nonce

In this scenario, Asymmetric Key Cryptography is used. Assume that confidentiality is not a requiremement (not critical)

Case 4’s issue is that it is susceptible to replay attack. To tackle this issue, B wants to authenticate A and ensure the liveness of A. That is, if A sends the message “Transfer me $5000”, B wants to make sure that it is indeed coming from A right now.

Nonce

To do this, host A should digitally sign (encrypts with a private key) a 1-time generated number called Nonce (Number used only once).

The scenario goes as follows:

- A generates a public-private key pair

- B would like to authenticate A (make sure that A is A), and so B sends Nonce N to A

- Note: B to authenticate A, NOT the other way around

- When B authenticates A, B is sure that A is live (and B is not communicating with some replayed / stale message)

- A then encrypts Nonce with their private key, producing a signed nonce

- A also encrypts the message with their private key, producing a signed message

- Then A sends the signed nonce along with A’s public key to B + signed message

- B verifies the Nonce using A’s public key, and check that it is indeed the Nonce N sent to A previously

- This confirms that the message is fresh (not a replay message)

- B decrypts the signed message and acts upon it.

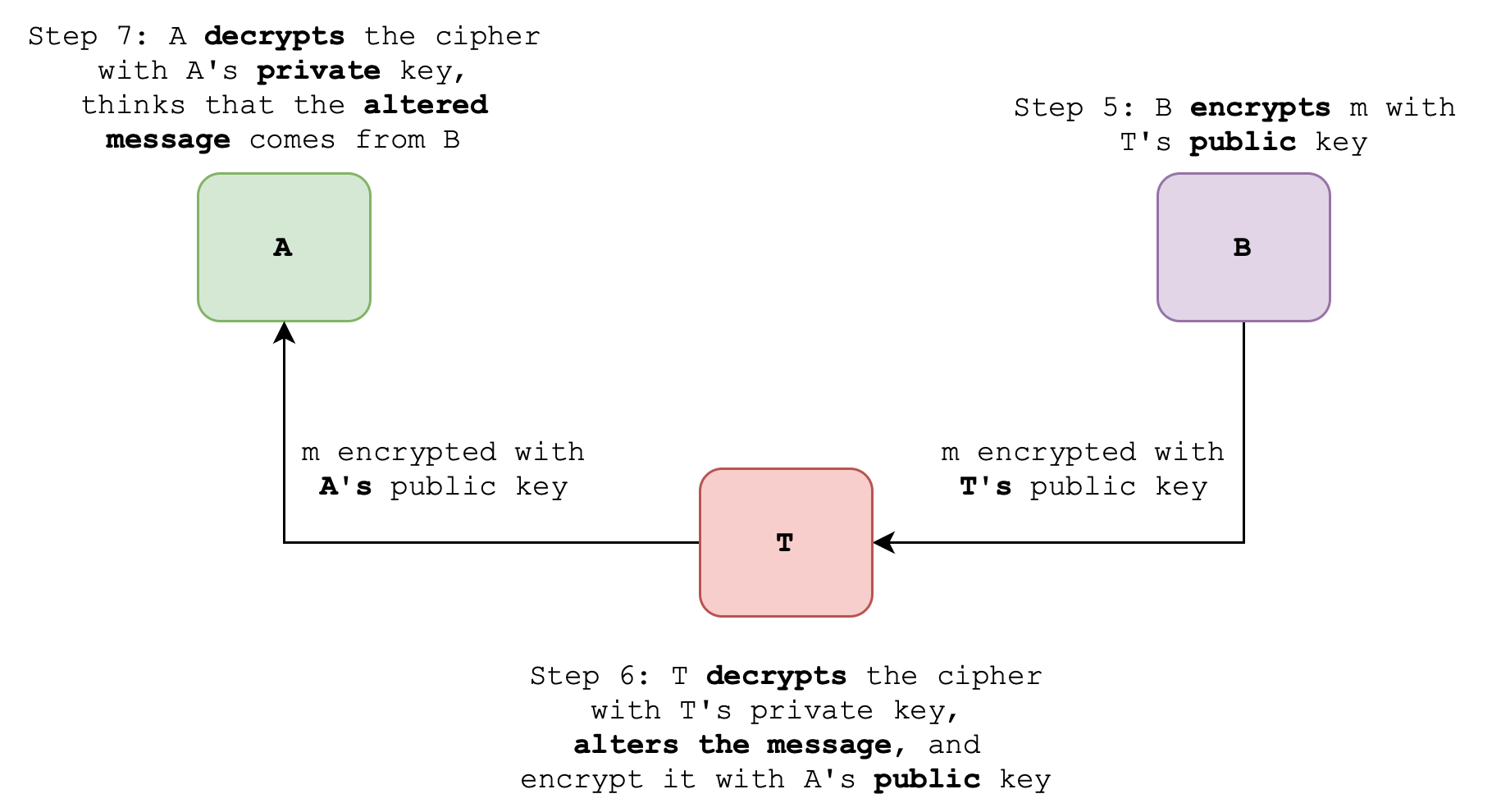

- B may send confidential message to A encrypting the reply message m with A’s public key. This way, only A can decipher the message.

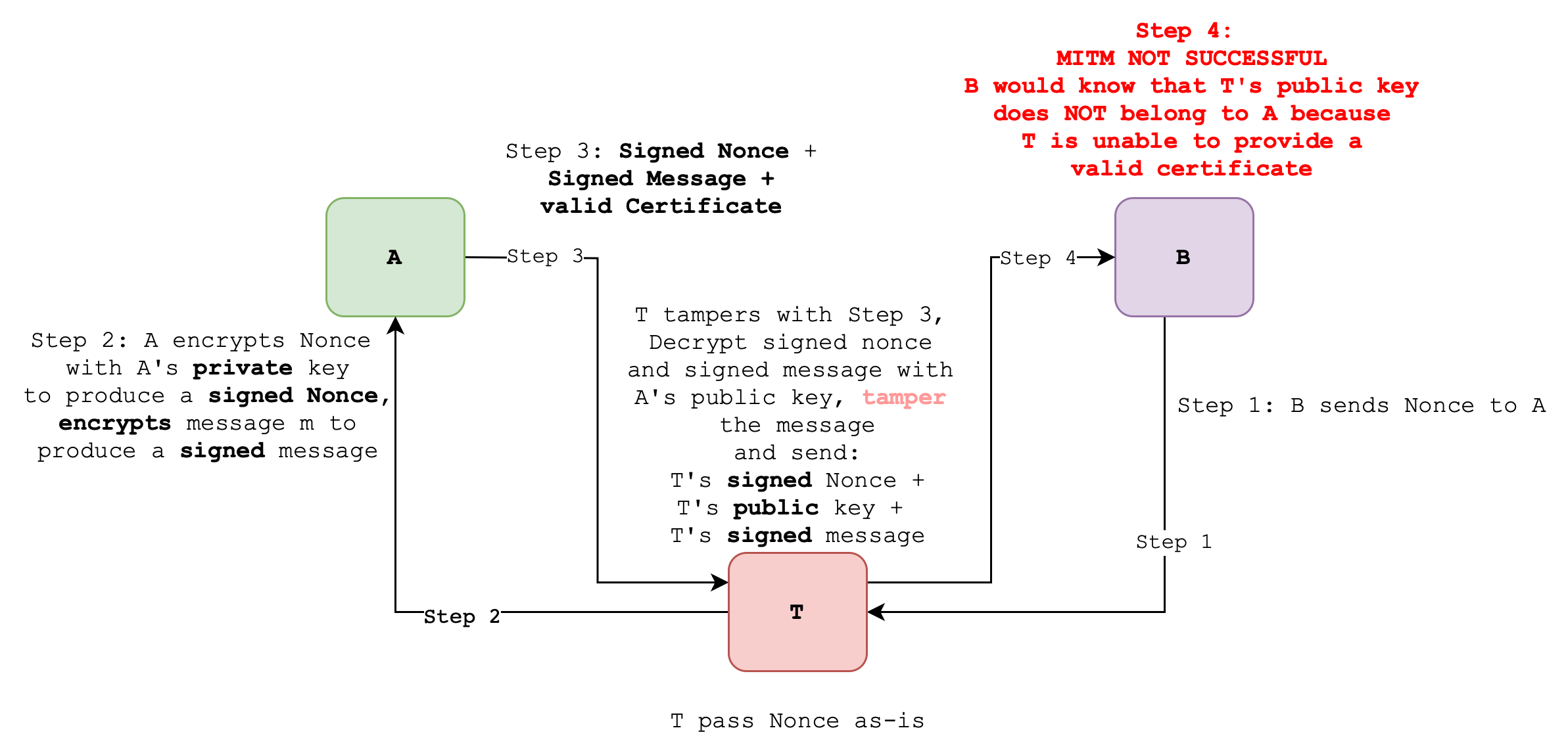

There’s still one issue with this: there’s no way that B can tell that the public key belongs to A. This is susceptible to the man-in-the-middle attack (MITM). In other words, T is able to hijack the conversation between A and B:

B’s intended “confidential” message to A is also susceptible to MITM:

Man in the middle attack

In a Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attack, an adversary intercepts communication between two parties, allowing them to eavesdrop on or manipulate the exchanged data. By impersonating one or both parties, the attacker can capture sensitive information and potentially alter the communication without detection.

Therefore in current Case 5:

- Authentication is not present: B does not know that A’s public key belong to A

- Integrity is not present: MITM attack allows T to pose as A to B and as B to A and tamper with the message exchanged

- Confidentiality is not present: same reason as above

There are two solutions to avoid the MITM attack: to utilise symmmetric key cryptography or to rely on Certificate Authority.

Utilise Symmetric Key Cryptography

This scenario can also be modified using symmetric key cryptography. Host A will encrypt the Nonce using a pre-established “shared key”. Upon receiving the message encrypted by a symmetric key that B knows only A has, B can confirm (to himself) that A wrote the message.

T can no longer hijack the conversation because simply it does not have the symmetric key. However, this solution requires A and B to both meet and share the key in person, so it is not exactly an ideal solution.

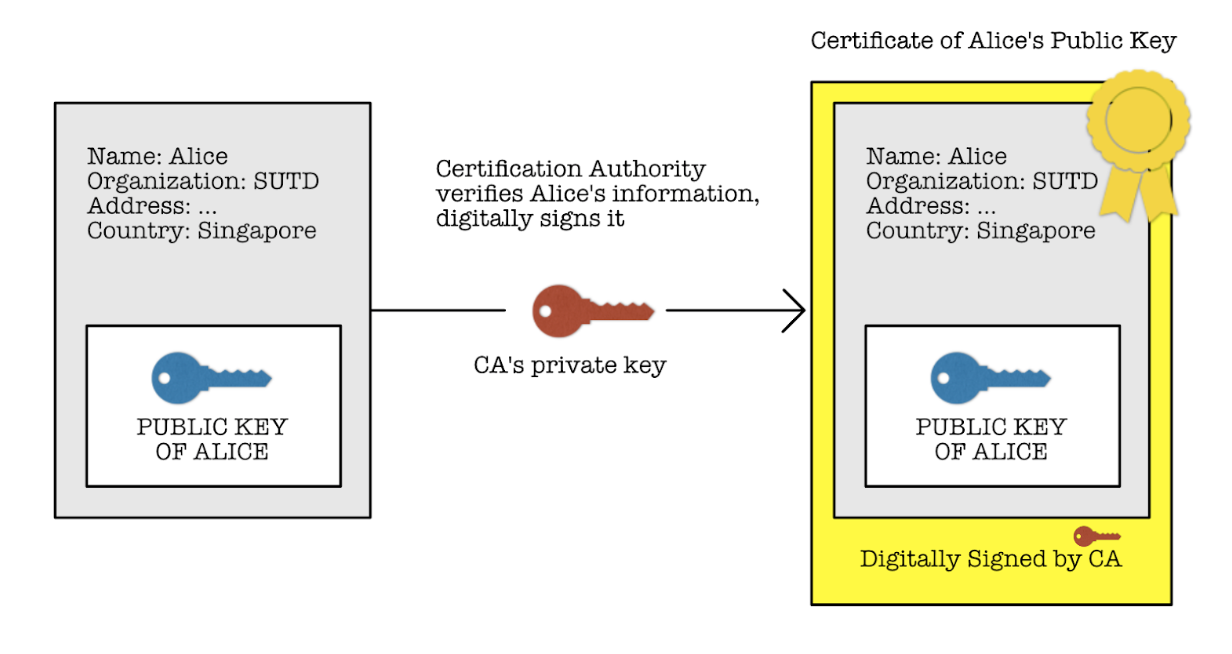

Certificate Authority

A Certificate Authority (CA) is a trusted entity responsible for issuing digital certificates that verify the identities of individuals, organizations, or devices on the internet. These certificates bind cryptographic keys to entities, ensuring secure communication through protocols like SSL/TLS by validating the authenticity of parties and enabling encrypted data exchange.

The steps goes as follows:

- A has to obtain a certificate from trusted CA

- As shown in the figure above, a certificate contains: public key, identity information, issuer information, validity period, and more

- Refer to Appendix if you’d like to find out more

- CA verifies that A exists, checks A’s documents etc

- CA issues a certificate that the Public Key of A indeed belongs to A

- This certificate is signed by CA’s private key

- CA’s public key is widely known, so we trust that nobody can impersonate the CA

- B can obtain A’s public key from the certificate by decrypting it using the CA’s widely known public key

How is CA’s public key widely known?

CA’s certificates (also known as Root certificates) containing CA’s public key are typically pre-installed with both web browsers and operating systems, providing users with a trusted foundation for validating SSL/TLS certificates during secure internet communication. This inclusion ensures that users can securely access websites and services without needing to manually manage trust settings.

The client (e.g., web browser) verifies the SSL/TLS certificate’s validity by checking if it’s signed by a trusted root certificate. If the certificate chain can be traced back to a root certificate stored in the client’s trust store, the certificate is considered valid.

This analogous to us trusting government-issued ID.

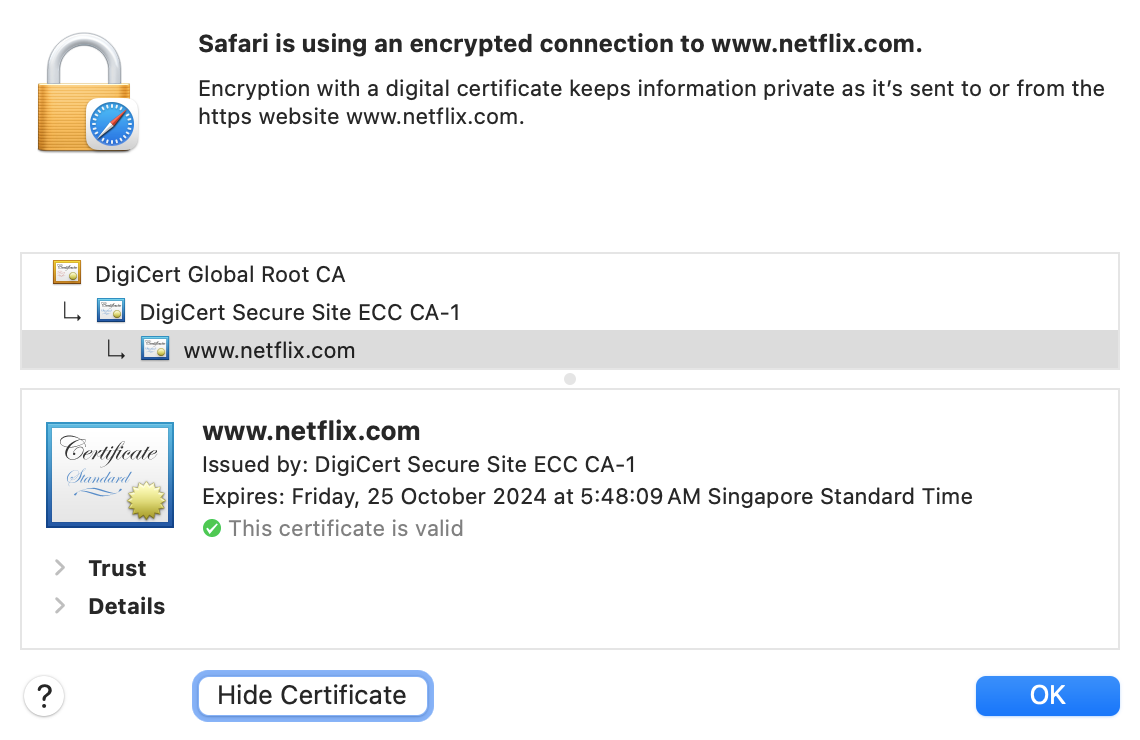

To this end, A CA obviously has to be a trusted entity such as: government (e.g., IDA) or well known provider. Real-life examples of trusted CAs are: IdenTrust, Comodo, GlobalSign, DigiCert, GoDaddy, and many more. Modern browsers will warn you if some website’s certificates are not verified. Below is an example of a legal certificate of netflix.com’s public key, signed by DigiCert as its CA.

On the other hand, below is an example of non-trusted certificate:

Let’s now review Case 5 again with the addition of CA:

The addition of a CA enables B to be sure that A’s public key indeed belongs to A. However it is still forcing A or B to encrypt messages with asymmetric key cryptography which is slow and takes up resources because it is computationally expensive. This improved Case 5 with a presence of a trusted CA nonetheless provides:

- Authentication: The Nonce ensures the message signed and sent by A is fresh. In other words, B authenticates A and ensures the liveness of A. The messages B received from A comes from A right now.

- Confidentiality: From B to A only, not the other way around.

- This is because only A has CA-signed certificate. By encrypting messages using A’s verified public key, B ensures that only A can read the message.

- If A would like to send a confidential message to B, then B needs to obtain CA-signed certificate too. A can then encrypt the message using B’s verified public key.

- Integrity: A has a CA signed certificate, hence B can verify that the signed message was authorized by A without alteration.

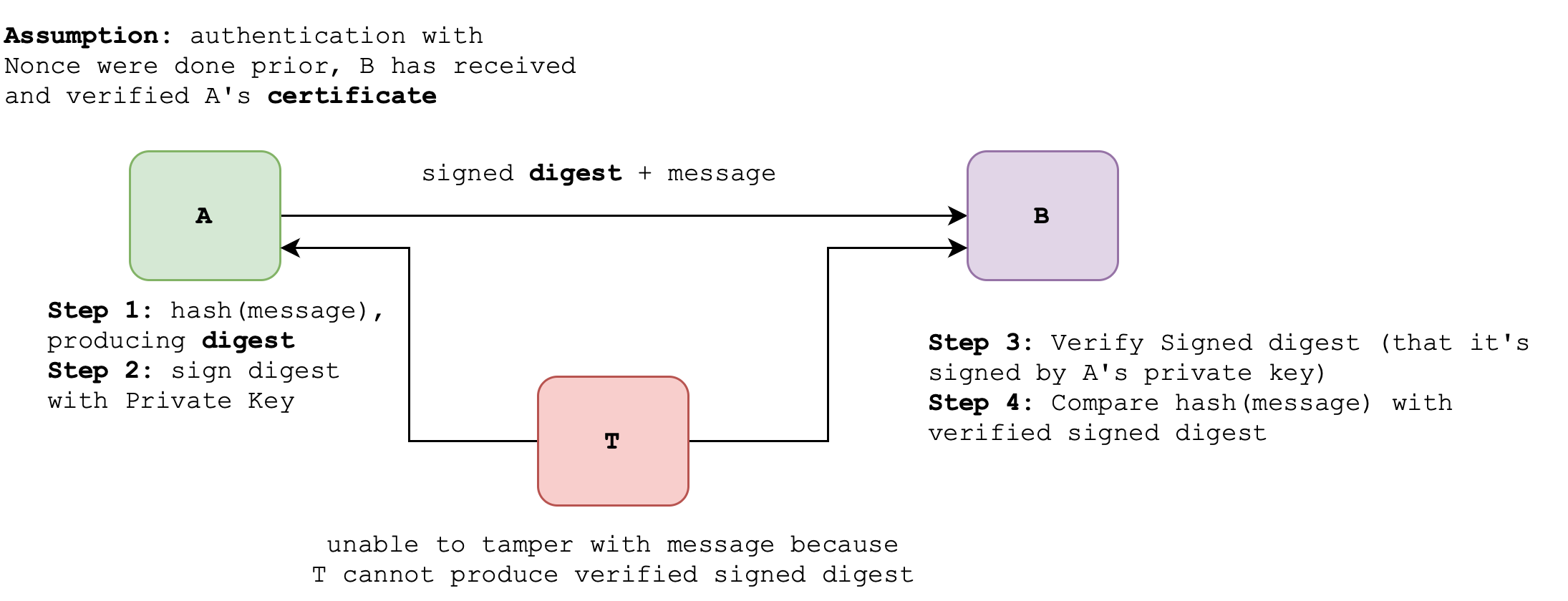

Case 6: Plain Message + Message Digest

In Case 5, we signed the whole message using A’s private key to prove integrity, and we utilise Nonce (sent by B to A) so that B can authenticate A when A sign the Nonce. However recall that public-key encryption is costly, especially if the message is very large.

Message Digest

Message digest

A message digest, also known as a hash value or hash code, is a fixed-size alphanumeric string generated by applying a mathematical function (hash function) to an arbitrary amount of data. The purpose of a message digest is to uniquely represent the input data. Even a tiny change in the input data should result in a significantly different digest.

Message digests are commonly used in various security applications such as data integrity verification, digital signatures, and password storage. Popular hash functions include MD5, SHA-1, SHA-256, and SHA-3. However, due to vulnerabilities found in some older hash functions like MD5 and SHA-1, it’s recommended to use stronger algorithms like SHA-256 for security-sensitive applications.

These hash functions are of course publicly known, but it is a convenient and efficient way to transform long messages into fixed-length messages: small enough such that we can encrypt them using A’s private key without taking too much time.

We assume that Nonce and A’s CA-issued certificate verification were done beforehand (to establish authentication, where B authenticates A). Also, note that both A and B must use the same hash function. This can either be agreed a-priori, or specified in A’s CA issued certificate. Read this appendix section to find out more.

To clarify, A sends the following after authentication is completed:

- Hashed message, encrypted with A’s private key

- Plain message (if confidentiality is not an issue)

B then confirms the integrity of the message:

- Hash the plaintext message

- Decrypt the encrypted hash sends by A using A’s public key

- Compare between (1) and (2) to ensure that A indeed sends the message

Therefore in Case 6:

- Authentication is present: We assume that nonce exchange as per Case 5 is already done and that A has CA-signed certificate

- Integrity is present: The signed message digest by A provides non-repudiation that the message was indeed written by A and not altered by any other party

- Confidentiality is not required: Since A sends the message to B in plain text, T can freely read the message.

Confidentiality is not always a security requirement, as it depends on the nature of the information being transmitted and the specific needs of the system or application. In some cases, confidentiality may not be a priority or may even be unnecessary, but integrity is necessary.

Real-life scenario: Installer Download

A scenario where integrity is critical but not confidentiality could be when downloading software updates from a trusted source, such as Microsoft official site. Imagine you’re downloading an update for your operating system directly from Microsoft’s official website. In this scenario:

-

Integrity: Ensuring the integrity of the downloaded file is crucial. You want to be certain that the file hasn’t been tampered with or altered in any way during transit. If the file’s integrity is compromised, it could potentially contain malware, viruses, or other harmful code that could compromise the security and stability of your system.

-

Confidentiality: Confidentiality is not important in this scenario as the installer is meant to be downloaded by any Windows user. This is unlike sensitive personal or financial information that you would like to download from a Banking site. In the Microsoft installer case, a long as the update process is transparent and the integrity of the update is guaranteed, the confidentiality of the update contents is not a primary concern.

By verifying the integrity of the file, you can trust that it hasn’t been tampered with and that it comes directly from the trusted source (e.g., Microsoft). This ensures the security and reliability of the update process without needing to protect the confidentiality of the update contents.

Non Repudiation

The technique in Case 5 and 6 also supports non-repudiation: signing either the entire message or the message digest with one’s private key.

Non repudiation

Non-repudiation is a property of cryptographic systems that ensures that a party cannot deny the authenticity of a digital signature or the integrity of a message that they have signed. In other words, if a party signs a message or document using their private key, they cannot later claim that they did not sign it or that the message was altered after they signed it.

B can then prove to the court that A wrote the message and no one else did.

If A and B were to exchange messages using symmetric key cryptography only (assume that they have exchanged keys in person beforehand), will that support non repudiation?

Hash Function Requirements

The hash function used to produce message digest must fulfil a certain criteria:

- Deterministic: For a given input, the hash function always produces the same output. This property is crucial for ensuring consistency and predictability.

- Non-reversibility (very important!): Hash functions are designed to be one-way functions, meaning it should be computationally infeasible to reverse the process and obtain the original input from the hash value. This property is crucial for maintaining the integrity and confidentiality of hashed data. This encompasses two properties:

- Pre-image Resistance: Given a hash value, it should be computationally infeasible to determine the original input data. This property ensures that the hash function protects the confidentiality of the input data.

- Second Pre-image Resistance: Given an input and its corresponding hash value, it should be computationally infeasible to find another input that produces the same hash value. This property ensures that the hash function maintains the integrity of the input data.

-

Fixed Output Size: The hash function generates a fixed-size output regardless of the size of the input. This property makes it easier to work with in various applications.

- Fast Computation: Hash functions are designed to be computationally efficient, allowing them to process large amounts of data quickly. This efficiency is essential for real-time applications and systems with performance constraints.

-

Collision Resistance: It should be computationally infeasible to find two different inputs that produce the same hash value. This property ensures that the hash function can reliably distinguish between different inputs.

- Avalanche Effect: A small change in the input data should result in a significantly different hash value. This property ensures that even minor alterations to the input data produce vastly different hash values, enhancing the security of the hash function.

These characteristics collectively make cryptographic hash functions like SHA-256 essential building blocks in various security protocols and cryptographic applications.

Case 7: Secure Email

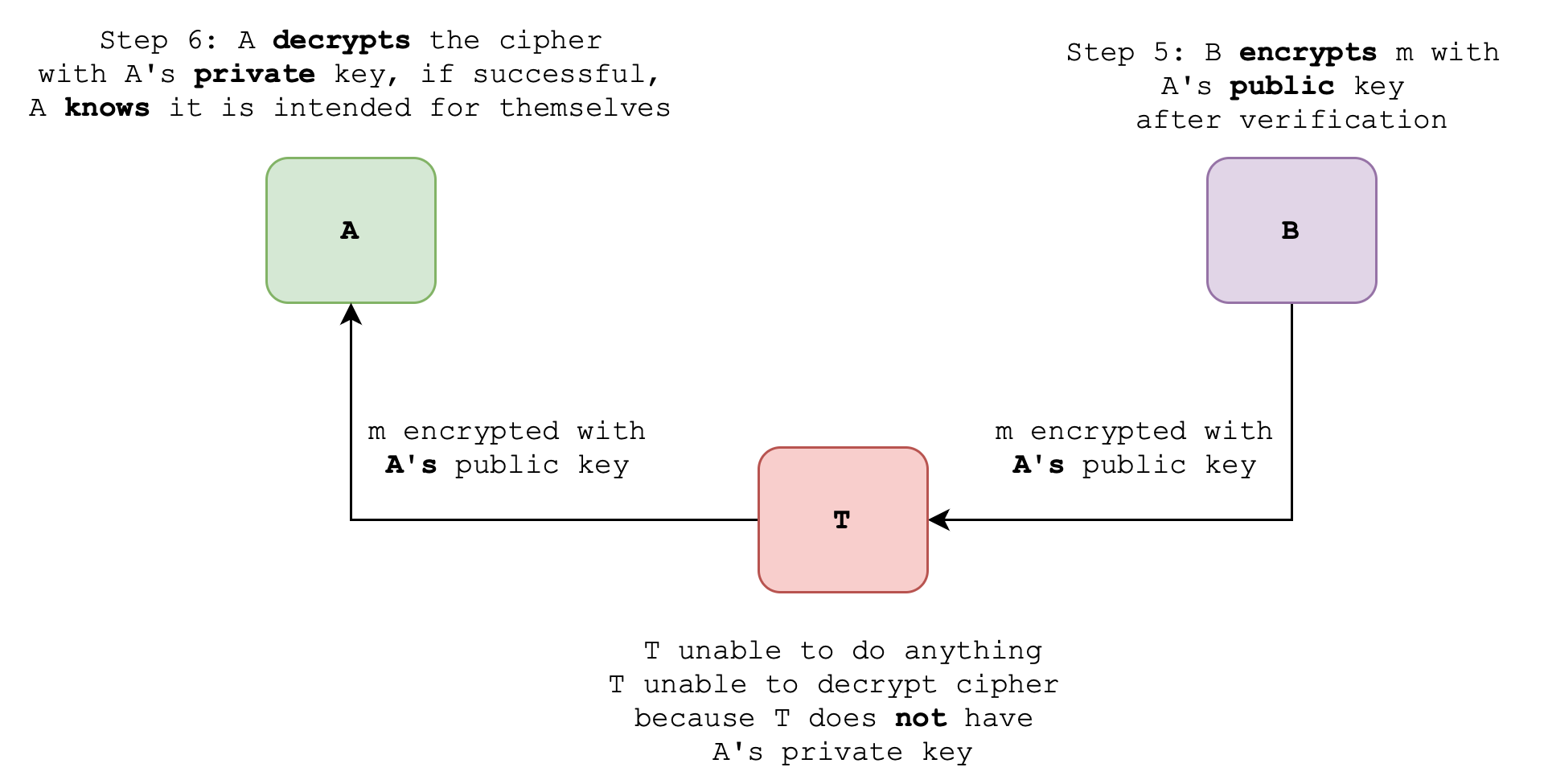

Both Case 5 and 6 ignores confidentiality as one of its security properties (simply not required). However, if communication between A and B must be secure, we need to find another way without fully utilising public key cryptography for the entire message exchanges. Recall that it is not realistic to encrypt lengthy messages using public-key cryptography. We can therefore use the public-key cryptography (+ digitally signed certificate by a trusted CA) to share a symmetric session key.

Session Key

Session Key

A session key is a temporary encryption key used for securing communication between two parties during a single communication session or transaction. It’s typically generated dynamically for each session and discarded after the session ends, reducing the risk associated with long-term key exposure. This session key is typically symmetric.

Any party can initiate to share the session key first, as long as the recipient you’re sending to has a public key (certified by CA). Here’s the general steps:

- B has to obtain A’s public key from its CA-issued certicicate

- B Generate a session key (e.g: using symmetric key cryptography)

- B encrypts the session key to be sent back to A

By encrypting the session key with A’s public key, B is certain that only A can decrypt the session key (since A’s private key is owned by only A). Then, subsequent messages are encrypted using the session key.

This technique therefore provides for the following security features. Assume that Nonce verification (to authenticate that B and A are both live) is already done prior to the session:

- Confidentiality: message is encrypted by shared session key, that is typically valid only for one session. No intruder can decrypt the messages in realistic time.

- Integrity: not exactly, depends on the type or format of data you’re sending, among other things. You might think that since the entire message is confidential (encrypted by session key), and can only be decrypted by the same session key, B or A should be certain that an intruder won’t be able to alter the message’s content on the fly. The hard part is knowing what’s the true content.

- Suppose B and A are just exchanging integers (bad protocol, yes but just using it as example), then if a malicious attacker randomly alters the bits, decryption by the symmetric key might result in an entirely new integer (not what the sender sent), and there’s no way for the receiver to know that that integer was sent by the sender.

- Hence extra care must be taken to ensure integrity, one way is to utilise Message Authentication Code or any protocol utilising one-way-functions.

- Authentication: A’s certificate is digitally signed by a trusted CA. This proves that A’s public key indeed belongs to A and therefore the session key shared by B can only be decrypted by A and no one else.

This technique alone does not support non repudiation: B cannot prove to the court that no one else but A wrote the message, because the symmetric key are owned by both A and B. It is possible that B wrote a message posing as A and later “claim” that this message is written by A.

Case 8: Secure email + non repudiation

If A needs to communicate securely with B and non-repudiation must be supported (e.g: prove that A’s messages are written by A), then A must provide a signed digest and encrypt both the message + encrypted hash together with the symmetric key:

Once B receives and decrypt the content: message + signed digest with the session key, B can:

- Hash the received message

- Decrypt the signed digest with CA-verified A’s public key

- Compare the two hashes to confirm message integrity, i.e: the message is sent and written by A

- If yes, this provides non-repudiation: the message is indeed sent by A (provable in court)

Three keys in total are utised to provide secure communication with non repudation: A’s public key, A’s private key, and Session Key.

Non-repudiation in asymmetric cryptography relies on the sender’s private key, which is kept secret and known only to the sender. This prevents the sender from denying their involvement in signing the message. If non-repudiation is needed for both A and B, then both A and B must have a set of CA-verified public-private key pair.

Summary

The essential security properties for secure network communication include confidentiality, integrity, authentication, and access/availability. Cryptography plays a pivotal role in fulfilling the first three properties, but ensuring access and availability requires additional measures like DNS caching to defend against DDoS attacks. Here, we detail practical applications that illustrate cryptographic mechanisms and their impact.

Plain Message Vulnerability In unencrypted communication, an attacker can easily impersonate a sender or modify messages, thereby breaching all three core security properties. Adding an IP header offers little protection, as attackers can still spoof the address to send deceptive messages.

Symmetric Encryption and Replay Attacks Introducing a shared secret password improves authentication and integrity, but without encryption, the secret can be exposed through eavesdropping. Even with symmetric encryption, attackers can replay messages, resulting in financial losses or fraudulent actions.

Nonce and Asymmetric Encryption Using asymmetric encryption with nonces ensures that each message is unique and fresh. By signing the nonce with a private key, the sender can authenticate themselves. However, without a trusted Certificate Authority (CA), there’s a risk of man-in-the-middle attacks that can compromise both authentication and integrity.

Role of Certificate Authorities CAs issue signed certificates, binding public keys to verified entities. When both parties rely on a trusted CA, they can securely verify each other’s identities and prevent MITM attacks. This approach is essential in digital communication for maintaining confidentiality and authenticity.

Message Digests and Non-Repudiation Cryptographic hash functions, such as SHA-256, generate fixed-length message digests to verify integrity efficiently. When paired with digital signatures, these digests ensure data hasn’t been altered and attribute the message to the original sender.

Session Keys for Efficient Secure Communication Using public-key cryptography to share symmetric session keys allows parties to encrypt subsequent messages efficiently. The session key ensures confidentiality during the exchange, though integrity verification requires careful implementation.

Secure Communication with Non-Repudiation Combining symmetric encryption with signed message digests provides non-repudiation. The recipient can verify the signature against the hash, confirming the message’s origin and integrity. However, both parties require a CA-verified key pair to provide mutual non-repudiation.

It is important that you take the time to appreciate the subtlety of each cases provided in this notes, e.g: how confidentiality, integrity, and authentication are or are not guaranteed. Do not rush into conclusions.

Appendix

Spoofing IP Address

To send a message with a spoofed IP address in Python, you can use the scapy library, which allows for crafting and sending packets at a low level. Here’s a simple example:

from scapy.all import *

# Craft an IP packet with a spoofed source IP

fake_ip = "192.168.1.100"

spoofed_packet = IP(src=fake_ip, dst="www.example.com") / ICMP()

# Send the packet

send(spoofed_packet)

In this example:

- We import the

scapylibrary, which provides functions for crafting and sending packets. - We craft an IP packet with a spoofed source IP address (

src="192.168.1.100") and a destination IP address (dst="www.example.com"). - We add an ICMP payload to the packet using

/ ICMP()to demonstrate a simple payload. - Finally, we use the

send()function to send the spoofed packet.

Eavesdropping

An eavesdrop attack, also known as passive eavesdropping or sniffing, involves intercepting and monitoring communications between two parties without their knowledge. Here’s how an eavesdrop attack is typically done:

-

Packet Sniffing: The attacker uses specialized software or hardware tools to capture network traffic passing through a network interface. This can be done by placing the sniffing device on a network segment or by compromising a network device.

-

Promiscuous Mode: The attacker configures the sniffing device to operate in promiscuous mode, allowing it to capture all network packets, including those not intended for the attacker’s device. In this mode, the network interface card (NIC) ignores the MAC address filtering and captures all packets on the network segment.

-

Packet Analysis: Once the attacker captures network packets, they analyze the captured data to extract sensitive information such as usernames, passwords, credit card numbers, or other confidential data transmitted in plaintext.

-

Decrypting Encrypted Traffic: If the intercepted communication is encrypted, the attacker may attempt to decrypt it using various cryptographic attacks, such as brute force attacks, dictionary attacks, or exploiting cryptographic vulnerabilities.

-

Passive Nature: One key characteristic of eavesdropping attacks is their passive nature. The attacker does not actively modify the intercepted data but merely listens in on the communication between the legitimate parties.

-

Stealthy Operation: Eavesdropping attacks are often difficult to detect since they do not disrupt the normal operation of the network. Unless proper security measures are in place, the attacker can silently intercept sensitive information without raising suspicion.

Overall, eavesdropping attacks pose a significant threat to the confidentiality of communication over a network, highlighting the importance of using encryption and other security measures to protect sensitive data from interception.

Tools for eavesdropping

Several applications and tools can be used for eavesdropping attacks, commonly known as packet sniffing or network sniffing tools. Here are some examples:

-

Wireshark: Wireshark is a widely-used network protocol analyzer that allows users to capture and interactively browse the traffic running on a computer network. It supports hundreds of protocols and can capture data from live networks or read data captured from a file.

-

tcpdump: tcpdump is a command-line packet analyzer available for Unix-like operating systems. It captures packets traversing a network interface and displays them in real-time or saves them to a file for later analysis.

-

Ettercap: Ettercap is a comprehensive suite for man-in-the-middle attacks on LAN. It features sniffing of live connections, content filtering on the fly, and many other interesting tricks. It supports active and passive dissection of many protocols and includes many features for network and host analysis.

-

Cain & Abel: Cain & Abel is a password recovery tool for Microsoft Windows. It allows easy recovery of various kinds of passwords by sniffing the network, cracking encrypted passwords using dictionary, brute-force, and cryptanalysis attacks, recording VoIP conversations, decoding scrambled passwords, and analyzing routing protocols.

-

dsniff: dsniff is a collection of tools for network auditing and penetration testing. It includes sniffing tools like dsniff, filesnarf, mailsnarf, msgsnarf, URLsnarf, and others that can be used for eavesdropping on different types of network traffic.

-

WinPcap: WinPcap is a library for Windows operating systems that provides low-level network access. It is used by many packet sniffing applications on Windows, including Wireshark and tcpdump for Windows.

These tools are often used by network administrators, security professionals, and attackers alike to analyze network traffic, troubleshoot network problems, or exploit security vulnerabilities. However, it’s important to note that using these tools for unauthorized access to network traffic or without proper authorization can be illegal and unethical. Always use these tools responsibly and with the appropriate permissions.

Certificate

A certificate contains several pieces of information, including:

-

Public Key: The public key of the entity (e.g., a website) that the certificate is issued to. This key is used for encryption and verifying digital signatures.

-

Identity Information: Information about the entity the certificate is issued to, such as its domain name, organization name, and location.

-

Issuer Information: Information about the Certificate Authority (CA) that issued the certificate, including its name and digital signature.

-

Validity Period: The period during which the certificate is considered valid, including its start and expiry dates.

-

Certificate Serial Number: A unique identifier assigned to the certificate by the issuing CA.

-

Key Usage: Specifies the cryptographic operations (e.g., encryption, digital signature) that the public key in the certificate can be used for.

-

Signature Algorithm: The algorithm used by the CA to sign the certificate.

-

Digital Signature: A digital signature generated by the CA using its private key to bind the certificate’s contents to the CA’s identity, ensuring the certificate’s authenticity.

-

Extensions: Additional information or attributes associated with the certificate, such as subject alternative names (SANs) for SSL/TLS certificates.

-

Certificate Chain: For SSL/TLS certificates, the certificate may also include the intermediate certificates that link the entity’s certificate to the root certificate of the CA.

Overall, a certificate serves as a digital identity card, providing information about the entity it represents and enabling secure communication through cryptographic mechanisms.

Chosen Hash Function

When you send a signed message digest, typically as part of a digital signature, the other side needs to know which hash function you used in order to compute the hash value of the original message and verify the signature. There are a few common methods for communicating the hash function used:

-

Protocol Specification: In many cases, the protocol or standard you’re following will specify which hash function to use. For example, if you’re using a protocol like TLS (Transport Layer Security) or a digital signature standard like PKCS#1 (Public Key Cryptography Standard #1), it will specify the hash function to use (e.g., SHA-256).

-

Metadata: You can include metadata along with the signed message digest that explicitly states which hash function was used. This metadata can be part of the message format or included in a separate header.

-

Default or Negotiated Algorithm: In some cases, there may be default hash functions agreed upon by both parties. If not explicitly specified, the receiver might assume a default hash function agreed upon beforehand or negotiate the hash function to use during the communication.

-

Out-of-Band Communication: Before exchanging signed messages, the parties involved can communicate out-of-band (e.g., through a separate channel like email or a conversation) to agree on the hash function to be used.

-

Digital Certificates Specification: CA-issued certificates can include information about the hash function used for generating digital signatures. In the context of digital certificates, this information is typically found within the certificate’s metadata, specifically within the signature algorithm field.

When a digital certificate is issued, it is signed by a certificate authority (CA) using a specific signature algorithm, which includes a hash function. The signature algorithm field in the certificate indicates both the cryptographic algorithm used for the signature and the hash function used as part of that algorithm.

For example, in an X.509 certificate, which is the standard format for public key certificates, the signature algorithm field might specify something like “SHA256withRSA” or “SHA384withECDSA.” This indicates that the SHA-256 or SHA-384 hash function was used along with the RSA or ECDSA algorithm, respectively, for generating the digital signature on the certificate.

By examining the signature algorithm field in the digital certificate, the recipient can determine which hash function was used for signing the certificate and, by extension, for any signed data associated with that certificate. This information is crucial for verifying the integrity and authenticity of digital signatures.

Regardless of the method used, it’s essential for both parties involved in the communication to agree on the hash function to ensure that the signature verification process is successful.

50.005 CSE

50.005 CSE