50.005 Computer System Engineering

Information Systems Technology and Design

Singapore University of Technology and Design

Natalie Agus (Summer 2025)

Domain Name System

Detailed Learning Objectives

- Explain Basics of DNS

- Explain how internet naming and addressing works.

- Explain the difference between mnemonic names and IP addresses

- Explain what DNS is and its role in the internet.

- Appreciate the hierarchical and decentralized nature of DNS.

- Describe how DNS translates human-friendly domain names into IP addresses.

- Identify Basic DNS Operations

- Explain the process of accessing a website using DNS.

- Explain the role of local DNS servers and authoritative DNS servers.

- Describe the steps involved in a DNS lookup, from entering a domain name to accessing the website.

- Identify the Structure and Components of DNS

- Explain the hierarchical structure of DNS, including root servers, top-level domain (TLD) servers, and authoritative name servers.

- Describe design principles of the DNS infrastructure and query

- Describe the purpose and function of each type of DNS server.

- Assess the importance of local domain name servers and their role in DNS resolution.

- Analyze DNS Query Types

- Differentiate between iterative and recursive DNS queries.

- Explain the resolution order for both iterative and recursive queries.

- Explain how DNS queries are processed and the load distribution between clients and servers.

- Explain DNS Services and Features

- Identify additional services provided by DNS, such as host aliasing, mail server aliasing, and load distribution.

- Explain the general concept of DNS caching

- Relate to the significance of DNS in maintaining strong modularity, fault isolation, and scalability.

These learning objectives aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the Domain Name System (DNS), including its operations, structure, query types, services, and security aspects.

Domain Name System

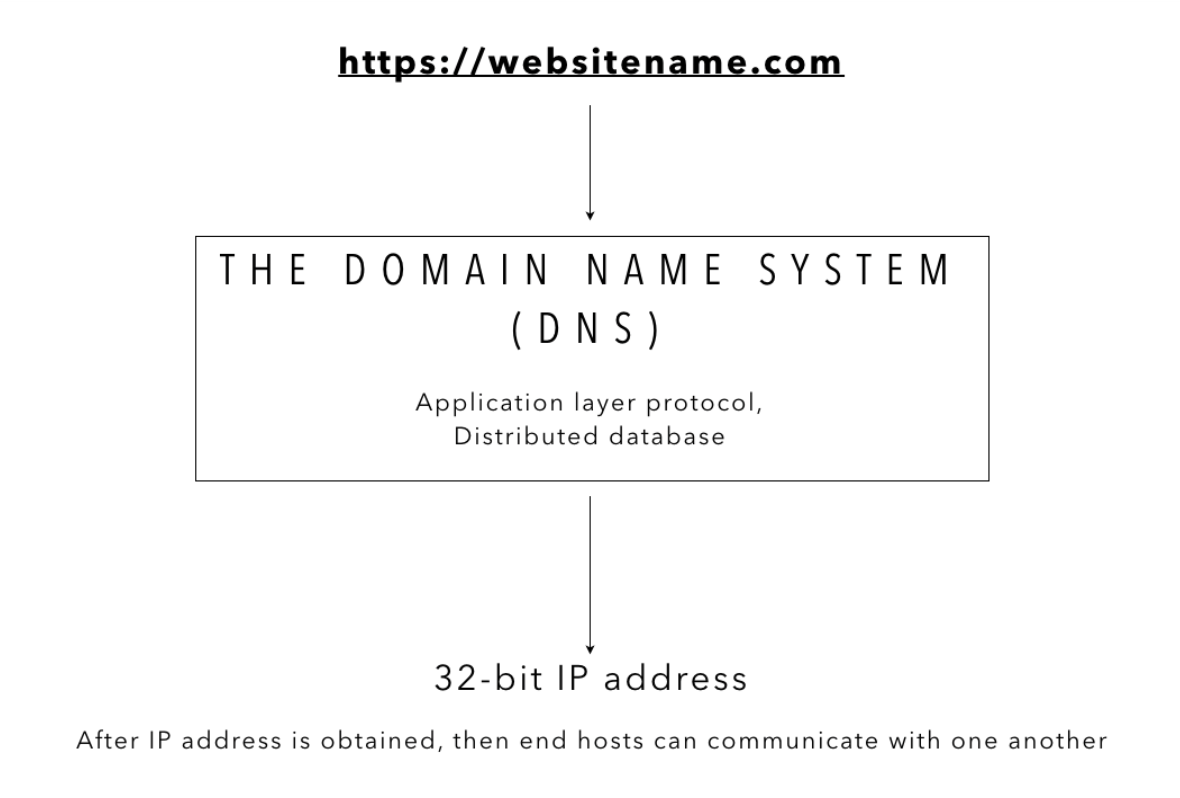

The Domain Name System (DNS) is a naming system for computers, services, or other resources connected to the Internet or a network of computers.

It is a hierarchical and decentralized naming system that allows computers, services, or resources connected to the Internet or a private network to be identified and accessed. It translates human-friendly domain names, like example.com, into the numerical IP addresses needed by computers to communicate with each other. This system makes browsing the internet and accessing network resources easier for users while handling the technical mapping in the background.

DNS is both a naming system and a protocol, read along to find out more.

Motivation

Imagine you’re in your university library, working on a research project, and you type in a website like example.com into your browser. The site loads almost instantly. This quick response is thanks to the Domain Name System (DNS), which works like the internet’s phone book, converting user-friendly names to the numerical IP addresses computers use to communicate.

Here’s what happens when you access a website through the campus network:

-

Enter a Domain Name: You type

example.cominto your browser. -

University DNS Server: Your computer queries the local DNS server maintained by the university, which could be located in a data center on campus and maintained by the school’s IT team. If the server has recently looked up

example.com, it knows the IP address and sends it back to your computer. - Further Lookups: If the university server doesn’t know the IP address, it starts asking other DNS servers on the internet:

- It first contacts a global root server that directs it to the top-level domain (TLD) servers for

.com. - The TLD servers then point to authoritative servers responsible for

example.com.

- It first contacts a global root server that directs it to the top-level domain (TLD) servers for

-

Authoritative DNS Server: The authoritative DNS server provides the final answer with the correct IP address for

example.com. - Access the Website: With the IP address provided, your computer can now connect directly to

example.com.

In summary, the university’s DNS server in the data center acts as an intermediary to quickly find the correct IP address for any website you access, enabling seamless browsing on campus.

IP Addresses

IP addresses (32 bits or 64 bits) are used to address datagram by routers:

- For instance, IPv4 (32 bits)

172.217.194.99(dotted notation a.b.c.d in groups of unsigned bytes – octet)- This is convenient for hierarchical routing: facilitates routing (remote router uses short prefix of destination IP address only to decide next hop – much smaller routing table)

DNS is a system that acts as a phonebook. We will remember our friends by their names, and not their contact number. When we want to actually contact them, we need to translate their names into their contact numbers using our phonebook. The DNS is much like our phonebook, where it translates between domain name and IP addresses.

Head to this appendix section if you’d like to find the IP address of the DNS server your smart devices is currently using.

Characteristics

Distributed Database

The DNS is implemented in hierarchy of name servers. We do not centralise DNS because:

- Need to avoid single point of failure,

- Avoid creating a bottleneck traffic volume

- Avoid distant centralized databases, causing long delays for lookups (remember DNS lookup is only name-IP translation! We haven’t even looked up the website yet)

- Need to support ease of maintenance (add/delete/change translation). We do not want to keep going to one place to do this.

Furthermore, a centralised DNS does not scale.

Application Layer Protocol

The Domain Name System (DNS) is vital as one of the core functions of the internet. It enables hosts and name servers to communicate, resolving user-friendly names into numerical IP addresses so computers can locate each other and exchange data. As an application-layer protocol, DNS operates at the top of the Internet Protocol Suite, handling requests from other applications and services to ensure seamless access to network resources.

DNS is implemented at the network’s edge, managing complexity through a hierarchical and decentralized system. Key features of this structure include:

- Hierarchical Organization: The hierarchical arrangement of root servers, top-level domains, and authoritative name servers ensures efficient and organized domain name resolution.

- Edge Complexity: By placing complexity at the network’s edge, DNS remains scalable and effective in handling the growing demands of the internet.

DNS Services

Apart from providing hostname to IP address translation, DNS also provides the following services:

- Host aliasing: map alias names to canonical name

- Mail server aliasing

- Load distribution: replicated web servers such that many IP addresses correspond to one name

DNS Structure

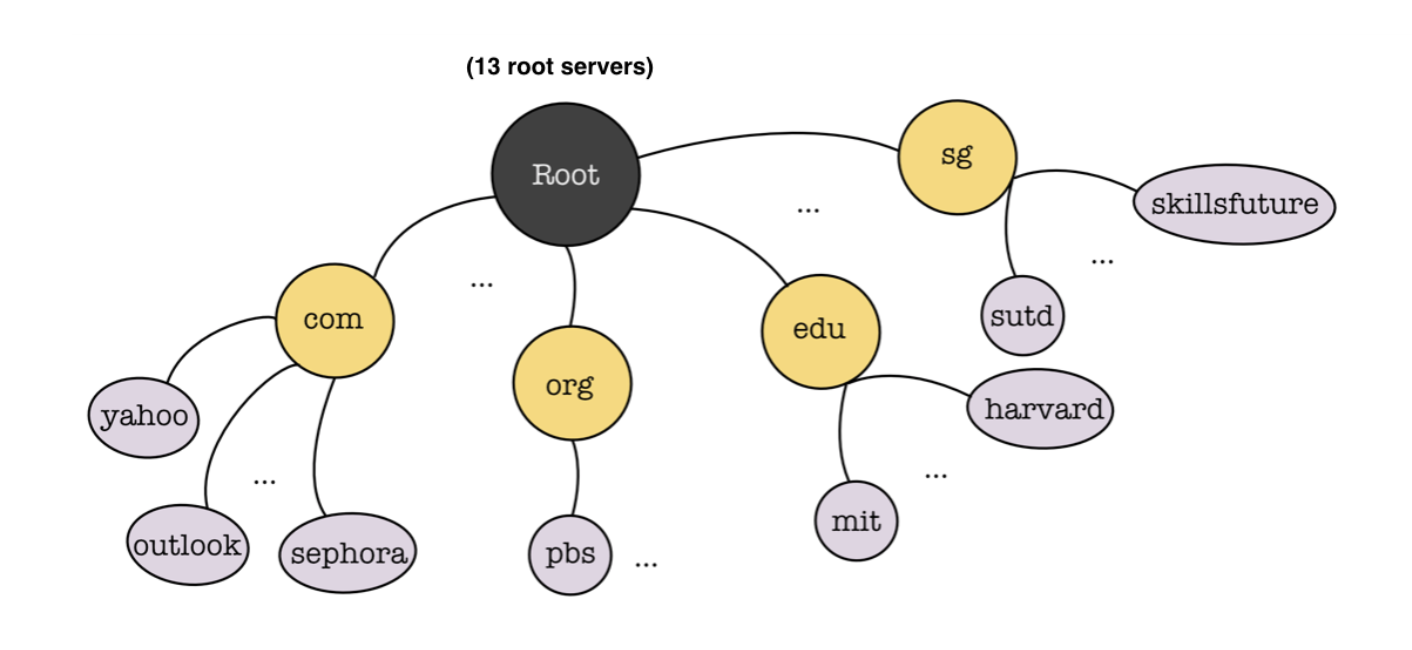

DNS is a distributed and hierarchical database.

Root Server

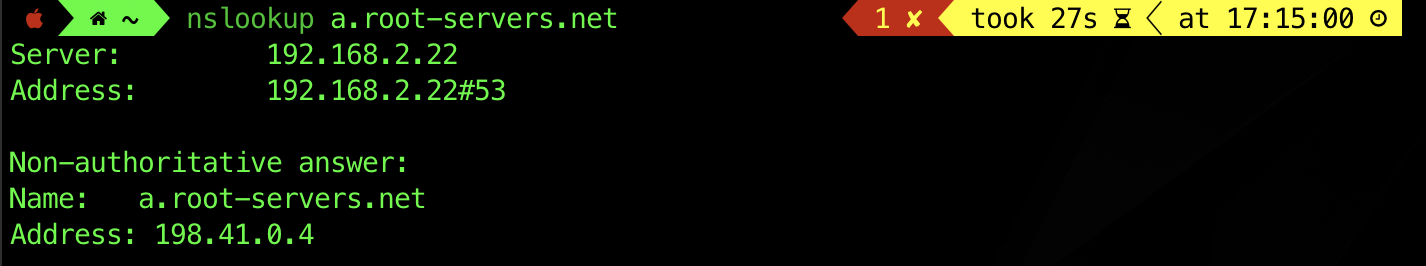

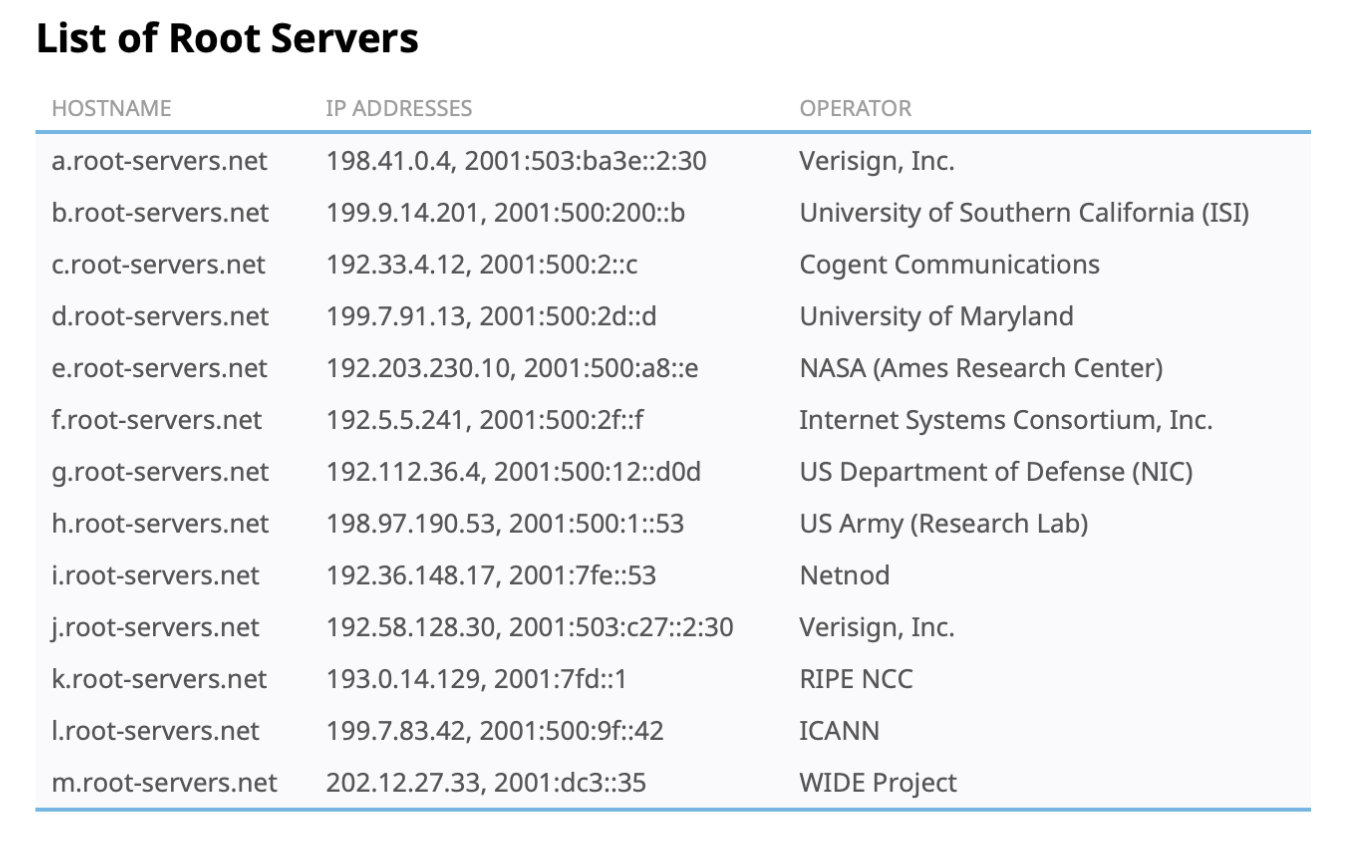

Root Server (highest in the hierarchy): contacted by local name servers (or end hosts explicitly configured for it) that cannot resolve names. The Root Server does not provide the final answer to the query (i.e., it doesn’t resolve the domain name directly); instead, it directs the query to the appropriate Top-Level Domain (TLD) server (like .com, .org, etc.). There are 13 root servers in the world. Find the list at http://root-servers.org/.

You can look for its individual IP, e.g: a.root-servers.net IP:

The root servers are basically a fixed set of name servers that maintain a list of the authoritative (master/slave) name servers for every registered top level domain (e.g: edu., gov., com., etc). They may be located at:

- Companies contracted to provide the service by ICANN (The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) or

- Government institutions.

Top Level Domain (TLD)

TLD Server: responsible for anything after the last dot, such as .com, .edu, .sg etc. They are maintained by large organizations or countries. For example, Verisign global registry services is responsible for .com domain.

Authoritative Name Servers

Authoritative Name Servers: organization’s own DNS server, providing authoritative (final, no need further query) hostname to IP mappings for organization’s named hosts. They’re maintained by the organization itself or by internet provider / cloud service management system like AWS.

Local Domain Name Servers

Local DNS: also called DNS resolvers are used by DNS clients (our computers or smart devices) to resolve domain names to IP addresses. They serve as proxy for hosts to make DNS queries, and forward queries to the hierarchy:

- Local DNS Name Servers have local cache of recent name-to-address translation pairs

- Need to maintain and update these caches from time to time

Common DNS resolvers include

- ISP-given DNS resolver

- Google DNS resolver: 8.8.8.8

- Cloudflare DNS resolver: 1.1.1.1

DNS Name Resolution

There are two ways to resolve the hostname-IP translation: iterative and recursive.

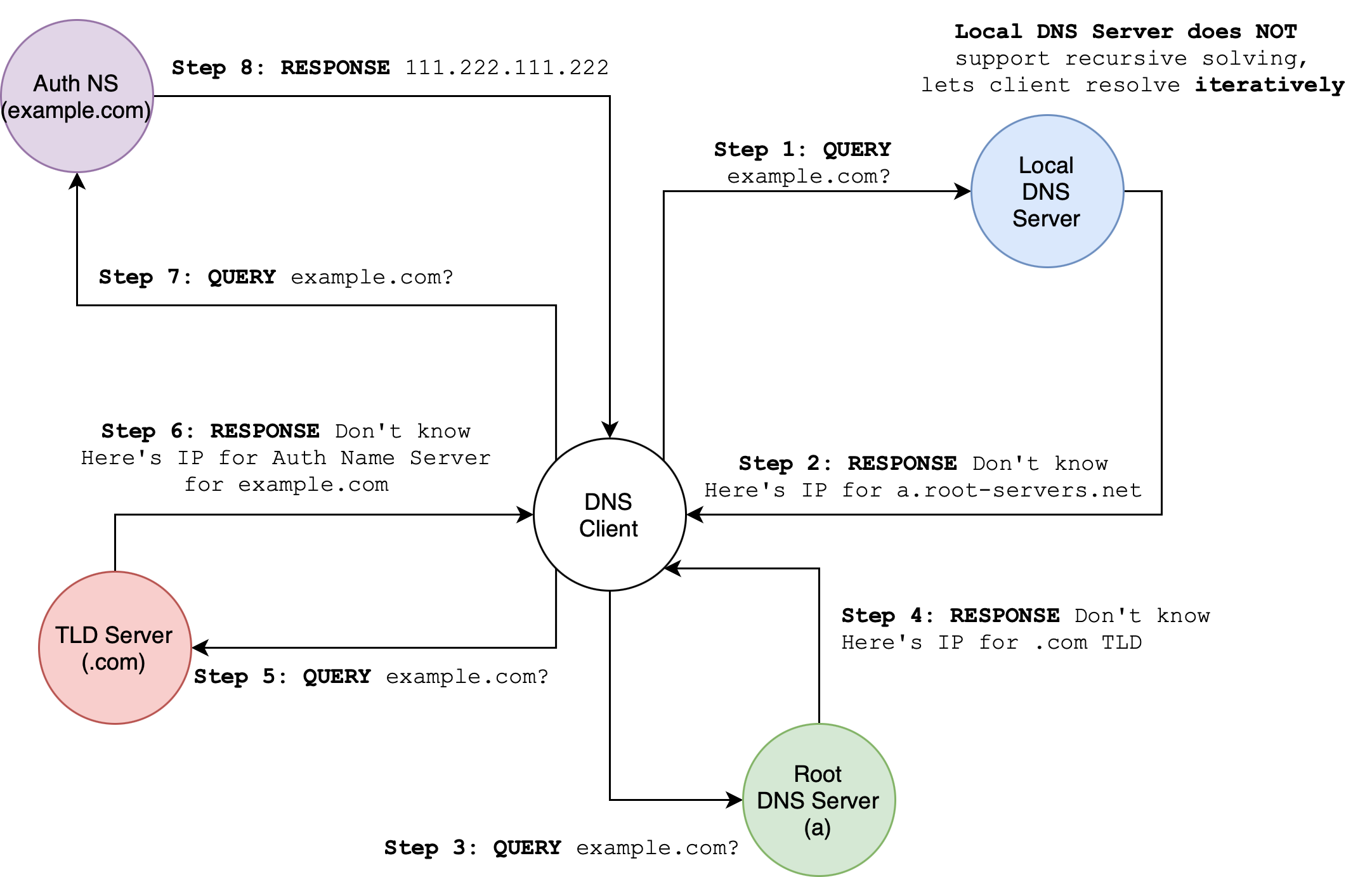

Iterative Query

In an iterative DNS query, the DNS client allows the DNS server to return the best answer it can. If the queried server does not have the answer, instead of asking other servers itself, it returns a referral to other more authoritative DNS servers.

The resolution order is as drawn:

DNS Client

Majority of the “work” (resolution) is done by the DNS client. A DNS client can be any application or tool that initiates DNS queries, such as CLI tools like

dig, web browsers, OS DNS Resolver, email clients, etc.

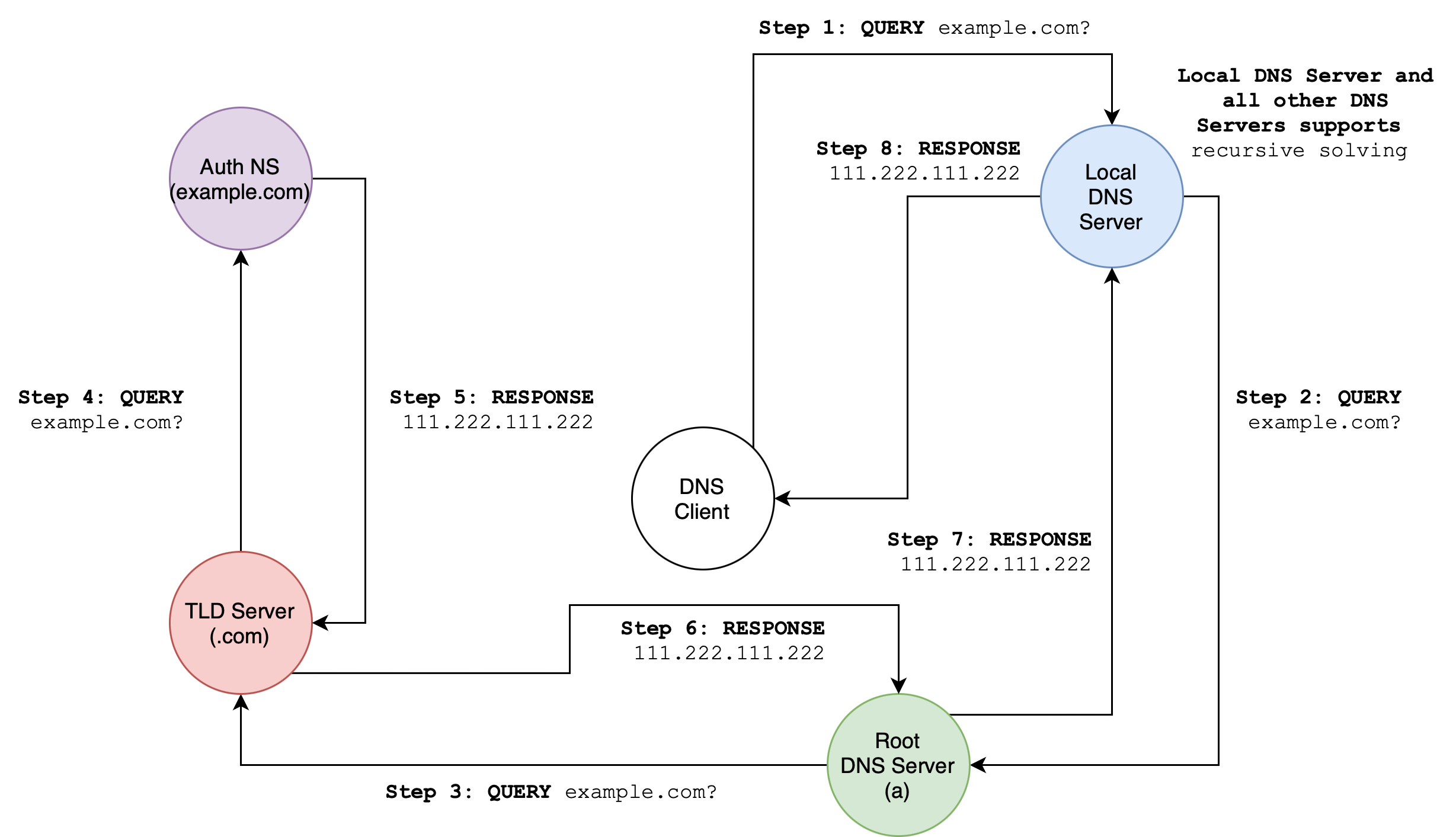

Recursive Query

A recursive DNS lookup is where one DNS server communicates with several other DNS servers to hunt down an IP address and return it to the client. The DNS server does all the work of fetching the requested information. This is in contrast to an iterative DNS query, where the client communicates directly with each DNS server involved in the lookup.

We put the burden of name resolution on the contacted name server. This puts a heavy load at the upper hierarchy.

The resolution order is as drawn:

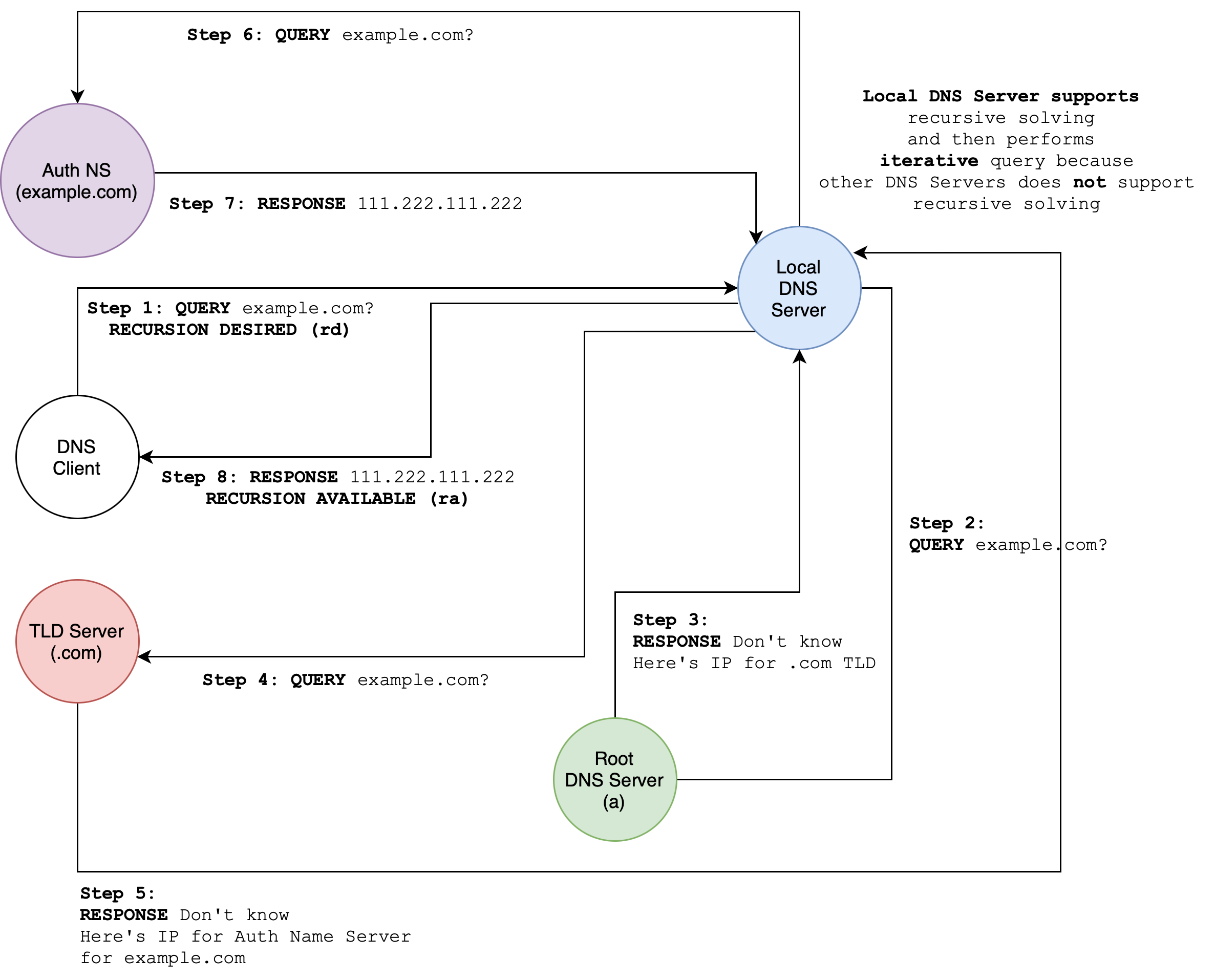

Potentially Misleading Information

Note that the diagram above can be slightly misleading (although this is the exact illustration taken from the KR book). It seems to point out that all other DNS servers in the path is doing the work and then answer is propagated back. This might be done for educational purposes. In practice, the root servers and TLD servers do not do the work for us. When a recursive query is made by the DNS client / user, the local DNS server (if it supports recursive query) will perform iterative querying to resolve the answer for the user. In the eyes of the user, the Local DNS server that supports recursive query does all the work, and hence we regard it as recursion available.

The next section explains it more.

Possible Source of Confusion

In some books, it is said that recursive query means the local DNS server takes responsibility for resolving the domain name on behalf of the client.

This means that if the query is not cached, the local DNS server will then perform iterative query on behalf of the client upon receiving a DNS query with an rd flag (instead of propagating recursive queries as shown in the our course book, requiring all DNS servers in the path to “do the work”). In other words, DNS servers that supports recursive query typically perform iterative queries when resolving domain names.

Finally, the local DNS server then caches the result to optimize future queries. Here’s a diagram to visualize this process:

Do not fret too much about these details. These protocols change over time. What’s important is that you realise these differences:

- Recursive Query:

- In a recursive query, the DNS server does all the work of fetching the requested information. The client (such as your computer or device) sends a query to the DNS server, and the server then queries other DNS servers on behalf of the client until it gets the final answer. The client receives a single response with the requested information.

- It does not matter how exactly the Local DNS Server resolves your query behind the scene: be it iteratively or that all other DNS servers in the path recursively solve the query for you.

- Iterative Query:

- In an iterative query, the DNS server does not fetch the complete answer for the client. Instead, it responds with a referral to another DNS server that may have the answer. The client then has to query the referred DNS server, and this process continues iteratively until the client gets the final answer.

A local DNS server provided by an ISP typically supports recursive queries rather than iterative queries, while Root and TLD servers only support iterative queries. ISPs typically configure their DNS servers to operate in a recursive mode to simplify the process for end users, providing a straightforward and efficient resolution process. This means that when you use your ISP’s DNS server, it will handle the entire process of querying other DNS servers as needed to resolve your request, rather than requiring your device to make multiple iterative queries.

Who decides whether a query should be iterative or recursive?

The type of DNS query (whether iterative or recursive) is determined by the client making the query and the configuration of the DNS server receiving the query.

DNS Client need to specify whether the query is iterative or recursive. DNS server will then respond depending on its configuration. Hence DNS resolution behavior depends on both the configuration of the DNS server and the type of query received from the client.

Let’s look at a simple example on how web browsers (DNS client) handles DNS queries.

How Web Browsers Handle DNS Queries

- Browser Initiates a DNS Query:

- When you enter a URL in the browser’s address bar (e.g.,

http://example.com), the browser needs to resolve the domain name to an IP address.

- When you enter a URL in the browser’s address bar (e.g.,

- Browser Requests DNS Resolution from the OS DNS Resolver:

- The browser sends a DNS query to the operating system’s DNS resolver. The browser itself does not directly perform recursive or iterative queries; it relies on the OS resolver to handle this.

- Read this appendix section to know more about OS DNS Resolver if you wish (out of syllabus). For now, to make things simple we treat Browser + OS DNS Resolver as a single “DNS Client” entity.

- OS Resolver Checks Cache:

- The OS resolver first checks its local cache to see if it has a recent answer for the queried domain name. If it has the answer cached, it returns it to the browser immediately.

- OS Resolver Sends a Recursive Query to the Local DNS Server:

- If the OS resolver does not have the answer cached, it sends a recursive query to the local DNS server (often provided by your ISP or set up in your network configuration).

- A recursive query means the OS resolver is asking the local DNS server to handle the entire resolution process and return the final answer.

- Local DNS Server Checks Cache:

- The local DNS server receives the recursive query and then checks its cache. It will return the queried IP if available in its cache.

- If the IP is not cached, it then performs the necessary iterative queries to resolve the domain name (if supported).

- This involves querying the root DNS servers, TLD DNS servers, and authoritative DNS servers as needed.

- The local DNS server follows the DNS hierarchy step-by-step to find the authoritative server for the domain and obtain the IP address.

- If the local DNS server does not support recursive query, it will return a best answer, e.g: IP of root DNS servers.

- Response Returned to the OS Resolver:

- If OS Resolver receives the actual IP address (recursion is available or cached in the local DNS server), then it will return the IP address immediately to the Browser.

- Else, this means that recursion is not available, and the OS Resolver will perform iterative query (querying the root DNS servers, TLD DNS servers, and authoritative DNS servers as needed) until an IP address is obtained (if any).

- Response Returned to the Browser:

- The browser uses the resolved IP address (if any) to establish a connection to the web server and load the webpage.

- It is entirely possible that the queried domain name does not return in any IP addresses. The web browser will display some kind of

SERVER NOT FOUNDerror message to indicate the status to the user.

In essence, while the browser itself initiates the DNS resolution process, the heavy lifting of recursion and iteration is managed by the OS resolver and local DNS servers. This multi-layered approach optimizes performance and ensures efficient DNS resolution.

Summary

DNS is a distributed database that provides name-IP translation. Distributed system of servers provide scalability.

The presence of DNS protects domains. The same name can point to a different physical machines hence allows for:

- Strong modularity,

- Strong fault isolation

We can also conclude that DNS provides indirection (name to IP address) as its core design principle. This has many virtues:

- Late binding at runtime, e.g: physical server can move around with different IP and keeping the same name

- Many-to-one mapping: aliasing. Some people use multiple domains aliased to a single site as part of their search engine strategy.

- One-to-many mapping: the same domain name can have many IP addresses. This is useful for load balancing.

Late Binding

Late binding in DNS refers to delaying the resolution of a domain name to an IP address until the last possible moment to optimize routing based on current network conditions, server load, and user location. This approach enhances performance, load balancing, and resource utilization.

For example: When a user types

google.cominto their browser, a DNS request is sent to resolve google.com to an IP address. At this stage, Google’s authoritative DNS server responds with an IP address. This IP address usually points to a Google load balancer or a CDN node, not directly to the final server.This node has the most current information about Google’s global network, including server loads, user locations, and network conditions. The user’s browser then sends an

HTTP/srequest to the IP address provided (the load balancer or CDN node).Internal Routing and Final Binding: The load balancer/CDN node then resolves this HTTP/s request to the optimal Google server’s IP address, which is currently the best choice based on the latest data. This server could be geographically closer to the user or less loaded.

Note that the load balancer or CDN node is not a DNS server, it just helps to route HTTP/s requests to the most optimum Google webserver.

Appendix

Finding DNS Server

Finding the DNS server your computer is using can be helpful for troubleshooting network issues or simply for informational purposes. Here’s how to do it on different operating systems:

Windows

- Open Command Prompt: Press

Win + R, typecmd, and hitEnter. - Run the

ipconfig /allCommand: Typeipconfig /allin the Command Prompt and pressEnter. Scroll through the information until you find the “DNS Servers” entry. The IP addresses listed are your DNS servers.

macOS

- Open Terminal: You can find Terminal in Applications under Utilities, or you can search for it using Spotlight.

- Run the

scutil --dnsCommand: Typescutil --dnsin the Terminal and pressEnter. Look for “nameserver” entries under the DNS configuration section. These are your DNS servers.

Linux

- Open a Terminal: Use a shortcut or find it in your applications menu.

- Check the resolv.conf File: Type

cat /etc/resolv.confin the Terminal and pressEnter. This file contains a list of DNS servers; look for lines starting withnameserver. The IP addresses followingnameserverare your DNS servers.

On a Smartphone

- Android:

- Go to

Settings>Network & Internet>Wi-Fi. - Tap on the Wi-Fi network you are connected to.

- Look for DNS settings, which might be under

Advanced options.

- Go to

- iOS:

- Go to

Settings>Wi-Fi. - Tap the information (

i) icon next to the network you are connected to. - Scroll to the DNS section to see the DNS servers.

- Go to

These steps will help you identify the DNS server addresses your device is currently using.

Common Terminologies

Below are some terminologies that are related to the topic and might be useful to fully appreciate the chapter: DNS Namespace: represent the entire DNS structure tree (all nodes)

Domain:

- Logical division of DNS namespace

- Represents a the entire set of names / machines that are contained under an organizational domain name (subtree), eg:

- “.com” websites are part of the “com” domain,

- en.wikipedia.com and id.wikipedia.com websites are part of the “wikipedia.com” domain.

Zone: physical division of DNS namespace

- DNS namespace can be broken into zones for which individual DNS servers are responsible. Each zone has its own zone file.

A zone file is a plain text file stored in a DNS server that contains an actual representation of the zone and contains all the records for every domain within the zone. Zone files must always start with a Start of Authority (SOA) record, which contains important information including contact information for the zone administrator.

- Unlike “domain” that’s a subtree, a zone can just be a bunch of sibling nodes.

- A DNS zone is not necessarily associated with one server, so two servers or more can store the same copy of the zone.

- A DNS server can also contain multiple zones.

- If a domain is not subdivided to subdomains, then domain is equivalent to the zone

Example about DNS Zone

Imagine you own a domain example.com. This domain can have various subdomains, such as www.example.com, mail.example.com, or shop.example.com. Each of these can technically be part of a different DNS zone, but they might also all be in one zone, depending on how you choose to organize your DNS records.

Example 1: Single DNS Zone for All Records

- Domain:

example.com - DNS Zone: In this scenario, you might have a single DNS zone for

example.comthat includes all the DNS records for the domain and its subdomains. The zone file could include:Arecord forexample.compointing to192.168.1.1CNAMErecord forwww.example.compointing toexample.comMXrecord forexample.comto manage email servicesArecord forshop.example.compointing to192.168.1.2

Example 2: Multiple DNS Zones for Different Purposes

- Domain:

example.com - DNS Zone 1: Main zone for

example.comArecord forexample.compointing to192.168.1.1MXrecord forexample.com

- DNS Zone 2: Separate zone for the subdomain

shop.example.comArecord forshop.example.compointing to192.168.1.2- Separate administrative settings specific to the e-commerce platform

How DNS Zones Work

The key point about DNS zones is that they are administrative blocks that allow you to manage how different parts of your domain’s namespace are handled. Each zone can be hosted on the same or different DNS servers. If you delegate a subdomain like shop.example.com to a different DNS zone, you can specify different DNS servers for it, which might be managed by a different team or a third-party service, helping distribute the load and administrative responsibilities.

Practical Application

In practice, if you manage a large organization, you might want DNS zones for different departments or functions to separate administrative control or enhance security. For example, IT might manage the main domain’s DNS records, while marketing manages a subdomain for promotional sites in a different DNS zone.

Understanding DNS zones as these distinct entities that contain DNS records for specific namespaces under your domain can help you manage and delegate DNS more effectively.

OS DNS Resolver

The OS DNS resolver is a crucial component of the operating system, responsible for handling DNS queries from applications, caching results, and communicating with external DNS servers. It provides a centralized, efficient, and secure way to manage DNS resolution for all applications running on the system.

The OS DNS resolver functions as a system service or library within the operating system. It runs in user mode and need to make system calls when necessary like any other system programs.

The browser does not send DNS queries directly to the local DNS server for several reasons, primarily revolving around system design, efficiency, and security.

- System Design and Abstraction

- Separation of Concerns:

- The operating system (OS) is designed to handle network-related tasks, including DNS resolution, to provide a consistent and centralized way of managing network configurations and queries. This separation of concerns allows applications like web browsers to remain simpler and more focused on their primary tasks.

- Separation of Concerns:

- Efficiency and Caching:

- Centralized Caching:

- The OS resolver maintains a cache of DNS responses. This centralized cache ensures that if multiple applications request the same domain, the query is resolved once, and cached responses are reused, improving efficiency and reducing redundant network traffic.

- System-wide Configuration:

- DNS settings, such as the addresses of local DNS servers, are typically configured at the OS level. By querying the OS resolver, applications automatically use the system-wide DNS settings without needing to manage these configurations individually.

- Centralized Caching:

- Security:

- Unified Security Policies:

- Handling DNS queries at the OS level allows for the application of system-wide security policies and mechanisms, such as DNSSEC validation, firewall rules, and other network security measures.

- Reduced Attack Surface:

- By not allowing each application to directly interact with external DNS servers, the system reduces the potential attack surface. Centralized DNS resolution via the OS resolver can help mitigate certain types of DNS-related attacks.

- Unified Security Policies:

- Portability and Compatibility:

- Abstracting Network Configuration:

- Applications like web browsers are designed to be portable across different operating systems and environments. By relying on the OS resolver, they avoid dealing with the complexities and variations of network configurations on different platforms.

- Consistent Behavior: - Relying on the OS resolver ensures consistent DNS resolution behavior across different applications and system updates, providing a more predictable and stable environment.

- Abstracting Network Configuration:

- Performance Optimization:

- Efficient Resource Use:

- The OS resolver can optimize DNS resolution for all applications on the system, avoiding redundant queries and managing network resources more effectively.

- Efficient Resource Use:

How it Works in Practice

- Browser Request:

- The browser sends a DNS resolution request to the OS resolver using standard APIs provided by the operating system.

- OS Resolver Action:

- The OS resolver checks its cache. If the requested domain is cached, it returns the IP address to the browser.

- If not cached, the OS resolver sends a recursive query to the configured local DNS server.

- Local DNS Server:

- The local DNS server performs the necessary iterative queries to resolve the domain name and returns the result to the OS resolver.

- Response to Browser:

- The OS resolver caches the response and provides the resolved IP address to the browser.

Summary:

- Abstraction and Simplification: Delegating DNS queries to the OS resolver simplifies application development and ensures that network configurations are consistently applied.

- Efficiency and Caching: Centralized DNS caching at the OS level improves performance and reduces redundant queries.

- Security: Centralized handling of DNS queries enhances security by applying unified policies and reducing the attack surface.

- Portability and Compatibility: Relying on the OS resolver ensures that applications remain portable and compatible across different environments.

By following this approach, the overall system is more efficient, secure, and easier to manage.

50.005 CSE

50.005 CSE