- Possible Security Attacks

- Cryptography

- Summary

- Appendix

50.005 Computer System Engineering

Information Systems Technology and Design

Singapore University of Technology and Design

Natalie Agus (Summer 2025)

Network Security and Cryptography

Detailed Learning Objectives

- Identify Important Security Properties (CAP)

- Describe the concepts of confidentiality, integrity, authentication, and access/availability in network security.

- Explain the purpose and scope of cryptography in ensuring secure communication over the internet.

- Explain Symmetric Key Cryptography

- Describe the principles of symmetric key cryptography.

- Compare and contrast DES and AES algorithms.

- Evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of symmetric key encryption.

- Explain Asymmetric Key Cryptography

- Define asymmetric key cryptography and its role in secure communication.

- Analyze the RSA algorithm and its components.

- Explain the key generation process in RSA.

- Demonstrate encryption and decryption using RSA.

- Illustrate the process of digital signing and verification with RSA.

- Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of RSA in different contexts.

- Discuss Practical Considerations

- Evaluate the computational efficiency of RSA compared to symmetric key algorithms.

- Apply the concept of session keys in improving efficiency in message exchanges.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of cryptographic solutions in mitigating specific security threats.

The learning objectives encompass understanding security properties, identifying various security attacks, comprehending cryptography fundamentals including symmetric and asymmetric key cryptography, exploring the RSA algorithm, discussing practical considerations such as computational efficiency and session keys, synthesizing security measures, and analyzing current and future challenges in network security.

Throughout this chapter, we are going to focus on these four security properties pertaining to exchanging messages through the internet that we care about:

- Confidentiality: only sender and receiver should understand the message contents

- Integrity: sender, and receiver want to confirm that the message is not altered without detection during transit

- Authentication: sender, and receiver both can confirm the identity of one another

- Access and Availability: internet services must be accessible and available to users

Note that not all scenarios require all four of these properties to hold. It depends on a case-by-case basis, for instance: there exist scenarios whereby confidentiality is not important (not a requirement), but the other 3 are. For example: broadcasting of emergency alerts.

We will discuss how these properties are threatened, and ways to ensure that these properties hold. In real life, sender + receiver are:

- Web browser/server for e-transactions + clients,

- Online banking server + clients

- DNS servers + requesting hosts,

- Routers exchanging routing table updates, and many more

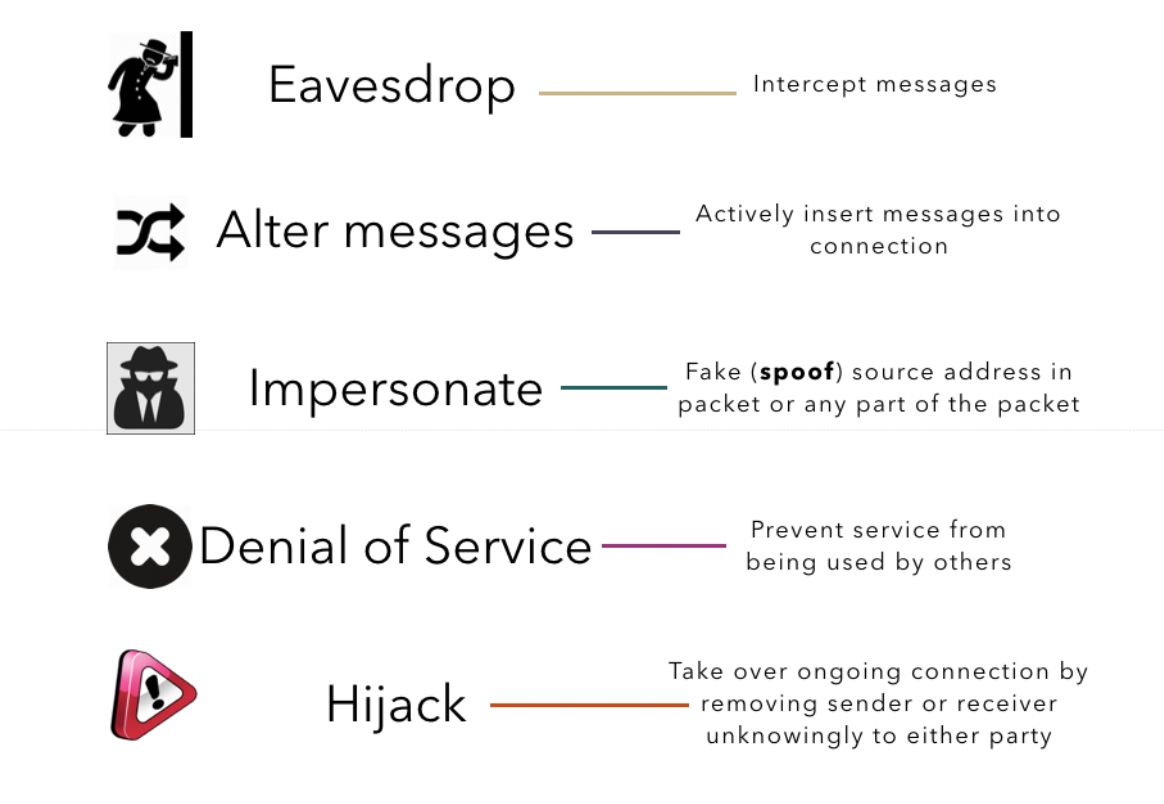

Possible Security Attacks

There are five possible security attacks that we are going to discuss in this chapter. Each of these attacks compromise specific security properties:

- Eavesdrop attack threatens confidentiality

- Message alteration attack threatens integrity

- Impersonation threatens authentication

- Hijacking threatens authentication

- Denial of Service threatens access and availability

Connection hijacking is a security breach where an intruder intercepts and takes control of an established communication session between a client and a server. This can be done in various ways, such as session fixation, session side jacking, and TCP/IP hijacking, which is not part of our syllabus. You are welcome to read this appendix section if you’d like to find out more about it.

Cryptography

Cryptography

Cryptography is the practice and study of techniques for secure communication in the presence of third parties called adversaries. It encompasses a wide range of methods for ensuring the confidentiality, integrity, authenticity, and non-repudiation of data.

The most basic way to support some of these security properties is via encryption. For example, encrypting your messages ensures confidentiality, as attackers are unable to understand your message / eavesdrop if good encryption algorithms are applied.

How can Messages be Encrypted?

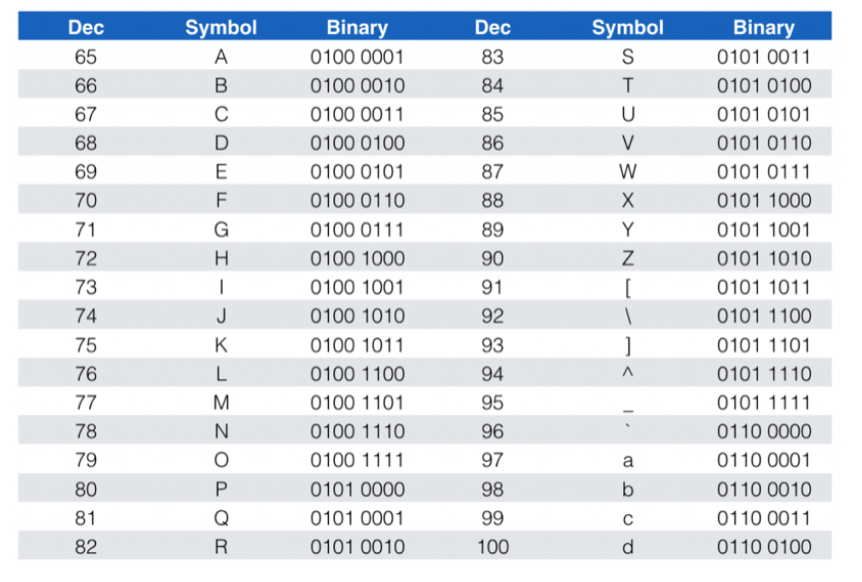

Suppose you have a confidential word document, image, music, videos, executables, etc. They’re stored in terms of binary data in the tertiary storage. Depending on their encoding format, our computer is able to translate these encoded bit patterns to the humanly understandable output you see on your screen, e.g we can read the contents of a text file using UTF-u encoding:

In short, you can treat a message (e.g: plaintext, image, anything) like series of integers (simple binary to dec translation).

Encrypting a simple text message is equivalent to encrypting a number, which means that we can perform mathematical operations on those numbers.

The ciphertext (resulting encrypted value) will not be decodable anymore (which is the point!) until we decrypt them using the right key (method). As a side note: encryption is not equivalent to encoding. Read this appendix section if you’d like to find out more.

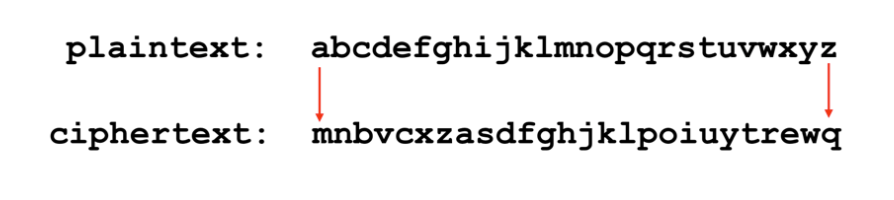

Substitution Cipher

A substitution cipher is a method of encryption where each unit of plaintext is replaced with ciphertext according to a fixed system.

A naive attempt to encrypt your text message is by mapping from a set of letters to another set as such:

Main disadvantage

The frequency of the letters are not masked at all. Once you have deciphered some common letters, it is easy to fill in the gaps.

There are also other forms of substitution ciphers, some of which are still used today but the context is out of our syllabus. You can head to appendix to find out more.

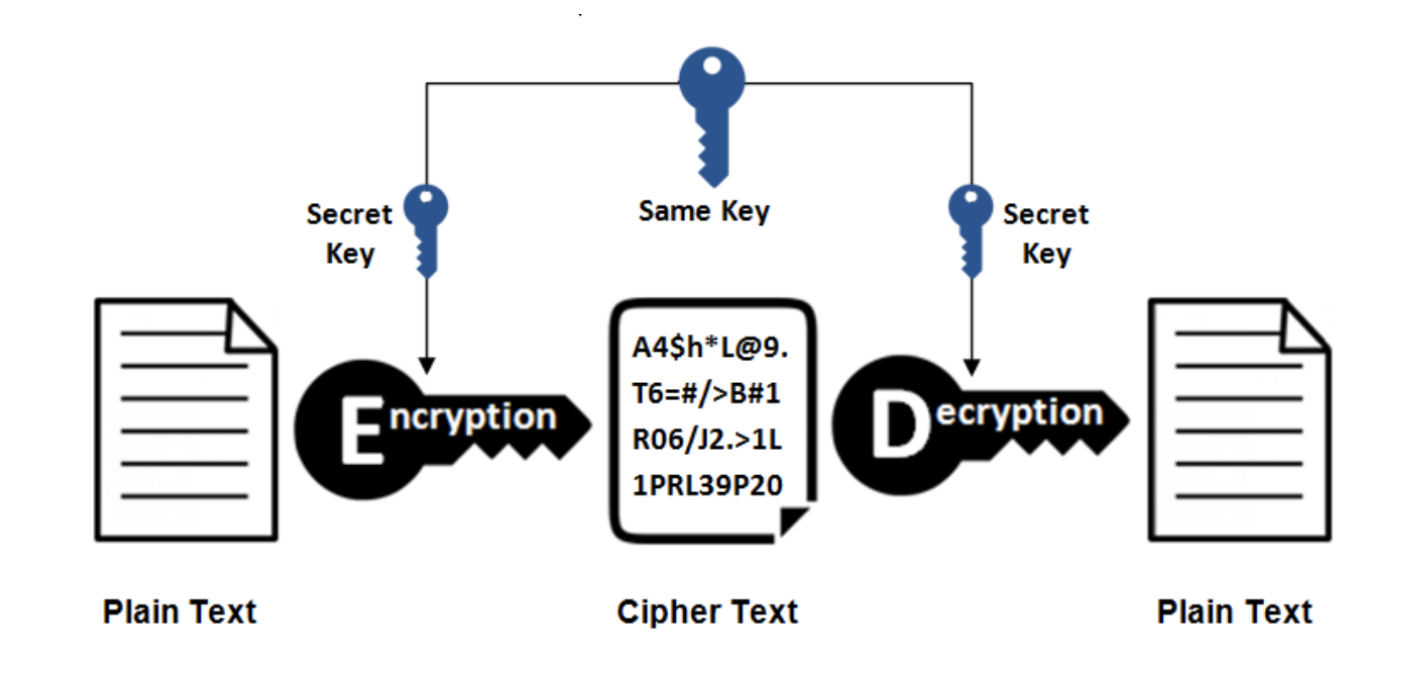

Symmetric Key Cryptography

Symmetric key cryptography is a type of encryption where the same key is used for both encrypting and decrypting the data.

Sender and receiver can encrypt plain text and decrypt ciphertext with the same key. In short, any plaintext can be converted into bits (e.g: with UTF8 encoding, ASCII encoding, etc). We can segment our message into bits of X bytes in length, and then generate a K bits key, and perform arithmetic operations between the two.

There are two algorithms for symmetric key encryption: DES and AES.

Main Disadvantage

Need to find a way to share the key first (best if shared in person).

Data Encryption Standard (DES)

Details about DES are summarised as follows:

- An algorithm to perform symmetric key cryptography

- 56-bit symmetric key is used

- 64-bit plaintext input is required (padding may be needed). If input size is longer than 64 bits, they need to be chopped into blocks of 64 bits.

- The final block that does not amount to 64 bits will need to be padded to form 64 bits.

- There might be some protocol variant that add probabilistic padding for each block, but the details are out of this syllabus.

- 16 identical rounds of encryption to produce 64-bit encrypted output

- It was US encryption standard in 1993

- Can be decrypted using brute force in less than a day using modern computing power

The figure below illustrates how the algorithm works (you are NOT required to memorize this, they’re just for illustrative purposes):

We can apply 3-DES to make encryption more secure.

3DES

3DES, also known as Triple DES, is an encryption algorithm that uses the Data Encryption Standard (DES) cipher algorithm three times to each data block. It was developed to provide a more secure alternative as DES became vulnerable to brute-force attacks due to its relatively short key length of 56 bits.

By applying the DES cipher three times to each data block, 3DES significantly increases the security of DES by extending the effective key length. The typical key length used in 3DES is 168 bits (three 56-bit DES keys), but it can also operate in modes that use two keys (112 bits total).

Despite its increased security over DES, 3DES is considerably slower than many of its modern counterparts and has begun to be phased out in favor of more advanced encryption standards, such as AES (Advanced Encryption Standard), due to AES’s greater efficiency and security.

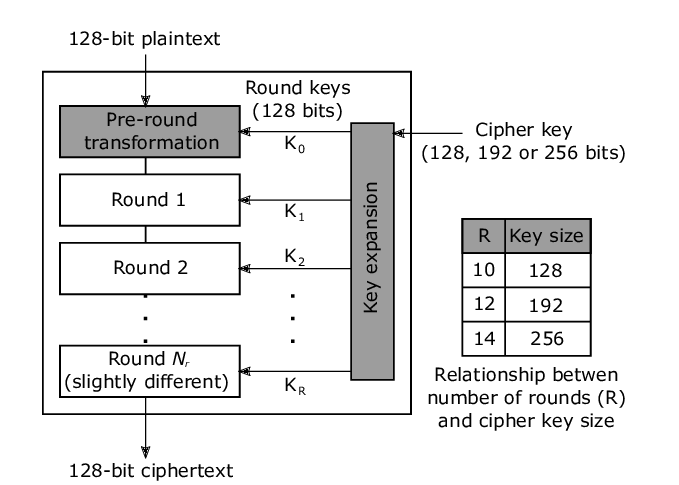

Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)

Details about AES are summarised as follows:

- AES is better algorithm to perform symmetric key cryptography as opposed to 3DES

- 128, 192, or 256-bit symmetric key is used

- 128-bit plaintext input blocks are accepted

- Similarly, padding is needed for blocks < 128 bits

- 10,12,14 rounds of encryption is performed to produce 128-bit encrypted output

- AES replaced DES in 2001,

- If a 128-bit key is used, brute force decryption will take 1 billion billion years (yes, double billions) even with a supercomputer

- However it can take much faster with a Quantum computer

The figure below illustrates how the algorithm works (you are NOT required to memorize this, they’re just for illustrative purposes):

Asymmetric Key Cryptography

Asymmetric key cryptography, also known as public key cryptography, is an encryption method that uses a pair of keys for secure communication: a public key, which can be shared with everyone, and a private key, which is kept secret by the owner.

This method enables not only secure encryption but also digital signatures and key exchanges (see later sections).

RSA

RSA (Rivest–Shamir–Adleman) is one of the first public-key cryptosystems and is widely used for secure data transmission. Invented in 1977 by Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman, it remains an important element in digital security and is used in a variety of applications like SSL/TLS for securing websites and digital signatures:

Characteristics:

- Sender, receiver, do not need to pre-share secret key prior to communication

- Public encryption key known to all

- Private decryption key known only to receiver

- 1024 - 4096-bit asymmetric (public-private) key pair generated

- 1 round of encryption required

- Input/output size: depends on key size and padding

The RSA fulfils two important requirements of Asymmetric Key Cryptography:

- Given the public key, it is impossible to compute the private key

- This ensures the security of the cryptographic system. The public key can be widely distributed without compromising the private key.

- The difficulty of deriving the private key from the public key is based on hard mathematical problems, such as factoring large prime numbers (RSA) or solving discrete logarithms (Elliptic Curve Cryptography).

- Able to produce a public-private key pair such that,

encrypt(message, public_key) = ciphertext(encryption)decrypt(ciphertext, private_key) = message(decryption)- This ensures that messages encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted with the corresponding private key, providing confidentiality.

Note that the opposite can also be done:

encrypt(message, private_key) = signed_ciphertext(signing)decrypt(signed_ciphertext, public key) = message(verification)- This ensures that a message signed with the private key can be verified by anyone with the public key, providing authenticity and integrity. This operation is typically referred to as signing rather than encrypting with the private key, and verifying rather than decrypting with the public key.

How RSA Works

RSA involves a set of algorithms for key generation, encryption, and decryption:

- Key Generation:

- Choose two large prime numbers, \(p\) and \(q\).

- The prime numbers \(p\) and \(q\) are chosen such that when multiplied together, they yield a product \(n\) with the desired key length.

- For example, for a 2048-bit RSA key, each prime \(p\) and \(q\) would typically be around

1024bits in size.

- Compute \(n = p \times q\). The value \(n\) is used as the modulus for both the public and private keys. Its length, usually expressed in bits, is the key length.

- Calculate \(z = \phi(n) = (p-1) \times (q-1)\).

- \(\phi\) is known as Euler’s totient function (see appendix for more details).

- Choose an integer \(e\) such that \(1 < e < z\) and \(e\) is coprime to \(z\).

- This \(e\) will be the public exponent.

- Determine \(d\) as the modular multiplicative inverse of \(e \bmod z\), that is solve \(d\) such that \((ed) \bmod z = 1\).

- This can be calculated using the Extended Euclidean Algorithm (out of syllabus, see Appendix to find out more).

- This \(d\) is the private exponent.

- Choose two large prime numbers, \(p\) and \(q\).

- Public Key and Private Key:

- The public key is made of the pair \((n, e)\).

- The private key consists of \((n, d)\).

- Encryption:

- Given a plaintext message \(M\), the ciphertext \(C\) is computed as \(C = M^e \bmod n\), using the public key.

- Decryption:

- Using the private key, the original message \(M\) is recovered by computing \(M = C^d \bmod n\), using the private key.

- Signing:

- Using the private key, the digital signature \(S\) is computed as \(S = M^d \bmod n\), using the private key.

- Verification:

- To verify a given digital signature \(S\), we can compute \(M = S^e \bmod n\), using the public key.

Coprime

Two integers are said to be “relatively prime” (also known as “coprime” or “mutually prime”) if they have no common positive factors other than 1. In other words, their greatest common divisor (GCD) is 1. This concept is crucial in various fields of mathematics and cryptography, particularly in algorithms involving modular arithmetic.

Example: the numbers 12 and 13 are relatively prime because 12 is divisible by 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 12 and 13 is divisible by 1 and 13, with their only common divisor being 1.

A Simple Example

Let’s shoose 2 prime numbers (small, for illustration purposes), \(p=61\), \(q=53\).

We can compute: \(n=p \times q =3233\), \(z=60 \times 52 = 3120\). Choose \(e=17\) since \(e<z\) and both \(e=17\) and \(z=60\) are relatively prime (coprime). Then, calculate \(d\) such that \((d*17) \bmod 3120 = 1\).

One possible value for \(d\) is \(2753\).

Hence:

- Public key is \((3233, 17)\)

- Private key is \((3233, 2753)\)

Let’s say we have m=01000001 (the letter ‘A’ in UTF-8 encoding). This corresponds to 65 in decimal.

- Encryption: \(c = 65^{17} \bmod 3233 = 2790\)

- Decryption: \(m = 2790^{2753} \bmod 3233 = 65\) (original value)

Message Segmentation

Messages that are long will be separated into segments such that the size of these segments is less than n.

This segmentation ensures that the message can be encrypted and decrypted correctly using modular exponentiation modulo \(n\).

The typical approach is to break the message into fixed-size blocks and then encrypt each block individually using RSA encryption. The size of the blocks depends on the size of the modulus \(n\) and the desired security level. You will know more about this during the lab and PA2.

For example, if you have a 2048-bit RSA key, the modulus \(n\) would be a 2048-bit number. In this case, you would typically break the plaintext message into smaller blocks that are significantly smaller than 2048 bits, ensuring that each block is less than \(n\) in value.

- After encrypting each block separately, you can concatenate the ciphertext blocks together to form the final encrypted message.

- During decryption, the same process is applied in reverse. Each ciphertext block is decrypted separately using modular exponentiation modulo \(n\), and then the decrypted blocks are concatenated together to recover the original plaintext message.

Segmenting the message into smaller blocks ensures that RSA encryption and decryption can be performed efficiently and correctly, even for long messages.

Conceptual Differences: Encryption vs Signing

Encryption: The primary goal is confidentiality. Encryption with a public key ensures that only the holder of the corresponding private key can decrypt and read the message. Signing: The primary goals are authenticity and integrity. Signing with a private key allows anyone with the public key to verify who sent the message and that it has not been altered.

Security of RSA

The security of RSA relies on the practical difficulty of factoring the product of two large prime numbers, the factoring problem. The larger the key size, the more secure the RSA system, although this also increases computational overhead. Common key lengths are 2048 and 4096 bits.

Practical Uses

Secure communications: RSA can be used to encrypt data transmissions or to secure sensitive data by encrypting it with a public key, ensuring that only the holder of the private key can decrypt it. Digital Signatures: RSA is also used for digital signatures, where a message is signed with a sender’s private key and can be verified by anyone who has access to the sender’s public key.

Since public key \((n, e)\) is known to everybody and private key \((n, d)\) is only known to receiver, an attacker only need to guess the value of \(d\) to decrypt the message:

- \(e\) is known and \(d\) is related to \(e\), \((ed-1) mod z = 0\)

- To find \(z\), one has to know \(p\) and \(q\)

- \(p\) and \(q\) is related to \(n\), \(n = p*q\)

Hence, one has to be able to perform prime factorization of \(n\) to guess \(p\) and \(q\) correctly. If \(n\) is sufficiently large, e.g: 1024 bits, it is hard to find the correct prime factors of \(n\) (exponential complexity). To crack a simple 128-bit key, a supercomputer (in 2022) on estimate, requires ~10^(39) seconds. The universe is younger than that.

The prime factorization problem falls under NP problem

RSA has stood the test of time, remaining robust against various attacks when correctly implemented and used with a sufficient key size. However, in the era of quantum computing, RSA’s security could potentially be compromised, leading to interest in developing quantum-resistant algorithms.

Practical Issues

RSA requires exponentiation of very large numbers. This is computationally exhaustive. In comparison, DES is 100x faster than RSA.

One solution is to use session key.

Session Key

We use public-key cryptography to establish a secure connection, meaning that we authenticate (the identity of) our host. Then, one party will generate symmetric session key and exchange between sender and receiver using public-key cryptography.

We then use this symmetric session key (instead of the public key) for the subsequent message exchanges throughout the session. See the next chapter for further details.

Summary

In this chapter on Network Security and Cryptography, we delve into the crucial properties essential for secure communication over the internet: Confidentiality, Integrity, Authentication, and Access/Availability. We explore various threats to these properties and strategies to mitigate them. Here’s a breakdown of key concepts covered:

- Security Properties:

- Confidentiality ensures only authorized parties can access message contents.

- Integrity ensures messages remain unaltered during transit.

- Authentication verifies the identities of communicating parties.

- Access and Availability ensure internet services are accessible and operational.

- Possible Security Attacks:

- Eavesdrop, Message Alteration, Impersonation, Hijacking, and Denial of Service attacks compromise specific security properties.

- Cryptography:

- Cryptography encompasses techniques for secure communication, focusing on confidentiality, integrity, authenticity, and non-repudiation of data.

- Encryption plays a fundamental role in achieving these goals.

- Symmetric Key Cryptography:

- Utilizes the same key for both encryption and decryption.

- Algorithms like DES and AES are prominent examples, with AES being more secure and efficient.

- Asymmetric Key Cryptography:

- Uses a pair of keys (public and private) for secure communication.

- RSA is a widely used asymmetric key algorithm, facilitating secure data transmission, digital signatures, and key exchanges.

- RSA Algorithm:

- Involves key generation, encryption, decryption, signing, and verification.

- Security relies on the practical difficulty of factoring large prime numbers.

- RSA’s robustness stands against various attacks, although quantum computing poses potential threats.

- Practical Considerations:

- RSA’s computational intensity compared to symmetric key algorithms like DES.

- Session keys offer a solution for improving efficiency in message exchanges.

In conclusion, understanding network security and cryptography principles is imperative for maintaining secure communication channels, ensuring data confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity in an interconnected world. While RSA remains a stalwart in cryptographic practices, ongoing advancements and emerging technologies necessitate continuous evolution in security measures.

Appendix

Cryptography vs Encoding

Encoding and cryptography are both methods used to manipulate data, but they serve different purposes and operate under different principles.

Encoding:

-

Purpose: Encoding is used to transform data into a different format or representation that is more suitable for specific applications, such as data storage, transfer, or display. It ensures that data remains intact and interpretable by different systems and software.

-

Examples: Common encoding schemes include ASCII for text representation, UTF-8 for universal text encoding that includes a wide array of characters from different languages, Base64 for encoding binary data into ASCII characters, and MIME types for describing media types in email and web documents.

-

Reversibility: Encoded data can be easily converted back to its original form without any loss of information, using the same or a corresponding decoding process.

-

Security: Encoding does not provide security. It’s not intended to hide information or protect it from unauthorized access. It’s meant for compatibility and interoperability between different systems.

Cryptography:

-

Purpose: Cryptography is primarily used for securing data against unauthorized access. It involves techniques to encrypt data, making it unreadable to anyone who does not have the decryption key.

-

Examples: Cryptographic methods include symmetric key algorithms (like AES and DES), asymmetric key algorithms (such as RSA), and hash functions (like SHA-256).

-

Reversibility: For encryption algorithms, the process is reversible only if the key is known. For hash functions, the process is designed to be irreversible, providing a way to verify data integrity without revealing the original data.

-

Security: The core goal of cryptography is to ensure data security. It provides tools for confidentiality (keeping data secret), integrity (preventing data alteration), authentication (verifying identity), and non-repudiation (preventing denial of an action).

Key Differences

- Objective: Encoding is about data representation and compatibility; cryptography is about data security.

- Reversibility: Encoding is always reversible; cryptography can be reversible or irreversible depending on the technique.

- Complexity: Cryptography generally involves complex algorithms that require keys for encryption and decryption, while encoding uses simpler schemes.

- Usage: Encoding is used everywhere data needs to be formatted or transformed; cryptography is used when data needs to be secured against unauthorized access or tampering.

In summary, while both encoding and cryptography involve altering the original data form, encoding is meant for maintaining data usability and interoperability, whereas cryptography focuses on securing data from unauthorized access and ensuring its integrity and authenticity.

Cryptography vs Hashing

Hashing is indeed often discussed separately from encryption, but it is considered a crucial part of the broader field of cryptography. Let’s explore hashing in detail:

What is Hashing?

As you’ve learned from 50.004, hashing is the process of using a hash function to convert an input (or ‘message’) of any length into a fixed size string of bytes, which we call a digest that represents the original string. The output, known as the hash value or hash digest, is typically much shorter than the input.

Characteristics of Hash Functions

- Deterministic: The same input will always produce the same output.

- Fixed Output Length: Regardless of the input size, the output (hash) has a fixed length.

- Efficiency: The function should be able to return the hash value quickly.

- Pre-image Resistance: Given a hash output, it should be computationally infeasible to reconstruct the original input.

- Small Changes Lead to Large Differences: Even a small change in the input should result in a significantly different output. This is often referred to as the avalanche effect.

- Collision Resistance: It should be hard to find two different inputs that produce the same output hash.

Hashing vs. Encryption

- Purpose: Encryption is meant for data security, specifically to keep data confidential. Hash functions, however, are used for integrity checks, data indexing, and quick retrieval of data in databases and other data structures.

- Reversibility: Encryption is designed to be reversible (decrypted) using a key, while hashing is a one-way function and is not meant to be reversible.

- Use Cases: Encryption is used when data needs to be hidden and securely transmitted or stored. Hashing is used for creating digital signatures, verifying the integrity of data, and ensuring data has not been altered (tamper evidence).

Not Cryptography?

While hashing is not used for concealing data (as traditional encryption is), it is still considered a part of cryptography because it deals with the principles of data security, specifically integrity and authenticity. It’s a fundamental tool in the cryptographic toolbox, used to support encryption and digital signatures, ensure data integrity, and authenticate information or identities.

However, a hash function as a method of encryption is not appropriate or effective for several reasons. Here’s why:

-

One-way Operation: Hash functions are designed to be one-way functions, meaning they are intended to be irreversible. Once data is transformed into a hash, it cannot be transformed back into the original data using the hash alone. Encryption, on the other hand, requires the data to be reversible, allowing the original information to be retrieved (decrypted) using a key.

-

Fixed Output Length: Hash functions produce a fixed-length output regardless of the input size. This characteristic means that the output does not retain all the original information if the input varies significantly in size, which is a necessary capability for encryption algorithms.

-

No Key Usage: Hash functions do not use keys. Encryption relies on keys to encode and decode data securely. The use of keys in encryption allows only those with the correct key to access the original data, providing confidentiality and security.

-

Lack of Confidentiality: Since hash functions are deterministic (the same input always produces the same output) and widely known, they do not provide confidentiality. Anyone with access to the hash function and the output can check guesses about the input. In encryption, even if the algorithm is known, the data is protected by the secrecy of the key.

Alternative Uses of Hash Functions in Security

While hash functions themselves are not suitable for encryption, they are crucial in other security applications:

- Integrity Checks: Hash functions can verify that data has not been altered by comparing a previously stored hash to a newly computed hash of the data.

- Password Storage: Hashes are used to store passwords securely. Instead of storing the password itself, systems store a hash of the password. During authentication, the system hashes the password input by the user and compares it to the stored hash.

- Digital Signatures: Hash functions are used in digital signatures. The data is hashed, and then the hash is encrypted with a private key, creating a signature that verifies the data’s integrity and origin.

In summary, while hash functions are invaluable for certain security measures, their characteristics make them unsuitable for use as encryption tools. Encryption and hashing serve different purposes in the realm of data security.

Thus, while distinct from encryption, hashing is a cryptographic process because it helps protect information and systems in a complementary manner to encryption and other cryptographic techniques.

Further Information About Substitution Cipher

A substitution cipher is a method of encryption by which units of plaintext are replaced with ciphertext according to a fixed system; the “units” may be single letters (the most common), pairs of letters, triplets of letters, mixtures of the above, and so forth. The receiver deciphers the text by performing the inverse substitution.

Types of Substitution Ciphers

-

Simple Substitution Cipher: Each letter of the plaintext is replaced by a letter with some fixed relationship to it. For example, in a Caesar cipher, each letter in the plaintext is shifted a certain number of places down or up the alphabet. If the shift is 3, then A would be replaced by D, B by E, and so on.

-

Homophonic Substitution Cipher: This type extends the basic substitution cipher by allowing multiple possible ciphertexts for a single letter. For example, ‘A’ might be replaced by any of the symbols ‘@’, ‘%’, or ‘#’. This makes cryptanalysis more difficult.

-

Polyalphabetic Substitution Cipher: Using multiple cipher alphabets, the substitution changes during the encryption process. The Vigenère cipher is a well-known example where the shift in the alphabet is determined by a repeating keyword.

-

Polygraphic Substitution Cipher: Instead of substituting individual letters, this cipher substitutes blocks of letters. The Playfair cipher, for example, encrypts digraphs (two-letter blocks), making it significantly harder to crack compared to simple substitution ciphers.

How Substitution Ciphers Work

To encrypt a message using a basic substitution cipher, you would follow these steps:

-

Choose or generate a secret key: In a Caesar cipher, the key is the number of positions each letter should be shifted. In more complex systems, the key might be a word or phrase that dictates the substitution pattern.

-

Apply the cipher: Based on the key, substitute each letter of the plaintext with the corresponding letter in the ciphertext alphabet.

-

Send the encrypted message: The receiver, who knows the key and the substitution method, can reverse the process to decrypt the message.

Security of Substitution Ciphers

Substitution ciphers are generally not very secure when used alone in modern times due to the following vulnerabilities:

- Frequency Analysis: Many languages have a predictable frequency of letters (e.g., ‘E’ is the most common letter in English). By analyzing the frequency of characters in the ciphertext, an attacker can guess the substitution based on statistical models of the language.

- Known Plaintext Attacks: If an attacker knows or can guess parts of the plaintext, they can deduce other elements of the cipher.

- Limited Keyspace: Especially in simple substitution ciphers, the number of possible keys is finite and not extremely large, which makes brute-force attacks feasible.

Despite these vulnerabilities, substitution ciphers played a crucial role in the history of cryptography and laid the groundwork for more complex encryption methods used today. They are still used in various forms, often as components of more complex encryption systems where they contribute to overall security.

Euler’s Totient Function

Euler’s totient function, often denoted as \(\phi(n)\), is a mathematical function that counts the number of integers up to \(n\) that are relatively prime to \(n\). In other words, it calculates the number of integers from 1 to \(n\) inclusive that do not share any common factors with \(n\) other than 1.

Calculation

The value of \(\phi(n)\) can be calculated in different ways depending on the nature of \(n\):

- If \(n\) is a prime number: \(\phi(n) = n - 1\). This is because a prime number does not have any divisors other than 1 and itself, so all numbers less than \(n\) are relatively prime to \(n\).

- If \(n\) is a product of two distinct prime numbers \(p\) and \(q\): \(\phi(n) = (p - 1)(q - 1)\). This formula comes from the fact that the only numbers not relatively prime to \(n\) are the multiples of \(p\) and \(q\), excluding the overlap (which is the number \(pq\) itself).

- More generally, if \(n\) is the product of prime powers: \(n = p_1^{k_1} p_2^{k_2} \ldots p_m^{k_m}\), then \(\phi(n) = n \left(1 - \frac{1}{p_1}\right) \left(1 - \frac{1}{p_2}\right) \ldots \left(1 - \frac{1}{p_m}\right)\).

Importance in Cryptography

Euler’s totient function is critical in cryptography, especially in the RSA encryption algorithm. It is used to:

- Determine the public exponent \(e\): In RSA, \(e\) must be chosen such that \(1 < e < \phi(n)\) and \(e\) and \(\phi(n)\) are coprime.

- Calculate the private exponent \(d\): The private key \(d\) in RSA is calculated as the modular multiplicative inverse of \(e\) modulo \(\phi(n)\), meaning \(d\) is the number such that \(ed \equiv 1 \bmod \phi(n)\).

Congruence

Equivalence (congruence \(\equiv\)) does not mean equality. \(a \equiv b \bmod n\) if the difference \(a - b\) is divisible by \(n\).

This function allows for the creation of a public and a private key in RSA that work with modular arithmetic to enable secure encryption and decryption processes.

The Extended Eucledian Algorithm

The Extended Euclidean Algorithm is an extension of the Euclidean Algorithm, which is used to find the greatest common divisor (GCD) of two integers. The Extended Euclidean Algorithm not only finds the GCD of two numbers but also finds the coefficients of Bézout’s identity, which are used to express the GCD as a linear combination of the two numbers.

In the context of RSA, the Extended Euclidean Algorithm is used to find the modular multiplicative inverse of two numbers modulo \(\phi(n)\). This modular inverse is required to compute the private exponent \(d\) such that \((d \times e) \bmod \phi(n) = 1\).

Here’s how the Extended Euclidean Algorithm works:

Given two non-negative integers \(a\) and \(b\) such that \(a \geq b\), the algorithm finds integers \(x\) and \(y\) such that \(ax + by = \text{gcd}(a, b)\).

The algorithm iteratively performs division with remainder until the remainder becomes zero. At each step, it updates the values of \(x\), \(y\), \(a\), and \(b\) accordingly.

Here’s a high-level overview of the algorithm:

- Initialize \(x_0 = 1\), \(y_0 = 0\), \(x_1 = 0\), \(y_1 = 1\), \(a_0 = a\), and \(b_0 = b\).

- Until \(b_i\) becomes zero, repeat the following steps:

- Compute the quotient \(q_i\) and remainder \(r_i\) when dividing \(a_i\) by \(b_i\).

- Update \(x_{i+1} = x_{i-1} - q_i \times x_i\) and \(y_{i+1} = y_{i-1} - q_i \times y_i\).

- Update \(a_{i+1} = b_i\) and \(b_{i+1} = r_i\).

- The last non-zero remainder \(r_k\) is the GCD of \(a\) and \(b\).

- The coefficients \(x_k\) and \(y_k\) represent the Bézout coefficients, such that \(ax_k + by_k = \text{gcd}(a, b)\).

Once the Extended Euclidean Algorithm finds the GCD and the coefficients, the modular inverse of \(e\) modulo \(\phi(n)\) can be computed. This modular inverse is the private exponent \(d\) needed for RSA encryption and decryption.

RSA Proof of Correctness

To understand the math behind RSA, you need to know the following modular arithmetic properties:

- Addition and subtraction modulo: \([(a \bmod n) \pm (b \bmod n)]\) \(\bmod n\) \(= (a \pm b) mod n\)

- Multiplication modulo: \([(a \bmod n) \times (b \bmod n)]\) \(\bmod n\) \(= (a \times b) mod n\)

- Exponentiation modulo: \([(a \bmod n)^d] \bmod n\) \(= a^d \bmod n\)

Then, in order to prove that RSA is correct, two more important properties are required:

- If \(k = m^d \bmod n\) and \(m = c^d \bmod n\), then \(k^e \bmod n = m\).

- \(x^y \bmod n = x^{y \bmod z} \bmod n\) for any \(x,y\) where \(n = pq\), \(z = (p-1)(q-1)\) and \(gcd(x,n) = 1\), that is n is coprime with x. This can be proved by deduction.

The second expression can be used to find equivalence (congruence \(\equiv\)) of x^y mod n as long as gcd(x,n) = 1, with smaller values of y to speed up computation.

Let’s go through the deduction:

- Initial Observation:

- The Euler’s theorem states that if \(x\) and \(n\) are coprime (i.e., \(\text{gcd}(x, n) = 1\)), then \(x^{\phi(n)} \equiv 1 \bmod n\), where \(\phi(n)\) is Euler’s totient function.

- If \(n = pq\) and \(z = (p-1)(q-1)\), then \(\phi(n) = (p-1)(q-1) = z\).

- Substitute:

- Given \(x^y \bmod n\), we can substitute \(y\) as \(y = qk + r\) where \(k\) is an integer quotient and \(r = y \bmod q\). This is due to the fact that \(y\) can be expressed as a multiple of \(q\) plus a remainder.

- Substitute \(y\) into the expression: \(x^y \bmod n = x^{(qk + r)} \bmod n\).

- Using Euler’s Theorem:

- Since \(x\) and \(n\) are coprime, we can apply Euler’s theorem: \(x^{\phi(n)} \equiv 1 \bmod n\).

- Therefore, \(x^z \equiv 1 \bmod n\), where \(z = (p-1)(q-1)\).

- Further Substitution:

- Substitute \(x^{(qk + r)} \bmod n\) as \(x^{(qk + r) \bmod z} \bmod n\) since \(x^z \equiv 1 \bmod n\) (powers of x mod n repeats every z)

- So, \(x^{(qk + r)} \bmod n = x^{(qk + r) \bmod z} \bmod n\).

- Conclusion:

- This proves that \(x^y \bmod n = x^{y \bmod z} \bmod n\) for any \(x, y\) where \(n = pq\) and \(z = (p-1)(q-1)\) and \(gcd(x,n) = 1\) (x and n are coprime).

This deduction demonstrates the relationship between modular exponentiation and Euler’s theorem, which is fundamental to the RSA algorithm.

To prove the correctness of RSA, we need to demonstrate that the encryption and decryption operations are indeed inverses of each other, meaning that encrypting a message and then decrypting it using the corresponding keys will yield the original message. Here’s the proof:

- Encryption:

- Let \(m\) be the plaintext message.

- The ciphertext \(c\) is computed as \(c = m^e \bmod n\), where \(e\) is the public exponent and \(n\) is the modulus.

- Decryption:

- To decrypt the ciphertext \(c\), we compute \(m' = c^d \bmod n\), where \(d\) is the private exponent.

- Proof of Correctness:

- We need to show that \(m' = m\), i.e., the original message is recovered after decryption.

Let’s verify this:

\[\begin{align*} c^d \bmod n &= (m^e)^d \bmod n \\ &= m^{ed} \bmod n \\ &= m^{k\phi(n) + 1} \bmod n \quad (\text{where } k \text{ is an integer}) \\ &= (m^{\phi(n)})^k \cdot m \bmod n \\ & (\text{by Euler's theorem (see below): } m^{\phi(n)} \equiv 1 \bmod n) \\ &= 1^k \cdot m \bmod n \\ &= m \bmod n \end{align*}\]Thus, \(m' = m\), demonstrating that decryption indeed recovers the original message.

This proof shows that RSA encryption and decryption work correctly under the assumption that the private and public keys are generated properly and securely. It also assumes that the security of RSA relies on the difficulty of factoring the modulus \(n\).

Euler’s Theorem

Euler’s theorem provides a crucial relationship between exponentiation and modular arithmetic. It states that if \(a\) and \(n\) are coprime integers (i.e., they have no common factors other than 1), then \(a^{\phi(n)} \equiv 1 \bmod n\), where \(\phi(n)\) is Euler’s totient function.

To understand why \(a^{\phi(n)} \equiv 1 \bmod n\), we can break it down into a few steps:

- Coprime Property:

- If \(a\) and \(n\) are coprime, it means that they have no common factors other than 1. This property is essential for Euler’s theorem to hold.

- Grouping Residues:

- When considering the residues of \(a^k\) modulo \(n\) for \(k = 1, 2, 3, ...\), they form a cycle. Eventually, the cycle will repeat because there are only a finite number of possible residues modulo \(n\).

- Cycle Length:

- Euler’s totient function, \(\phi(n)\), gives the number of positive integers less than \(n\) that are coprime to \(n\). This value also represents the length of the cycle formed by the residues of \(a^k\) modulo \(n\).

- Residue 1:

- Because of the cyclical nature of residues, \(a^{\phi(n)}\) will produce the same residue as \(a^0 = 1\) modulo \(n\). In other words, \(a^{\phi(n)}\) “wraps around” to produce the residue 1 modulo \(n\).

- Modular Congruence:

- Since \(a^{\phi(n)}\) produces the same residue as 1 modulo \(n\), we can express this as \(a^{\phi(n)} \equiv 1 \bmod n\).

Thus, Euler’s theorem establishes that when \(a\) and \(n\) are coprime, \(a^{\phi(n)}\) is congruent to 1 modulo \(n\). This property is fundamental in RSA cryptography, as it forms the basis for correctness and security in the RSA algorithm.

Connection Hijacking

Connection hijacking is when an intruder takes control of an active communication session between a client and a server. Let’s break down what happens when an intruder hijacks a connection:

- TCP/IP Hijacking:

- Initial Setup: The client establishes a connection with the server, and they start communicating. Each packet sent between them contains sequence numbers.

- Intruder’s Actions: The intruder intercepts the communication stream and starts injecting malicious packets. The intruder needs to predict or know the sequence numbers to successfully inject packets that will be accepted by the client.

- Behavior of True Packets:

- True Server Packets: If the intruder hijacks the connection and starts sending data to the client, the true server’s packets will still be sent to the client unless the intruder also disrupts the server’s ability to communicate.

- Client Receiving Packets: The client may receive packets from both the true server and the intruder. However, due to how TCP/IP handles sequence numbers and acknowledgments, the client’s behavior can vary:

- If the sequence numbers from the intruder match the expected sequence numbers of the client’s TCP stack, the client will accept the intruder’s packets and potentially discard out-of-order packets from the true server.

- If the sequence numbers from the true server and the intruder are out of sync, the client may experience duplicate or out-of-order packets, leading to confusion and potential errors.

- Handling Duplicate Packets:

- TCP Stack Mechanism: TCP has mechanisms to handle duplicate and out-of-order packets. It uses sequence numbers and acknowledgments to determine the correct order of packets.

- Intruder’s Goal: A successful hijack involves the intruder sending packets with the correct sequence numbers, making the client believe the packets are coming from the true server. The client will acknowledge these packets, and if the server is not aware of the hijack, it may continue to send packets, which could be considered out of order or duplicates by the client’s TCP stack.

- Client’s Experience:

- The client might receive responses from both the intruder and the true server if the intruder does not completely block the server’s packets.

- The client may discard packets from the true server if the intruder’s packets are considered valid by the client’s TCP stack.

- There can be a disruption in the session, leading to confusion, errors, or dropped connections.

Example Scenario

Let’s clarify how connection hijacking works with a concise example. Suppose we have:

- Client (C) is communicating with Server (S) over a TCP connection.

- Intruder (I) wants to hijack this connection.

Steps

- Initial Communication:

- C sends data to S: “Hello, Server!”

- S responds: “Hello, Client!”

- Intruder Intercepts:

- I intercepts the communication.

- I predicts the sequence numbers being used between C and S.

- Intruder Hijacks:

- I starts sending packets to C, pretending to be S.

- Example: I sends a packet to C: “New Data from Server” with the correct sequence number.

- Client Receives Packets:

- C receives packets from both S and I.

- If I’s packet has the expected sequence number, C accepts it as valid.

- True packets from S might still reach C, but C might discard them if they seem out of order or duplicates due to incorrect sequence numbers.

What Happens to True Packets Sent by S

- True Packets from S:

- C might receive packets from S but could discard them if they don’t match the expected sequence numbers.

- If C’s TCP stack sees these packets as out of order or duplicate, it won’t process them correctly.

Client Experience

- C may:

- Accept data from I, believing it’s from S.

- Experience disrupted communication if out-of-order packets cause confusion.

- Potentially drop the connection if the sequence numbers and acknowledgments get too out of sync.

Summary

In connection hijacking, the intruder sends packets with the correct sequence numbers to the client, causing the client to accept these as valid. True packets from the server might be ignored or cause errors if they don’t match the expected sequence order.

Connection hijacking involves intercepting and injecting malicious packets into an established communication session. The true server’s packets may still reach the client, but their handling depends on the sequence numbers and the client’s TCP stack behavior. The client might receive duplicate packets, out-of-order packets, or be tricked into accepting the intruder’s packets as valid, disrupting the normal communication with the true server.

50.005 CSE

50.005 CSE