- Socket

- Socket API

- Multiplexing and Demultiplexing

- Transport Layer Protocols

- Summary

- Appendix

50.005 Computer System Engineering

Information Systems Technology and Design

Singapore University of Technology and Design

Natalie Agus (Summer 2025)

Application Layer

Detailed Learning Objectives

- Explain the Role for Application Layer Services

- Define the role and functions of the application layer in the OSI model.

- Explain how the application layer interacts with the transport layer.

- Explain Sockets in a Computer System

- Define what a socket is and its purpose in network communication.

- Derive connections with how socket (message passing) is used for IPC in the first half of the syllabus

- Distinguish between stream sockets (TCP) and datagram sockets (UDP).

- Explain how sockets are used as endpoints for communication.

- List Socket Characteristics and Common

- Identify the unique identifier of a socket (IP address + Port number).

- Explain the concept of socket binding and its importance.

- Conclude that sockets are special file descriptors in UNIX systems.

- Assess the Socket API

- Explain the key functions provided by the Socket API for network communication.

- Differentiate between internet sockets and UNIX domain sockets.

- Examine Multiplexing and Demultiplexing

- Define multiplexing and demultiplexing in the context of the transport layer.

- Apply how transport layer protocols handle data from multiple sockets.

- Examine the details of various Transport Layer Protocols

- Explain the role of TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) in providing reliable, in-order byte-stream transfer.

- Describe the characteristics of UDP (User Datagram Protocol) and its use for connectionless communication.

These learning objectives are designed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the application layer, sockets, socket API, and their interactions with transport layer protocols in network communication.

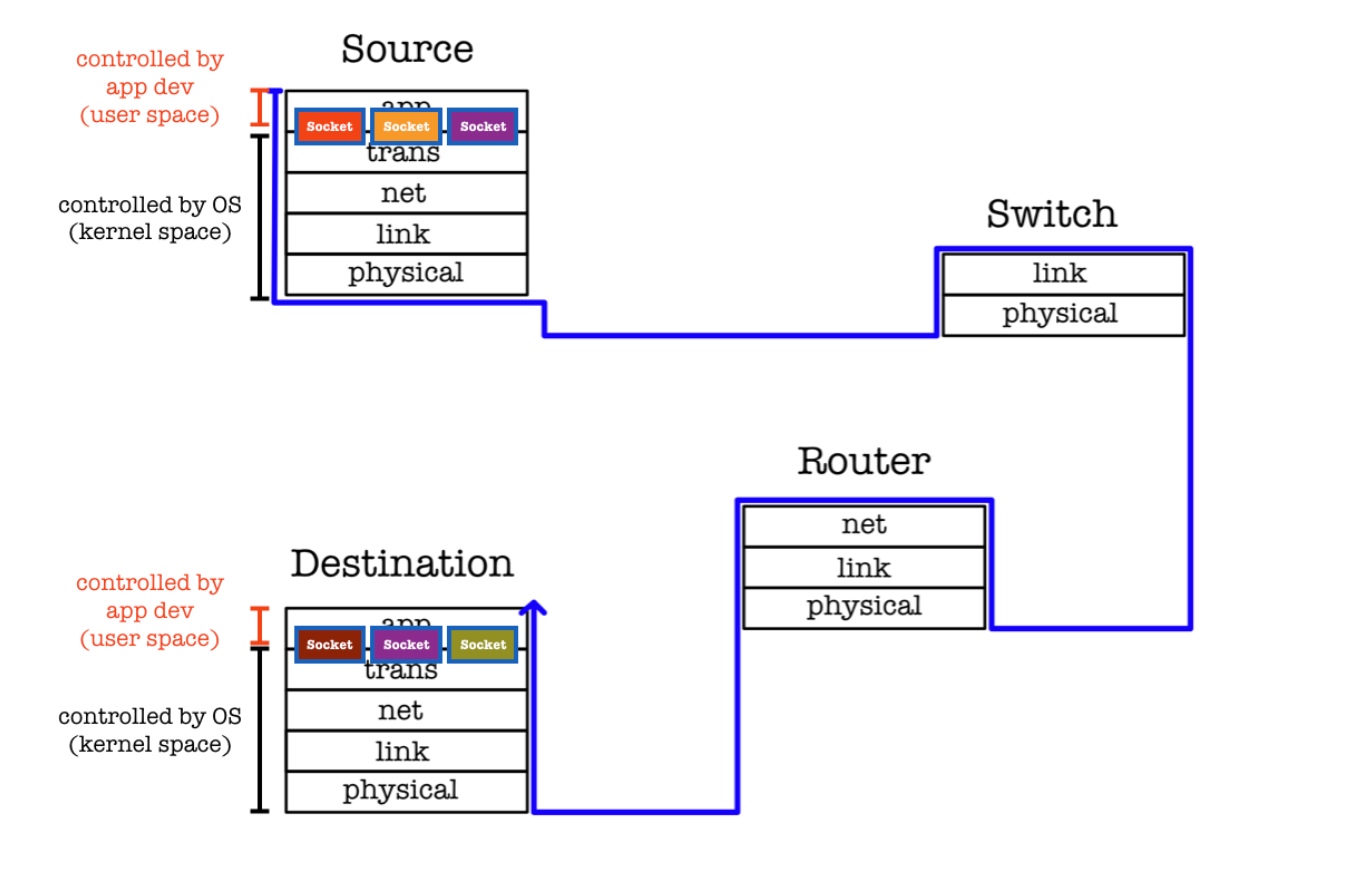

The application layer is the topmost layer in the 5-layer OSI Model of computer networking. It is responsible for providing network services directly to end-users or applications. The application layer serves as the interface between the user (or user applications) and the network, ensuring that communication between software applications on different devices is possible.

The application layer relies heavily on the transport layer to facilitate communication over the network.

Socket

Application layer programs like DNS helps to resolve domain names (web address, human readable) into IP addresses (machine readable) so that you can be found on the internet. However, your computer runs several programs at the same time. We need a way to pass the packet from the internet to the application that needs it, e.g: Steam, Web Browser, Telegram, etc.

We can name application endpoints using sockets. Network communication is a kind of I/O (just like files), and application endpoints communicate through sockets.

Socket

A socket is an endpoint for sending or receiving data across a computer network. It is a combination of an IP address and a port number, which together identify a specific process on a specific machine.

Sockets serve as the programming interface between the application layer and the transport layer. They provide a mechanism for applications to send and receive data over the network using the services provided by the transport layer.

There are two types of sockets:

- Stream Sockets (TCP): Used for connection-oriented communication. They provide reliable, ordered, and error-checked delivery of data.

- Datagram Sockets (UDP): Used for connectionless communication. They provide a faster, but less reliable, delivery of data without guaranteeing order or error-checking.

Please head to the appendix if you need a refresher about Transport Layer services.

From the diagram above, you can see that a socket is like a door between application process and end-end transport layer protocol.

Characteristics

Recall from the first half of our course that socket is one of the ways to support interprocess communication. A socket is one endpoint of a two-way communication link between two programs running on the network with the help of the kernel.

A single socket connection typically facilitates communication between two processes, but we may also enable socket sharing to enable communication among multiple processes (out of syllabus).

A socket has a unique identifier: IP address + PORT number, made up of 16 bit unsigned integer. We typically use internet sockets (used for network communication). There are also file sockets, but the details is out of syllabus. Socket is an application layer protocol. Note that IP is network layer protocol. You cannot create two sockets with the same identifier.

A socket is associated with an application. An application has to bind and listen to the socket.

Socket binding

Socket binding is the process of associating a socket with a specific IP address and port number on a host. Read the appendix to find out more about socket binding if you’re interested.

In UNIX system, a socket is a special kind of file descriptor, similar to how we allow processes to open file descriptors to perform I/O operations.

For example, you can send a HTTP message to google.com server by putting the following in packet header:

- IP address: 216.58.221.78

- Port Number: 80 (for HTTP protocols)

A port number is specific to transport layer protocol, mainly TCP and UDP which we will learn later. The usage and interpretation of the port number depend on the transport layer protocol (such as TCP or UDP) being used. See practical examples in appendix below to find out more.

Socket API

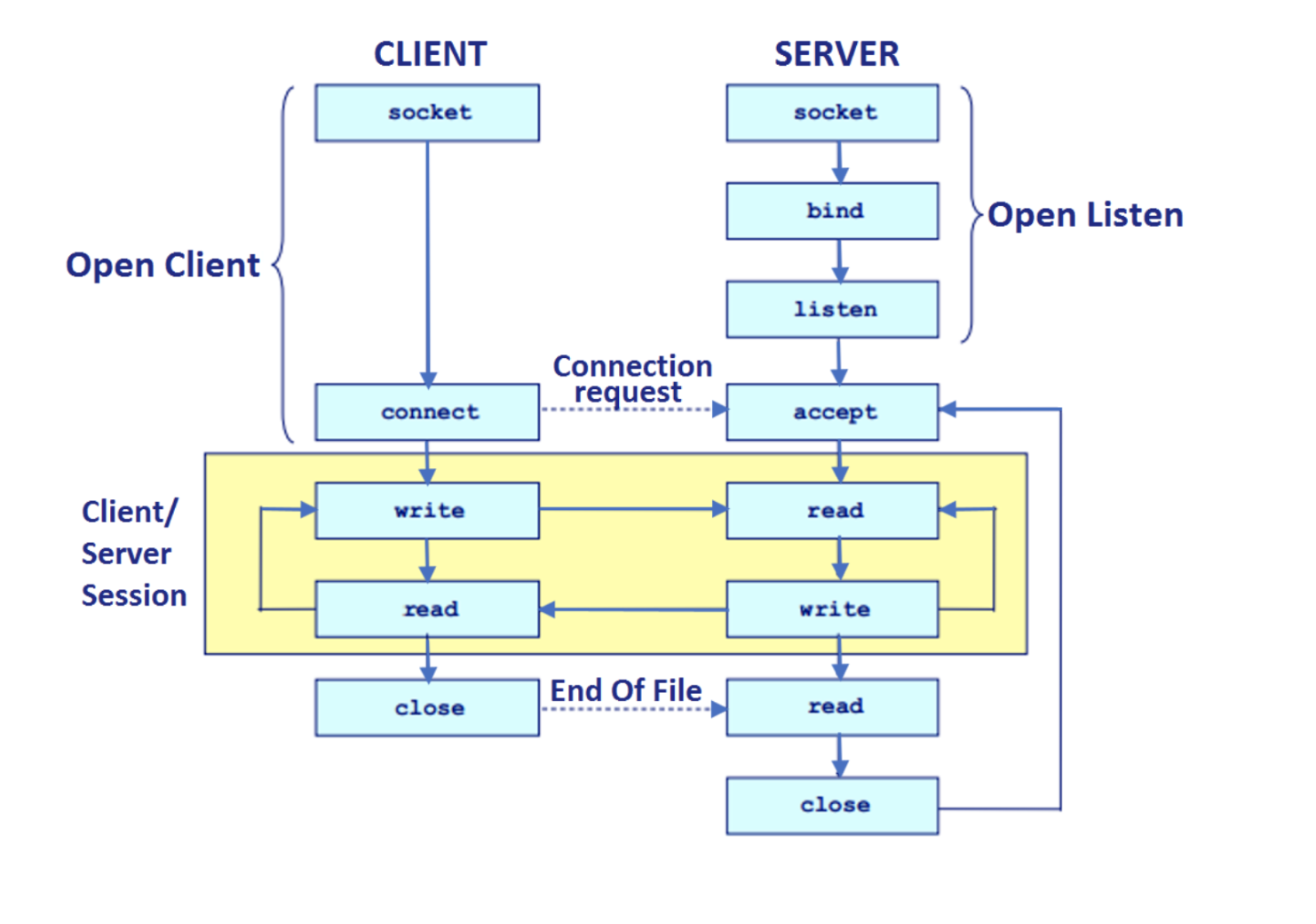

The Socket API provides a set of functions for network communication in programming. It allows developers to create and manage network connections between processes on different machines (using internet sockets) or on the same machine (using UNIX domain sockets). Below is an overview of the key concepts and functions provided by the Socket API:

For detailed implementation in C and Python, head to this appendix section.

Multiplexing and Demultiplexing

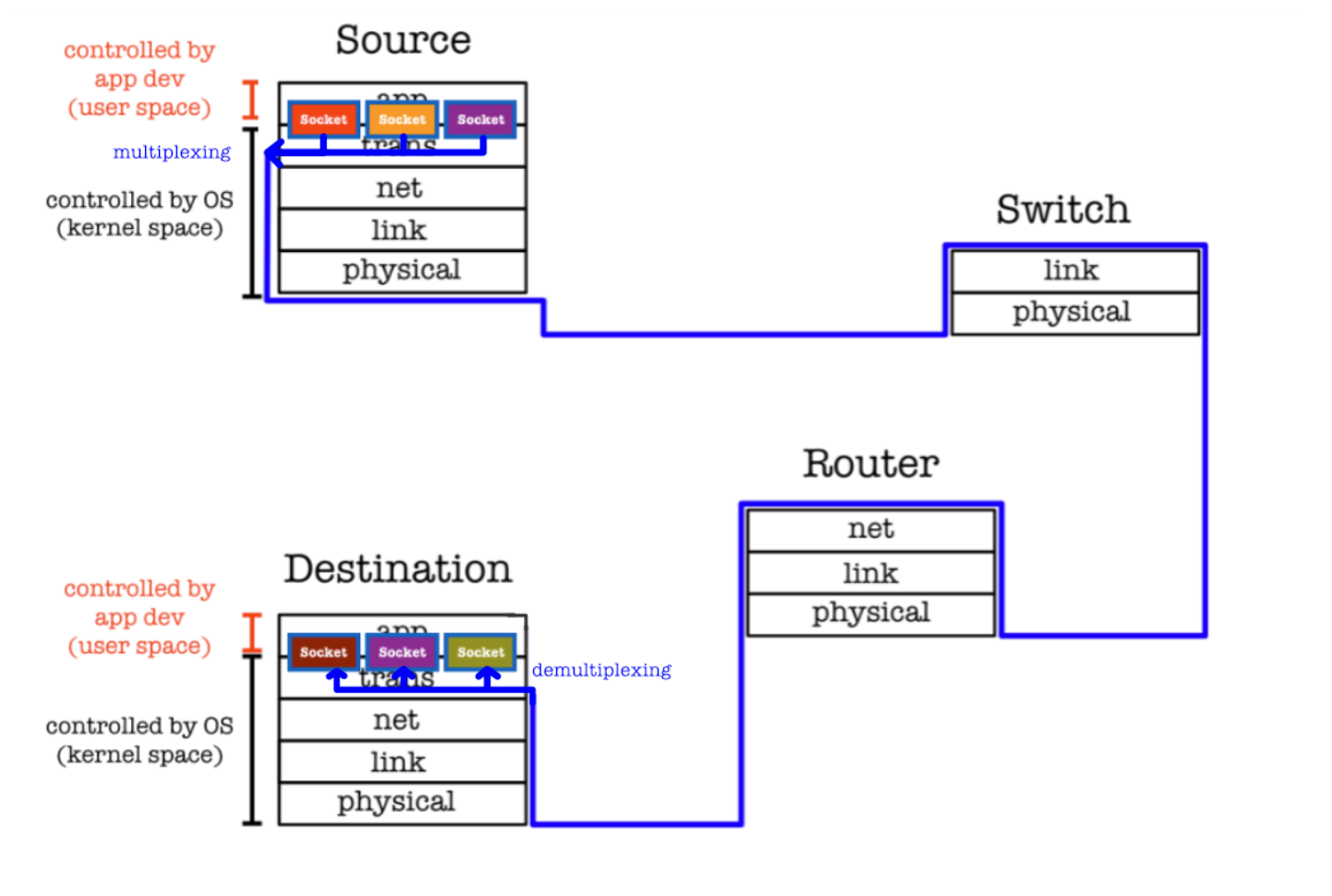

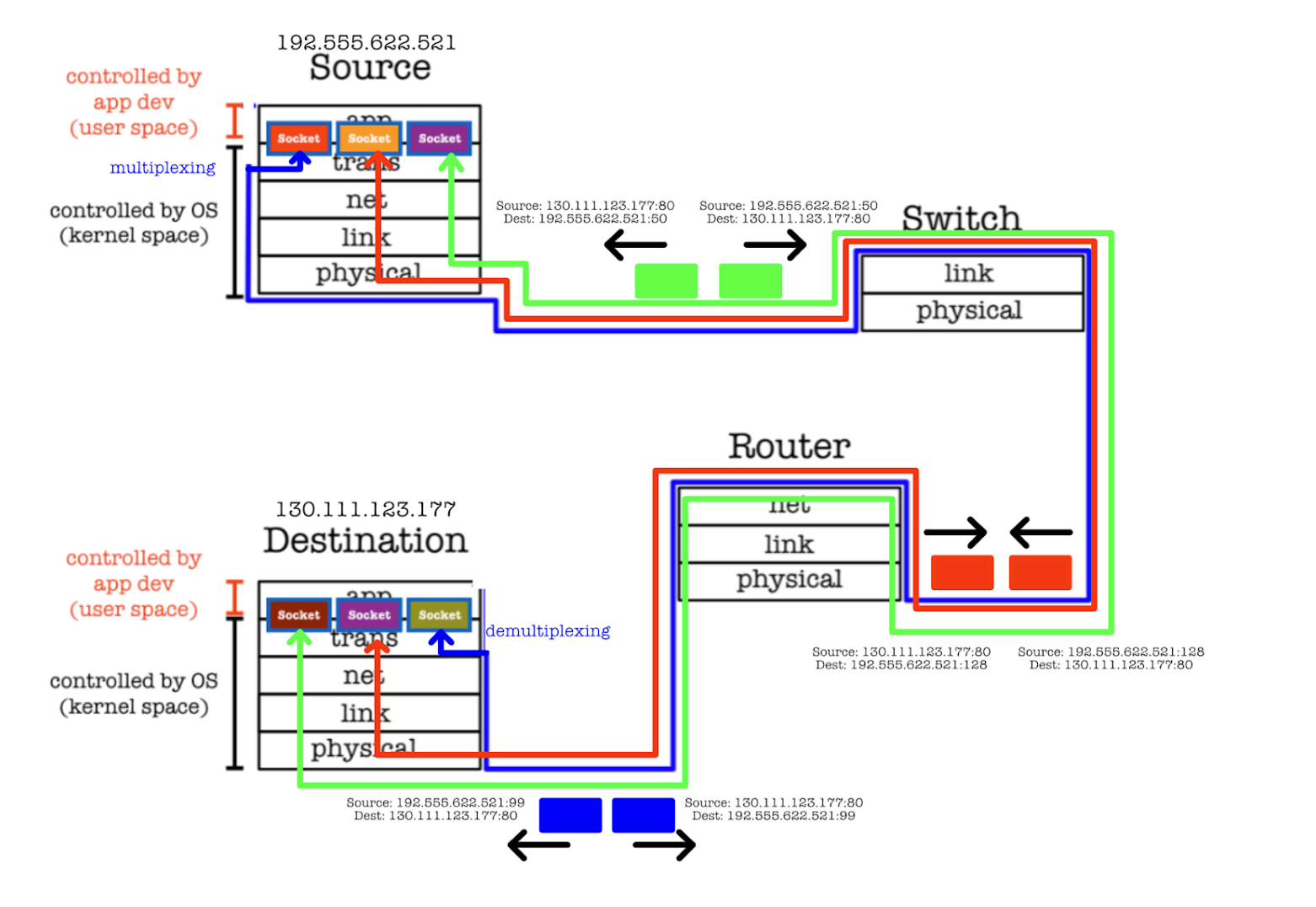

Since there are many applications that can be running on the hosts, the transport layer protocol multiplex at sender and demultiplex at receiver:

- Multiplexing: Multiplexing at the transport layer involves combining data from multiple application processes into a single stream of packets that can be sent over the network. The transport layer adds necessary headers (including source and destination port numbers) to each packet before passing them to the network layer.

- Demultiplexing: Demultiplexing is the process by which the transport layer receives packets from the network layer and directs them to the appropriate application process. This involves examining the headers of incoming packets to determine which application process should receive the data.

In the context of TCP and UDP, multiplexing and demultiplexing are handled by the kernel’s transport layer. The kernel uses port numbers in the transport layer headers to route incoming packets to the correct application process and to send outgoing data from multiple processes over the network efficiently.

When a TCP segment arrives, the kernel uses the destination port number, along with the source IP, source port, and destination IP, to identify the socket that is managing the connection. The segment is then passed to the appropriate socket buffer for the corresponding application process to read.

When a UDP datagram arrives, the kernel uses the destination port number + destination (this host’s) IP number to find the UDP socket bound to that number. It does not utilise source IP and source port to identify the UDP socket since UDP socket is connectionless.

Transport Layer Protocols

In the previous chapter, we learned that DNS is used to translate between hostname to its IP address. Then, we use a socket to direct the packet to the right application on the computer.

Now, we need communication protocols (transport layer protocols) between two applications over the internet so that the two may send packets in an orderly fashion.

The transport layer protocols that we will discuss are:

- TCP: Transmission Control Protocol

- UDP: User Datagram Protocol

Socket programming in the application layer relies on TCP and UDP services in the transport layer.

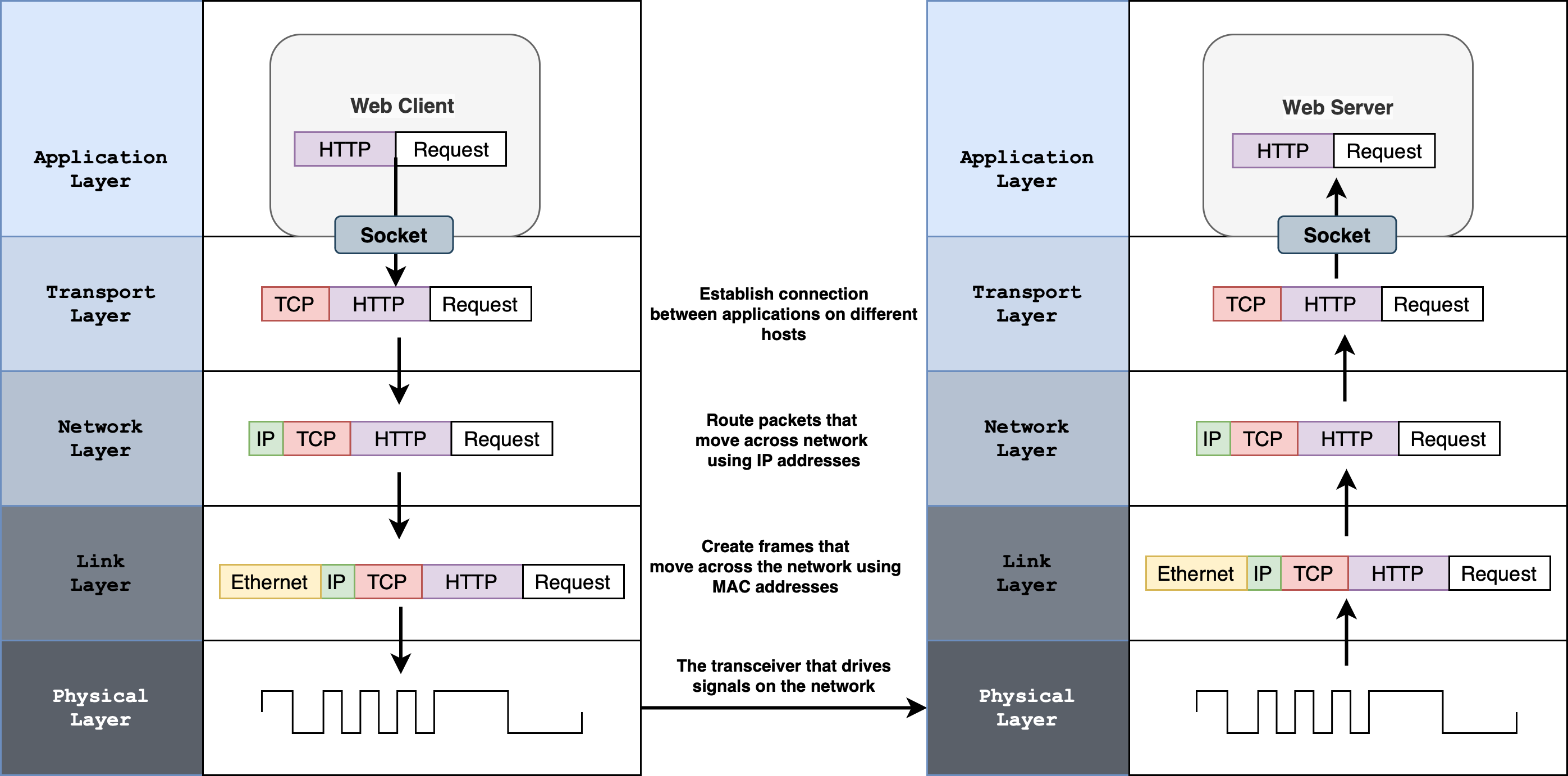

The diagram below might help you recap on the purpose of each network layer protocols:

TCP

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) provides reliable, in-order byte-stream transfer (“pipe”) between client and server in application viewpoint. It involves a three-way handshake process to establish a connection, ensuring that both parties are ready to communicate.

In terms of TCP implementation in UNIX-like systems, the series of instructions that handle TCP exists as part of the Kernel. For example, the Linux kernel is aware of the existence of network hardwares in the system and abstracts it into a set of link adapters. The TCP/UDP/IP stack is then aware of these adapters. They are further abstracted into higher-level concepts for users to use (via system-calls), such as the Socket API.

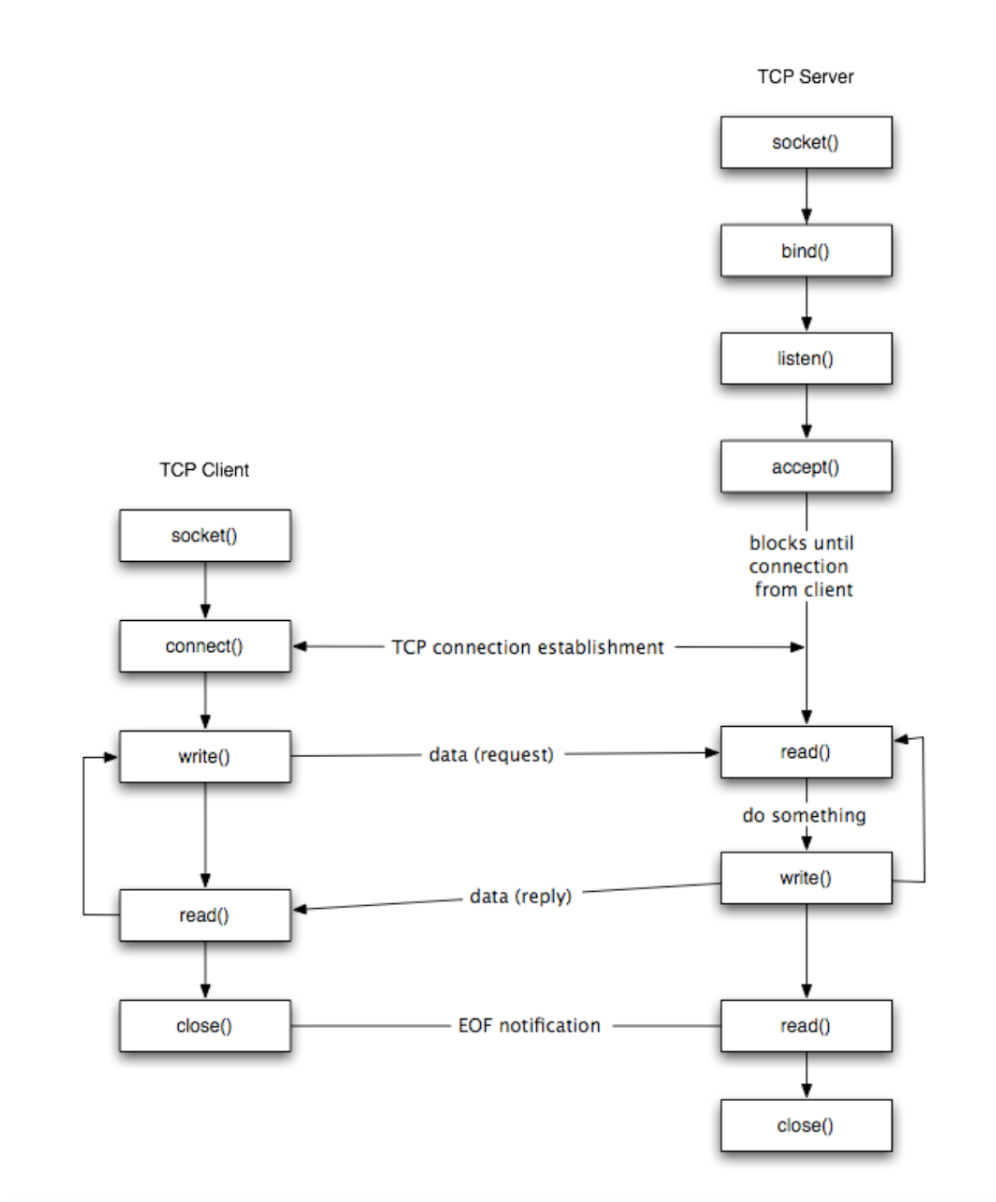

The general API for TCP is as shown below:

- TCP Socket is identified by 4 tuple: source IP address, source Port number, destination IP address, destination Port number

- TCP connection establishment:

- Step 1: Server process must at first be running, create socket that welcomes client’s contact

- Step 2: Client must contact server in Step 1 by creating TCP socket, specifying IP and port # of server host process

- Step 3: After Step 2 is done, server that’s contacted by client must create a new socket for server process to communicate with that particular client

- Step 4: After Step 3 is done, server process can continue accepting more clients, while communicating with multiple clients (with each different socket) who have established prior TCP connections using the same step (b) and (c)

Demultiplexing: receiver uses all four values to direct segment to the appropriate TCP socket. Multiplexing: server host support many simultaneous TCP connection, each socket is identified by its own unique 4-tuple.

The diagram below illustrates how demultiplexing and multiplexing is done:

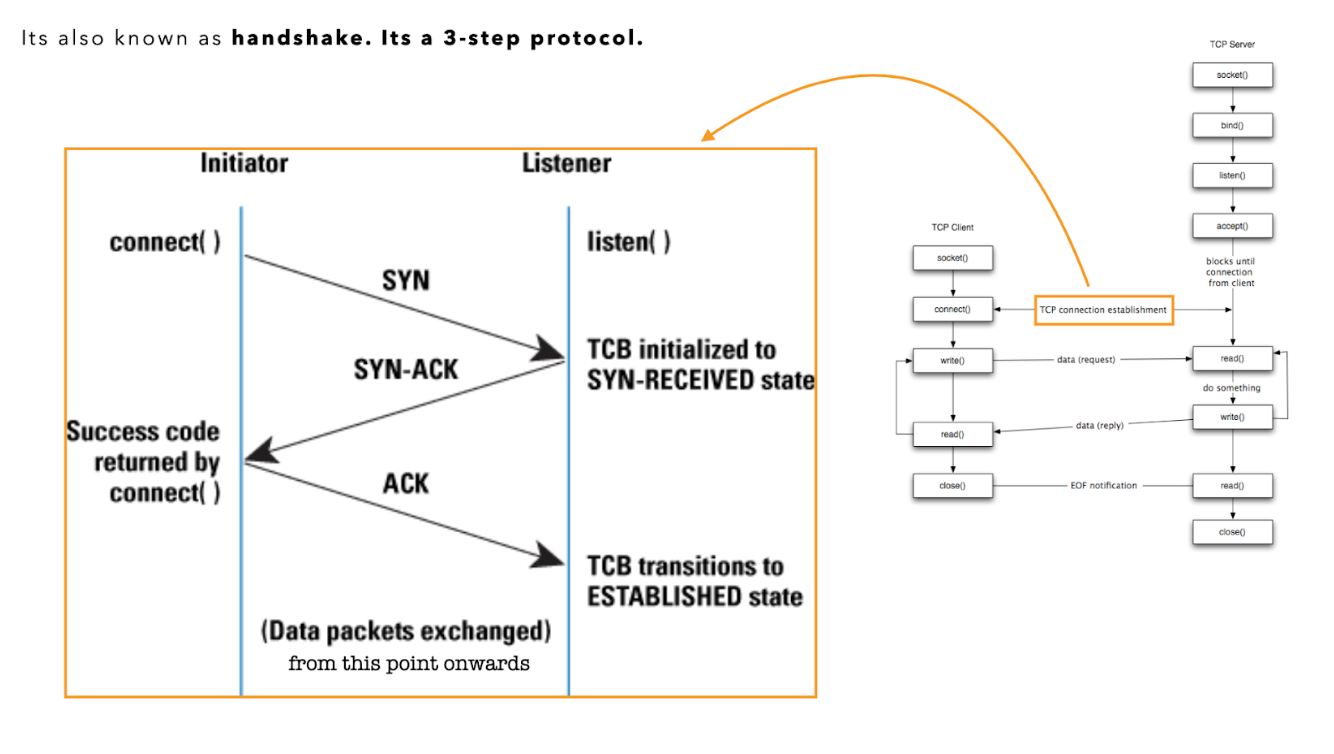

TCP Three-way Handshake

In particular, we are interested in the part denoted as TCP connection establishment,

The TCP three-way handshake is a crucial process used to establish a reliable connection between a client and a server in a TCP/IP network. This process ensures that both parties are ready to transmit and receive data.

Here’s a detailed explanation of the three-way handshake, including the SYN, SYN-ACK, and ACK packets

Steps in the TCP Three-Way Handshake

- SYN (Synchronize)

- SYN-ACK (Synchronize-Acknowledge)

- ACK (Acknowledge)

1. SYN (Synchronize)

- Initiator: Client

- Description: The client initiates the connection by sending a TCP segment with the SYN flag set. This packet includes an initial sequence number (ISN), which is a random value chosen by the client.

- Purpose: To inform the server that the client wants to establish a connection and to synchronize sequence numbers.

Client -> Server: SYN, Seq = X

2. SYN-ACK (Synchronize-Acknowledge)

- Initiator: Server

- Description: Upon receiving the SYN packet from the client, the server responds with a TCP segment that has both the SYN and ACK flags set. The server’s packet includes its own initial sequence number and acknowledges the client’s sequence number by incrementing it by one.

- Purpose: To acknowledge the client’s SYN packet and provide the server’s initial sequence number.

Server -> Client: SYN, ACK, Seq = Y, Ack = X + 1

3. ACK (Acknowledge)

- Initiator: Client

- Description: The client sends a final TCP segment with the ACK flag set. This packet acknowledges the server’s SYN-ACK packet by incrementing the server’s sequence number by one.

- Purpose: To acknowledge the server’s SYN-ACK packet and finalize the connection establishment.

Client -> Server: ACK, Seq = X + 1, Ack = Y + 1

Visualization of the Three-Way Handshake

Client Server

| SYN, Seq=X |

|----------------------->|

| SYN, ACK |

| Seq=Y, Ack=X+1 |

|<-----------------------|

| ACK, Seq=X+1 |

| Ack=Y+1 |

|----------------------->|

Detailed Breakdown

- SYN (Synchronize) Packet:

- The client sends a SYN packet to the server to initiate a connection.

- The packet contains the client’s initial sequence number (ISN = X).

- SYN-ACK (Synchronize-Acknowledge) Packet:

- The server responds with a SYN-ACK packet, acknowledging the receipt of the client’s SYN packet.

- The packet contains the server’s initial sequence number (ISN = Y) and acknowledges the client’s sequence number by setting the acknowledgment number to X+1.

- ACK (Acknowledge) Packet:

- The client sends an ACK packet to the server, acknowledging the receipt of the server’s SYN-ACK packet.

- The packet contains the client’s next sequence number (X+1) and acknowledges the server’s sequence number by setting the acknowledgment number to Y+1.

- Piggybacking: data can be sent along with an acknowledgment in the same packet.

- However, The final ACK in the TCP handshake acknowledges the server’s SYN-ACK and doesn’t need to carry any data.

- While the client may piggyback data with the ACK if ready, it’s not required; the ACK can simply be an empty acknowledgment in TCP.

In short, the SYN packet is used to initiate the connection. The SYN-ACK packet is used to acknowledge the SYN packet and provide the server’s sequence number. Finally, the ACK packet is used to acknowledge the SYN-ACK packet and finalize the connection establishment.

The three-way handshake is essential for establishing a reliable TCP connection, ensuring that both the client and server are ready to communicate and have synchronized sequence numbers for the data transfer that follows. You will be able to see the SYN, SYN-ACK, and ACK packets in the later labs using packet sniffing tools like Wireshark.

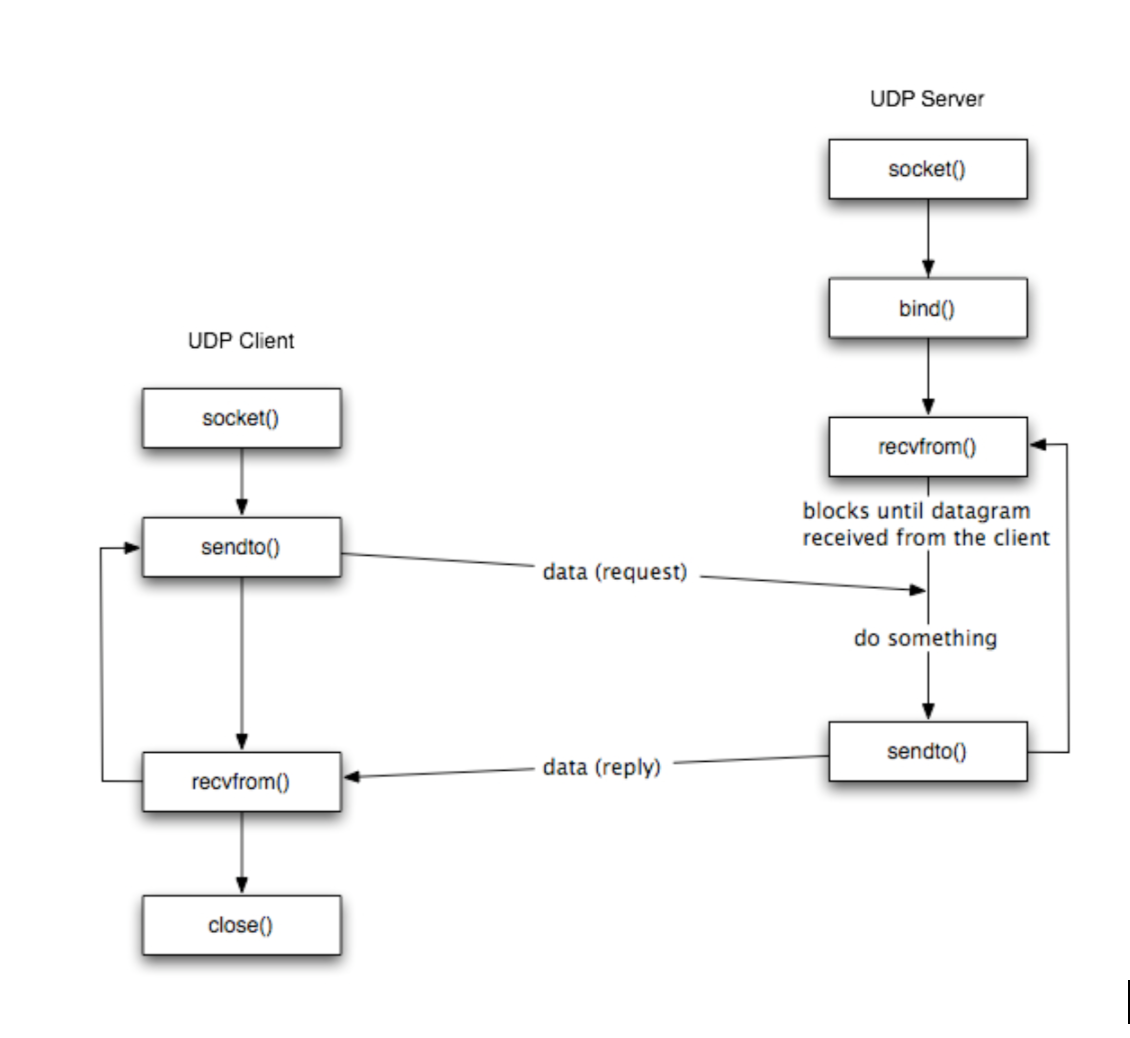

UDP

User Datagram Protocol (UDP) is also known as connectionless protocol. This protocol provides an unreliable-but-fast, may-be-out-of-order transfer of bytes between client and server.

Each datagram (packet) is sent independently, with no guarantee of order, delivery, or error correction. There is no handshake process; packets are simply sent to the destination without prior arrangement.

Like UDP, the series of instructions that handle UDP exists as part of the Kernel. The general API for UDP is as shown below:

- UDP socket is identified by 2-tuple only: IP and Port #

- In UDP, the client does not form a connection with the server like in TCP and instead just sends a datagram: attaches destination IP address and Port # to each packet

- Similarly, the server does not need to accept a connection and create a new socket like in TCP.

- Instead, it just waits for (any) datagram(s) to arrive from (any) clients: extracts sender’s IP address and port# from received packet

- Transmitted data using UDP may be lost or received out-of-order.

Details on how TCP and UDP implemented in the Kernel is not part of our syllabus.

Packet Header Format

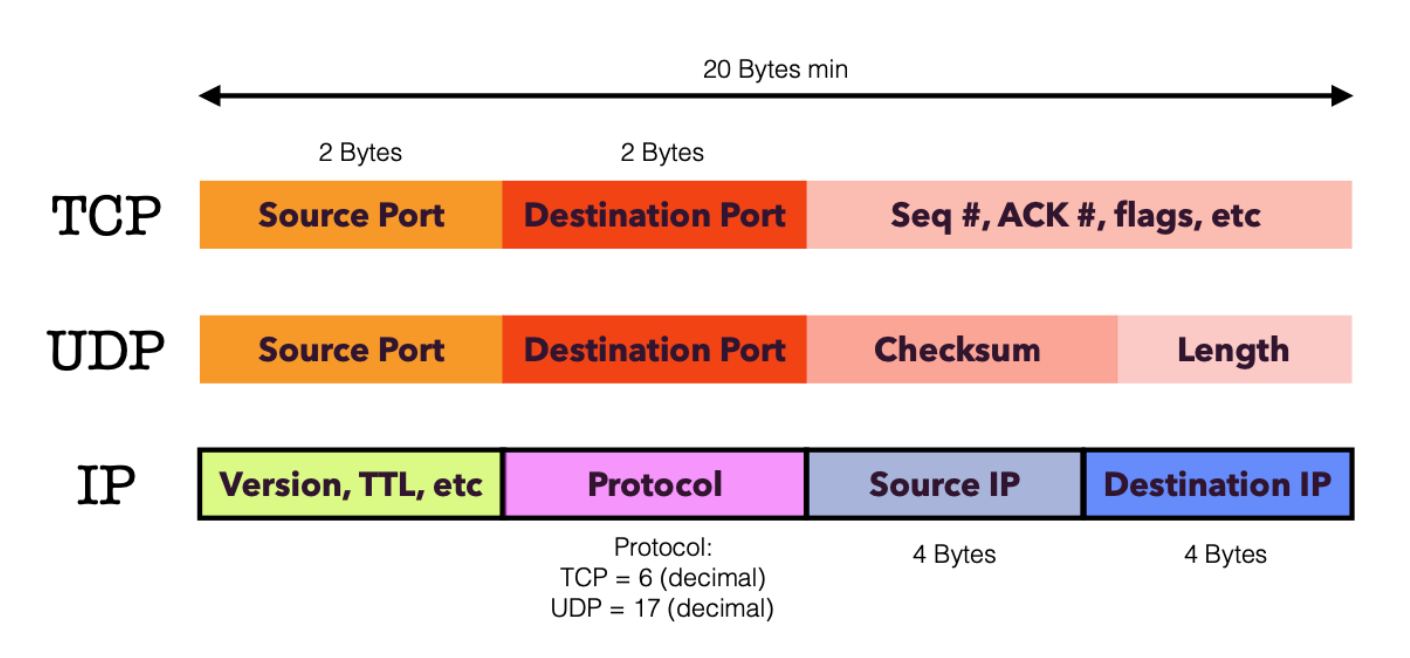

Information from the packet header will be used to demultiplex incoming packets to the correct socket, depending on whether the socket is UDP or TCP:

Note that this is a very simplified illustration. In practice, the packet header has all sorts of information, like source and destination port, source IP and destination IP, but not all may be used to identify sockets in the destination host, depending on whether the Socket in question relies on TCP or UDP.

Further information like IP addresses, MAC addresses, network topology information, and port number are typically accessible even at application layer even though application layer protocols dont directly manage these stuffs. These further information is made available for several reasons like diagnostics and logging, access control, security, session management, and many more.

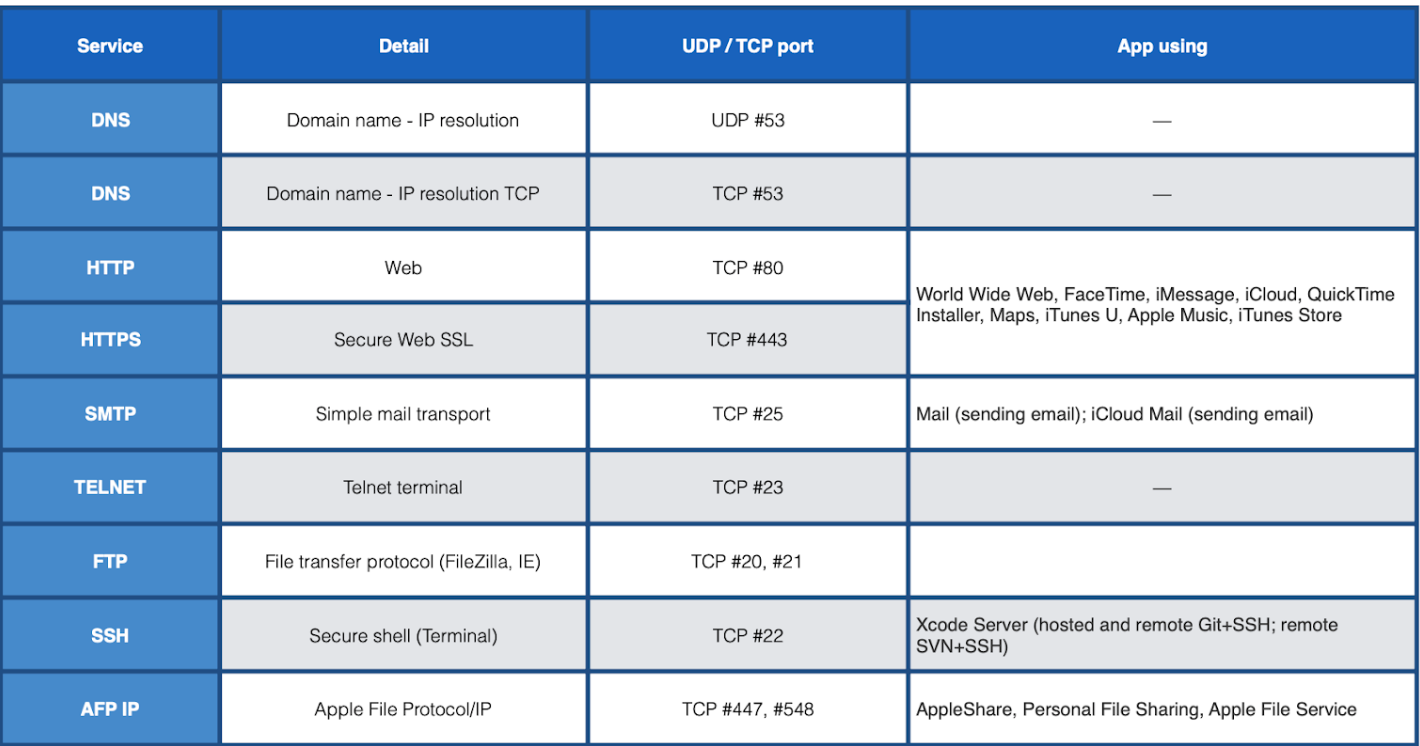

Common Port Numbers

The table below summarises common port numbers associated with specific application layer services. They’re typically reserved and you shouldn’t use these port numbers apart from supporting these services:

Sample TCP and UDP Socket Programming in C

You should run these sample code to enhance your understanding about socket programming (both TCP and UDP oriented) in C. We use C Socket API for this example. Simply ask ChatGPT to translate it to other socket API if you wish, e.g: Python socket API.

TCP

Server Code

The server is meant to be run first, before the client.

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <netinet/in.h> //contains constants and structures needed for internet domain addresses.

#include <string.h>

#define PORT 8080

int main(int argc, char const *argv[])

{

/**

* server_fd and new_socket are file descriptors, i.e. array subscripts into the file descriptor table. These two variables store the values returned by the socket system call and the accept system call.

* valread is the return value for the read() and write() calls; i.e. it contains the number of characters read or written.

**/

int server_fd, new_socket, valread;

/**

* A sockaddr_in is a structure containing an internet address. This structure is defined in <netinet/in.h>. Here is the definition:

struct sockaddr_in {

short sin_family;

u_short sin_port;

struct in_addr sin_addr;

char sin_zero[8];

};

*/

struct sockaddr_in address;

int addrlen = sizeof(address);

char buffer[1024] = {0}; //buffer used to read data from socket

char *hello = "Hello from server";

// Creating socket file descriptor, using socket system call

if ((server_fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0)) == 0)

{

perror("socket failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

In the server’s code, we use PORT 8080 (some unused port). We then prepare some local variables, and creating socket file descriptor server_fd.

The arguments that can be used for the socket is AF_INET (meaning connection through the internet) and SOCK_STREAM that represents TCP oriented connection. You can read the manual about SOCK_STREAM, but in essence SOCK_STREAM provides sequenced, reliable, two-way, connection-based byte streams. An out-of-band data transmission mechanism may be supported.

address.sin_family = AF_INET;

address.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

address.sin_port = htons( PORT );

// Forcefully attaching socket to the port 8080

if (bind(server_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&address,

sizeof(address))<0)

{

perror("bind failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

if (listen(server_fd, 3) < 0)

{

perror("listen");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

And then we accept() new connections. This blocks until a client connects to it. Note how new_socket is created upon connection with a client. The 3-way TCP handshake: SYN, SYN_ACK, and ACK handshake is handled by the transport layer during accept() (triggers system call).

During the execution of accept(), the transport layer handles this handshake process. The system call accept() essentially waits for this handshake to complete before returning the new socket descriptor. This ensures that the connection is fully established and ready for data transmission.

if ((new_socket = accept(server_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&address,

(socklen_t*)&addrlen))<0)

{

perror("accept");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

valread = read( new_socket , buffer, 1024);

printf("%s\n",buffer );

send(new_socket , hello , strlen(hello) , 0 );

printf("Hello message sent\n");

return 0;

}

Afterwards, server and client with can communicate using read() and send() API.

Keep-Alive

What if you want to create a new process to serve this client, so as to keep the server active to accept new connections? You can use fork() instead (or create threads, up to you) after accepting new_socket and ask the parent process to loop back up to accept new connection:

// multiple clients accepted

for (;;)

{

printf("Accepting new client\n");

if ((new_socket = accept(server_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&address, (socklen_t *)&addrlen)) < 0)

{

perror("accept");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

int pid;

if ((pid = fork()) == -1) // fork fails

{

close(new_socket);

continue;

}

else if (pid > 0) //parent process

{

close(new_socket);

continue;

}

else if (pid == 0) //child process

{

valread = read(new_socket, buffer, 1024);

printf("%s\n", buffer);

send(new_socket, hello, strlen(hello), 0);

printf("Hello message sent\n");

return 0;

}

}

Client Code

The client code for TCP is symmetrical:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#define PORT 8080

int main(int argc, char const *argv[])

{

int sock = 0, valread;

struct sockaddr_in serv_addr;

char *hello = "Hello from client";

char buffer[1024] = {0};

if ((sock = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0)) < 0)

{

printf("\n Socket creation error \n");

return -1;

}

serv_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

serv_addr.sin_port = htons(PORT);

// Convert IPv4 and IPv6 addresses from text to binary form

if(inet_pton(AF_INET, "127.0.0.1", &serv_addr.sin_addr)<=0) //localhost

{

printf("\nInvalid address/ Address not supported \n");

return -1;

}

if (connect(sock, (struct sockaddr *)&serv_addr, sizeof(serv_addr)) < 0)

{

printf("\nConnection Failed \n");

return -1;

}

send(sock , hello , strlen(hello) , 0 );

printf("Hello message sent\n");

valread = read( sock , buffer, 1024);

printf("%s\n",buffer );

return 0;

}

UDP

Server Code

The server is meant to be run first, before the client.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#define PORT 8080

#define MAXLINE 1024

// Driver code

int main() {

int sockfd;

char buffer[MAXLINE];

char *hello = "Hello from server";

struct sockaddr_in servaddr, cliaddr;

// Creating socket file descriptor

if ( (sockfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_DGRAM, 0)) < 0 ) {

perror("socket creation failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

Note how we create a socket with SOCK_DGRAM option instead. This option means we are expecting to rely on UDP.

SOCK_DGRAM supports datagrams (connectionless, unreliable messages of a fixed maximum length).

Similarly we need some setup with the socket, and then bind to it:

memset(&servaddr, 0, sizeof(servaddr));

memset(&cliaddr, 0, sizeof(cliaddr));

// Filling server information

servaddr.sin_family = AF_INET; // IPv4

servaddr.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

servaddr.sin_port = htons(PORT);

// Bind the socket with the server address

if ( bind(sockfd, (const struct sockaddr *)&servaddr,

sizeof(servaddr)) < 0 )

{

perror("bind failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// This section is unique to UDP

int len, n;

len = sizeof(cliaddr); //len is value/resuslt

n = recvfrom(sockfd, (char *)buffer, MAXLINE, MSG_WAITALL, ( struct sockaddr *) &cliaddr, &len);

buffer[n] = '\0';

printf("Client : %s\n", buffer);

sendto(sockfd, (const char *)hello, strlen(hello),

0, (const struct sockaddr *) &cliaddr,

len);

printf("Hello message sent.\n");

return 0;

}

Notice how there’s no need to accept and establish connection with a particular client. The server simply receive messages from any client that wants to send to this socket.

Client Code

The client code for UDP is also symmetrical:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#define PORT 8080

#define MAXLINE 1024

int main() {

int sockfd;

char buffer[MAXLINE];

char *hello = "Hello from client";

struct sockaddr_in servaddr;

// Creating socket file descriptor

if ( (sockfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_DGRAM, 0)) < 0 ) {

perror("socket creation failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

memset(&servaddr, 0, sizeof(servaddr));

// Filling server information

servaddr.sin_family = AF_INET;

servaddr.sin_port = htons(PORT);

servaddr.sin_addr.s_addr = inet_addr("127.0.0.1"); // localhost

int n, len;

sendto(sockfd, (const char *)hello, strlen(hello), 0, (const struct sockaddr *) &servaddr, sizeof(servaddr));

printf("Hello message sent.\n");

n = recvfrom(sockfd, (char *)buffer, MAXLINE, MSG_WAITALL, (struct sockaddr *) &servaddr, &len);

buffer[n] = '\0';

printf("Server : %s\n", buffer);

close(sockfd);

return 0;

}

The difference with the TCP client is that there’s no connect. You simply sendto and recvfrom the sockfd (identifying the server IP and port#) that you have defined.

Summary

The application layer, the topmost layer in the OSI model, provides network services directly to end-users or applications, serving as the interface between user applications and the network. While relying on the transport layer for data transmission, it ensures seamless network interactions.

Sockets, which combine an IP address and port number to identify a specific process on a machine, are crucial for network communication. They act as the programming interface between the application and transport layers, enabling applications to use transport layer services.

Two main types of sockets exist:

- Stream Sockets (TCP): For connection-oriented, reliable, ordered, and error-checked data delivery.

- Datagram Sockets (UDP): For connectionless, faster, but less reliable data transfer without order or error-checking.

Sockets support interprocess communication, with each having a unique identifier (IP address + Port number). Applications bind and listen to these sockets to communicate. In UNIX systems, sockets are special file descriptors similar to file I/O operations.

The Socket API provides functions for network communication, allowing developers to create and manage connections between processes on different or the same machines.

Transport layer protocols handle multiplexing and demultiplexing of data:

- Multiplexing: Handles data from multiple sockets, adding transport headers.

- Demultiplexing: Uses headers to deliver segments to the correct socket.

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) ensures reliable, in-order byte-stream transfer, while UDP (User Datagram Protocol) provides faster, connectionless communication with less reliability.

Appendix

Transport Layer Services

Recall from our first chapter that transport layer is responsible for providing various services that ensure the effective transmission of data between applications. These services include:

- Segmentation and Reassembly: Breaking down large messages into smaller segments for transmission and reassembling them at the destination.

- Error Detection and Correction: Ensuring that data is delivered accurately by detecting and correcting errors that may occur during transmission.

- Flow Control: Managing the rate at which data is transmitted to prevent overwhelming the receiver.

- Congestion Control: Preventing network congestion by controlling the amount of data entering the network.

Transport Layer Protocols

There are two major transport layer protocols:

- Transmission Control Protocol (TCP):

- Connection-Oriented: Establishes a connection before data transfer begins.

- Reliable: Ensures that data is delivered accurately and in the correct order.

- Flow and Congestion Control: Implements mechanisms to manage data flow and avoid network congestion.

- Use Case: Applications requiring reliable communication, such as web browsers (HTTP/HTTPS), email clients (SMTP/IMAP/POP3), and file transfer applications (FTP).

- User Datagram Protocol (UDP):

- Connectionless: No need to establish a connection before data transfer.

- Unreliable: Does not guarantee data delivery, order, or error-checking.

- Low Overhead: Faster data transmission with minimal overhead.

- Use Case: Applications where speed is crucial and some data loss is acceptable, such as video streaming, online gaming, and VoIP (Voice over IP).

Interaction between Application Layer and Transport Layer:

When an application sends data, it passes the data to the transport layer through a socket. The transport layer then encapsulates the data into segments (for TCP) or datagrams (for UDP), adding necessary headers for error detection, flow control, and other functions. This encapsulated data is then passed down to the lower layers for transmission across the network.

Upon receiving data, the transport layer at the destination decapsulates the segments or datagrams, checks for errors, reassembles the data (if using TCP), and passes it up to the application layer through the socket. The application can then process the received data.

The application layer relies on the transport layer to provide reliable and efficient data transfer services. Sockets act as the interface between these two layers, enabling applications to communicate over the network using transport layer protocols like TCP and UDP. This layered approach ensures that applications can transmit data accurately, efficiently, and securely across the network.

File Sockets

File sockets, also known as UNIX domain sockets or IPC (Inter-Process Communication) sockets, are used for communication between processes running on the same host. They are similar to network sockets but do not use the network stack. Instead, they use the file system for communication, making them faster and more efficient for local inter-process communication.

Key Characteristics of UNIX Domain Sockets:

- Local Communication:

- UNIX domain sockets are designed for communication between processes on the same host.

- They are not routable, meaning they cannot be used to communicate between processes on different machines.

- File System Integration:

- UNIX domain sockets are represented as special files in the file system.

- They are created with a specific path in the file system (e.g.,

/tmp/my_socket).

- Socket Types:

- Stream Sockets (SOCK_STREAM): Provide reliable, connection-oriented communication similar to TCP.

- Datagram Sockets (SOCK_DGRAM): Provide connectionless communication similar to UDP.

- Sequential Packet Sockets (SOCK_SEQPACKET): Provide a connection-oriented service that preserves message boundaries.

- Performance:

- Because they bypass the network stack, UNIX domain sockets offer lower latency and higher throughput compared to internet sockets for local communication.

How UNIX Domain Sockets Work:

- Creating a Socket:

- A server process creates a socket using the

socketsystem call and binds it to a file path using thebindsystem call. - The server listens for incoming connections using the

listensystem call.

- A server process creates a socket using the

- Connecting to a Socket:

- A client process creates a socket and connects to the server’s socket using the

connectsystem call with the file path of the server’s socket.

- A client process creates a socket and connects to the server’s socket using the

- Communication:

- Once connected, the server and client can communicate using

sendandrecvsystem calls for stream sockets, orsendtoandrecvfromfor datagram sockets.

- Once connected, the server and client can communicate using

Example in C:

Here is a simple example demonstrating the creation and use of UNIX domain sockets in C:

Server Code:

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/un.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define SOCKET_PATH "/tmp/my_socket"

int main() {

int server_fd, client_fd;

struct sockaddr_un addr;

char buffer[100];

server_fd = socket(AF_UNIX, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

if (server_fd < 0) {

perror("socket");

return 1;

}

memset(&addr, 0, sizeof(struct sockaddr_un));

addr.sun_family = AF_UNIX;

strncpy(addr.sun_path, SOCKET_PATH, sizeof(addr.sun_path) - 1);

unlink(SOCKET_PATH);

if (bind(server_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&addr, sizeof(struct sockaddr_un)) < 0) {

perror("bind");

return 1;

}

if (listen(server_fd, 5) < 0) {

perror("listen");

return 1;

}

client_fd = accept(server_fd, NULL, NULL);

if (client_fd < 0) {

perror("accept");

return 1;

}

read(client_fd, buffer, sizeof(buffer));

printf("Received: %s\n", buffer);

close(client_fd);

close(server_fd);

unlink(SOCKET_PATH);

return 0;

}

Client Code:

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/un.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define SOCKET_PATH "/tmp/my_socket"

int main() {

int client_fd;

struct sockaddr_un addr;

const char *message = "Hello, server!";

client_fd = socket(AF_UNIX, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

if (client_fd < 0) {

perror("socket");

return 1;

}

memset(&addr, 0, sizeof(struct sockaddr_un));

addr.sun_family = AF_UNIX;

strncpy(addr.sun_path, SOCKET_PATH, sizeof(addr.sun_path) - 1);

if (connect(client_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&addr, sizeof(struct sockaddr_un)) < 0) {

perror("connect");

return 1;

}

write(client_fd, message, strlen(message));

close(client_fd);

return 0;

}

Conclusion

- UNIX domain sockets provide efficient inter-process communication on the same host.

- They are represented as special files in the file system and use file paths for addressing.

- They can be used as stream sockets (similar to TCP) or datagram sockets (similar to UDP).

- Due to bypassing the network stack, they offer improved performance for local communications compared to internet sockets.

Practical Examples of Port Usage

1. Web Browsing (HTTP/HTTPS)

- Protocol: TCP

- Port Number: 80 (HTTP), 443 (HTTPS)

- Explanation:

- When you type a URL in your web browser and hit enter, the browser initiates a TCP connection to the web server’s IP address on port 80 (for HTTP) or port 443 (for HTTPS).

- This connection ensures reliable data transfer, ensuring the web pages load correctly and securely.

2. Email (SMTP, IMAP, POP3)

- Protocol: TCP

- Port Numbers:

- SMTP: 25, 587 (sending email)

- IMAP: 143 (unencrypted), 993 (encrypted)

- POP3: 110 (unencrypted), 995 (encrypted)

- Explanation:

- SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol) is used for sending emails. Email clients and servers use TCP port 25 or 587 to send emails reliably.

- IMAP (Internet Message Access Protocol) and POP3 (Post Office Protocol) are used to retrieve emails. They use ports 143 and 110 respectively for unencrypted access, and ports 993 and 995 for encrypted access to ensure emails are downloaded and managed reliably.

3. DNS (Domain Name System)

- Protocol: UDP and TCP

- Port Number: 53

- Explanation:

- DNS queries are typically made over UDP port 53 because they are small and the connectionless nature of UDP allows for quick query resolution.

- For larger responses, such as DNS zone transfers, TCP port 53 is used to ensure the complete transfer of data.

4. File Transfer (FTP)

- Protocol: TCP

- Port Numbers: 21 (control), 20 (data)

- Explanation:

- FTP (File Transfer Protocol) uses TCP port 21 to establish a control connection between the client and server.

- The actual file data is transferred over a separate connection using TCP port 20.

5. Streaming Media (RTSP, RTP)

- Protocol: UDP and TCP

- Port Numbers:

- RTSP (Real-Time Streaming Protocol): 554 (TCP)

- RTP (Real-Time Transport Protocol): Dynamic ports (UDP)

- Explanation:

- RTSP uses TCP port 554 for establishing and controlling media sessions.

- RTP streams the actual media content over dynamic UDP ports for low latency and fast delivery.

6. Secure Shell (SSH)

- Protocol: TCP

- Port Number: 22

- Explanation:

- SSH (Secure Shell) uses TCP port 22 to provide secure, encrypted communication for remote login and other secure network services.

7. Remote Desktop (RDP)

- Protocol: TCP

- Port Number: 3389

- Explanation:

- RDP (Remote Desktop Protocol) uses TCP port 3389 to allow users to connect to and control another computer remotely with a graphical interface.

8. Voice over IP (VoIP)

- Protocol: UDP and TCP

- Port Numbers:

- SIP (Session Initiation Protocol): 5060 (unencrypted), 5061 (encrypted) (TCP/UDP)

- RTP (Real-Time Transport Protocol): Dynamic ports (UDP)

- Explanation:

- SIP uses TCP or UDP ports 5060 and 5061 to establish and manage VoIP calls.

- RTP uses dynamic UDP ports to transmit the actual voice data with minimal latency.

9. Game Servers

- Protocol: UDP and TCP

- Port Numbers: Varies by game

- Explanation:

- Online multiplayer games often use specific ports for game data transmission. For example, Minecraft uses TCP/UDP port 25565.

- These games often use UDP for fast-paced data transmission where occasional packet loss is acceptable.

10. Network Time Protocol (NTP)

- Protocol: UDP

- Port Number: 123

- Explanation:

- NTP uses UDP port 123 to synchronize the clocks of computers over a network.

These examples show how different applications and services utilize specific port numbers and transport layer protocols (TCP or UDP) based on their requirements for reliability, speed, and connection management. Understanding the appropriate use of ports and protocols helps in configuring, troubleshooting, and securing network communications.

Socket API Example

The Socket API provides a set of functions for network communication in programming. It allows developers to create and manage network connections between processes on different machines (using internet sockets) or on the same machine (using UNIX domain sockets). Below is an overview of the key concepts and functions provided by the Socket API.

Key Concepts

- Socket: An endpoint for communication, defined by an IP address and port number.

- Types of Sockets:

- Stream Sockets (SOCK_STREAM): Use TCP for reliable, connection-oriented communication.

- Datagram Sockets (SOCK_DGRAM): Use UDP for connectionless, unreliable communication.

- UNIX Domain Sockets: Used for inter-process communication on the same machine.

Socket API Functions

C Example

1. Creating a Socket

C Example:

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

int socket(int domain, int type, int protocol);

domain: Specifies the protocol family (e.g.,AF_INETfor IPv4,AF_INET6for IPv6,AF_UNIXfor UNIX domain sockets).type: Specifies the communication semantics (e.g.,SOCK_STREAMfor TCP,SOCK_DGRAMfor UDP).protocol: Specifies a particular protocol to be used with the socket (usually set to 0 to select the default protocol).

2. Binding a Socket

C Example:

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

int bind(int sockfd, const struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t addrlen);

sockfd: The file descriptor of the socket.addr: A pointer to asockaddrstructure containing the address to bind to.addrlen: The size of the address structure.

3. Listening for Connections

C Example:

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

int listen(int sockfd, int backlog);

sockfd: The file descriptor of the socket.backlog: The maximum number of pending connections that can be queued.

4. Accepting a Connection

C Example:

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

int accept(int sockfd, struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t *addrlen);

sockfd: The file descriptor of the listening socket.addr: A pointer to asockaddrstructure to receive the address of the connecting entity.addrlen: A pointer to a variable that specifies the size of the address structure.

5. Connecting to a Server

C Example:

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

int connect(int sockfd, const struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t addrlen);

sockfd: The file descriptor of the socket.addr: A pointer to asockaddrstructure containing the address of the server.addrlen: The size of the address structure.

6. Sending and Receiving Data

C Example:

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

ssize_t send(int sockfd, const void *buf, size_t len, int flags);

ssize_t recv(int sockfd, void *buf, size_t len, int flags);

sockfd: The file descriptor of the socket.buf: A pointer to the buffer containing the data to be sent or to receive the data.len: The length of the buffer.flags: Flags to modify the behavior of the function (usually set to 0).

7. Closing a Socket

C Example:

#include <unistd.h>

int close(int fd);

fd: The file descriptor of the socket.

Python Example

Here’s how you can use the Socket API in Python to create a simple client-server application:

Server Code:

import socket

# Create a socket object

server_socket = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

# Get local machine name

host = socket.gethostname()

port = 12345

# Bind the socket to a public host and a port

server_socket.bind((host, port))

# Become a server socket

server_socket.listen(5)

print("Server listening...")

while True:

# Establish a connection

client_socket, addr = server_socket.accept()

print(f"Got a connection from {addr}")

msg = "Thank you for connecting"

client_socket.send(msg.encode('ascii'))

client_socket.close()

Client Code:

import socket

# Create a socket object

client_socket = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

# Get local machine name

host = socket.gethostname()

port = 12345

# Connection to hostname on the port

client_socket.connect((host, port))

# Receive no more than 1024 bytes

msg = client_socket.recv(1024)

print(msg.decode('ascii'))

client_socket.close()

The Socket API provides a comprehensive set of functions for network communication, allowing developers to create, manage, and close socket connections. Understanding these functions is crucial for implementing networked applications, whether they involve internet sockets for communication over a network or UNIX domain sockets for inter-process communication on the same host.

About Socket Binding

Basics

Socket binding is the process of associating a socket with a specific IP address and port number on a host. This is an essential step for server applications, as it prepares the socket to listen for incoming connections on a particular network interface and port. Binding allows the operating system to forward incoming network packets to the correct socket based on the specified IP address and port number.

Why Binding is Important

- Listening for Connections: Binding is necessary for a server to listen for incoming connections or datagrams on a specific port.

- Address Specification: It allows the server to specify which network interface (IP address) and port it should use. This is important for multi-homed hosts (hosts with multiple network interfaces).

How Binding Works

When you bind a socket, you tell the operating system that you want to use a specific port and optionally a specific IP address for communication. This involves providing a sockaddr structure that contains the IP address and port number.

Example: Binding a Socket in C

Here’s a simple example of how to bind a socket in C using the socket API:

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define PORT 8080

int main() {

int server_fd;

struct sockaddr_in address;

int opt = 1;

int addrlen = sizeof(address);

// Creating socket file descriptor

if ((server_fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0)) == 0) {

perror("socket failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Forcefully attaching socket to the port 8080

if (setsockopt(server_fd, SOL_SOCKET, SO_REUSEADDR | SO_REUSEPORT, &opt, sizeof(opt))) {

perror("setsockopt");

close(server_fd);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

address.sin_family = AF_INET;

address.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY; // Bind to any available interface

address.sin_port = htons(PORT);

// Binding the socket to the specified IP address and port

if (bind(server_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&address, sizeof(address)) < 0) {

perror("bind failed");

close(server_fd);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

printf("Socket successfully bound to port %d\n", PORT);

// Listening for incoming connections

if (listen(server_fd, 3) < 0) {

perror("listen");

close(server_fd);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

printf("Listening for incoming connections...\n");

return 0;

}

Explanation

- Socket Creation:

socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0)creates a new socket using the IPv4 address family and TCP (SOCK_STREAM). - Set Socket Options:

setsockopt()allows the socket to be reused quickly after the application is closed and restarted. - Address Setup:

address.sin_family = AF_INETsets the address family to IPv4.address.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANYallows the socket to bind to all available network interfaces.address.sin_port = htons(PORT)sets the port number, converting it to network byte order.

- Binding:

bind(server_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&address, sizeof(address))binds the socket to the specified IP address and port. - Listening:

listen(server_fd, 3)puts the socket into listening mode, ready to accept incoming connections.

Example: Binding a Socket in Python

Here’s how you can bind a socket in Python using the socket module:

import socket

# Create a socket object

server_socket = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

# Get local machine name

host = socket.gethostname()

port = 8080

# Bind the socket to the port

server_socket.bind((host, port))

print(f"Socket successfully bound to port {port}")

# Put the socket into listening mode

server_socket.listen(5)

print("Listening for incoming connections...")

while True:

# Establish a connection

client_socket, addr = server_socket.accept()

print(f"Got a connection from {addr}")

client_socket.send(b"Thank you for connecting")

client_socket.close()

Conclusion

- Binding: The process of associating a socket with a specific IP address and port number.

- Purpose: Necessary for a server to listen for incoming connections on a specific port.

- Steps:

- Create a socket.

- Set socket options (optional).

- Define the address structure (IP address and port).

- Bind the socket to the address.

- Listen for incoming connections.

Understanding socket binding is crucial for developing server applications that need to handle network communication. It ensures that the server can accept and process incoming requests on the designated network interface and port.

Multiple Process Binding

Can many applications listen (or bind) to the same TCP socket? It depends. You may do your own Googling as this is not a simple question. Many updates happen all the time to improve our Operating System.

Lets begin with traditional Kernel:

- Remember in a definition of a socket: its port is (one part of) an address. The full address includes the IP address.

- In order to initiate communication, one end needs to be known to another.

- In protocols that have “known” ports, the prearranged end is called the passive server / socket listener “listening” at the server end. For example, the HTTP web server listens at port 80.

In a traditional sense, Operating systems only allow a single process to own a passive port. The first process request it via the “bind” system call in most operating systems

However we can have multiple programs able to listen to the same port, but a slight variation than “normal TCP”:

- For protocols like TCP, it is not so simple, in that once connected, a virtual circuit is formed between the client and the server apps. That is identified not by just an IP address and port, but by a four tuple that we know: - 192.168.0.1:23875 - 192.168.0.2:80, for example. Each such virtual circuit is unique.

- To have a program broadcast traffic from a single port to multiple other programs using such a protocol, you’ll need to make the broadcast end passive mode (ie, listen to a known port), and then send the traffic (commands, or whatever) to each program that connects in individually - but this will mean they all get the same data and only the program in question will respond and be connected to the requesting client.

The other programs won’t be “listening” in the TCP manner - but they can listen to the commands sent by the server. Many existing protocols work like this - like Message Queues (AMQP, RabbitMQ, and so on) or Publish/Subscribe (XMPP’s XEP-0060, for example).

With UDP, it is the same concept. While only one program per computer can listen to the port in its traditional sense, a service app could broadcast to all subscribers at once (in a single network packet).

- For example in UDP we can do multicast. Multicast uses “special” IP addresses which can be listened to by multiple computers at once.

- In situations where multiple processes bind to the same UDP multicast socket, the incoming traffic that eventually reaches the actively listening service program on the designated port can serve as a ‘proxy’ mechanism. These programs can then further relay the data to other internal programs that require the information, effectively distributing the data among different processes.

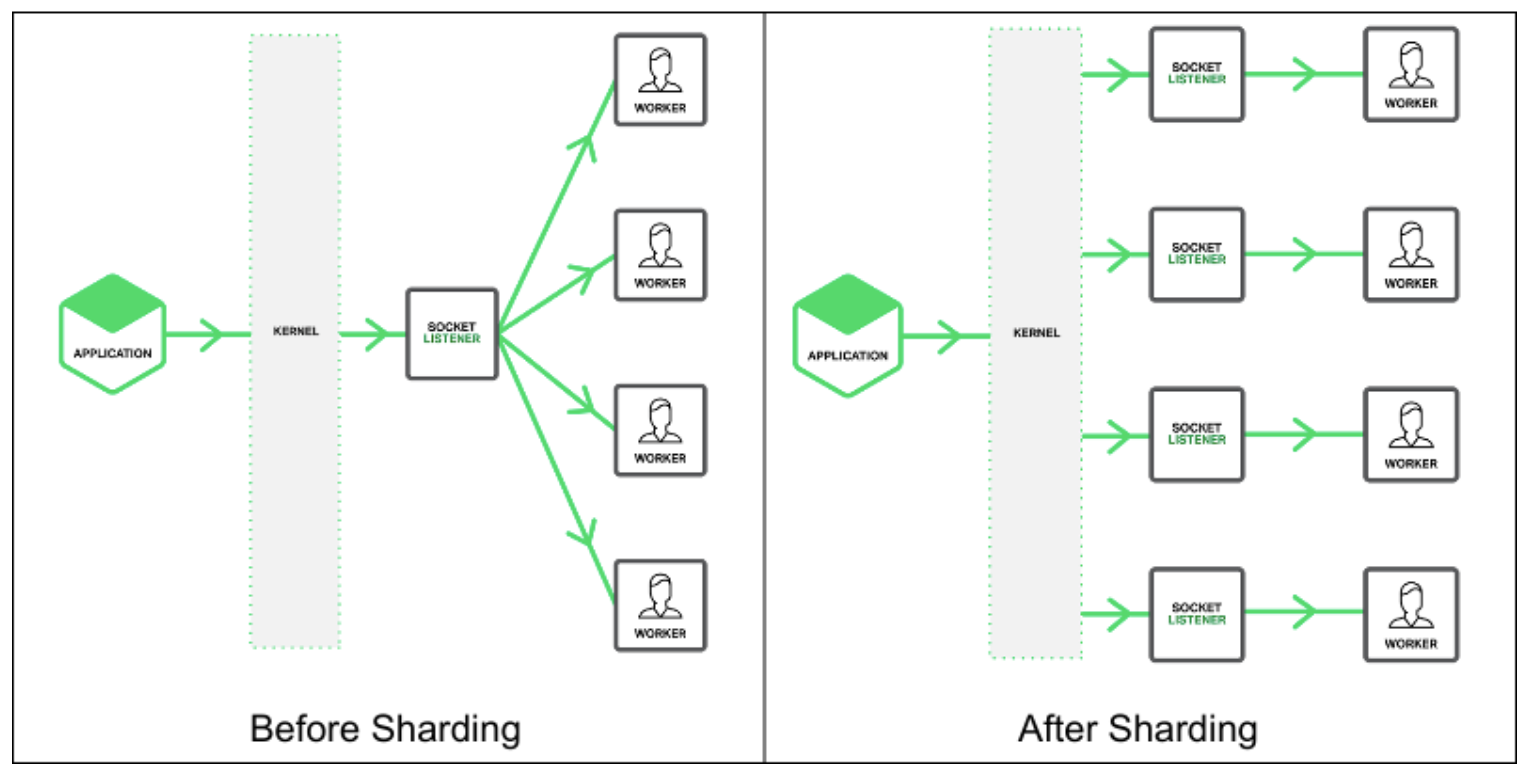

Modern Kernel: Port Sharding

In Linux Kernel 3.9, there is a new feature called Port Sharding, where you can create a socket for multiple threads / processes to bind and listen to.

The basic concept of SO_REUSEPORT is simple enough. Multiple servers (processes or threads) can bind to the same port if they each set the option as follows and listen to the socket at the same time:

int sfd = socket(domain, socktype, 0);

int optval = 1;

setsockopt(sfd, SOL_SOCKET, SO_REUSEPORT, &optval, sizeof(optval));

bind(sfd, (struct sockaddr *) &addr, addrlen);

Port Sharding is good for performance. Before there’s Port sharding, the model is that there should be a proxy, single passive server (socket listener) that accepts connections and helps the client app connect to the relevant process/thread. With port sharding, the fundamental changes:

Image taken from here.

50.005 CSE

50.005 CSE