- How the Web Works

- HTTP Connection Types

- HTTP Message Format

- Secure HTTP (HTTPs)

- Cookies

- Web Cache

- Modern HTTP

- Summary

- Appendix

50.005 Computer System Engineering

Information Systems Technology and Design

Singapore University of Technology and Design

Natalie Agus (Summer 2025)

Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP)

Detailed Learning Objectives

- Explain the basics of HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol)

- Define HTTP and its role in web data exchange

- Explain the difference between HTTP and HTTPS

- Identify the components of an HTTP request and response

- Describe the client/server model in HTTP

- Define the roles of the client and server in HTTP communication

- Illustrate the process of a client initiating a connection and requesting web resources

- Differentiate between non-persistent and persistent HTTP connections

- Explain the characteristics and limitations of non-persistent HTTP (HTTP 1.0)

- Describe the benefits and functioning of persistent HTTP (HTTP 1.1)

- Interpret the concept of URLs and their structure

- Define what a URL is and its components

- Explain how URLs are used to access web resources

- Explain the significance of cookies in maintaining state

- Define cookies and their purpose in HTTP communication

- Explain the structure and components of cookies

- Discuss the potential security and privacy risks associated with cookies

- Discuss web caching and its benefits

- Define web caching and its purpose

- Describe the role of conditional GET requests in web caching

- Differentiate between browser cache and cookies

- Explain the fundamentals of Modern HTTP (HTTP/2 & HTTP/3) and analyse their web performance

- Compare and contrast HTTP/2 vs HTTP/1.1

- Compare and contrast HTTP/2 vs HTTP/3

- Analyse web performance of hypothetical scenario with HTTP version 1.0, 1.1, 2, and 3.

- Describe Network Performance via Visual Illustration

- Draw the space-time diagram to illustrate the latency of downloading objects from web servers/web cache, depending on HTTP versions used.

These learning objectives aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of HTTP, including its fundamental concepts, communication models, connection types, URL structures, state management through cookies, and the role of web caching in enhancing web performance.

In this chapter we are going to discuss an “iconic” TCP reliant server: the HTTP.

HyperText Transfer Protocol

HTTP is an application-layer protocol used for transmitting hypertext documents on the World Wide Web. It is the foundation of any data exchange on the web and a protocol used for transmitting hypertext requests and information between clients and servers. It defines how messages are formatted and transmitted, and what actions Web servers and browsers should take in response to various commands.

The resources in the web that are transferred via the HTTP can be accessed by users by using web browsers (or other system programs like curl) and are published by a software application called a web server. The web and the internet might sound similar, but they have subtle differences. Read this appendix section if you want to find out more.

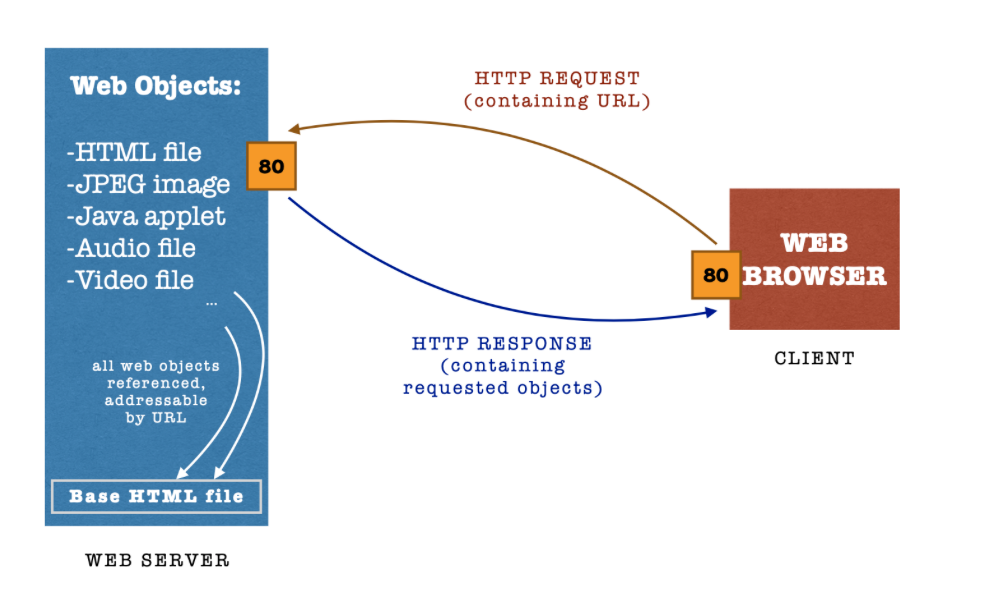

How the Web Works

The diagram below illustrates how the web works (simplified). We assume the classic static website experience.

A typical web page consists of Objects (files): HTML file, JPEG/PNG/SVG images, Java applet, video clip, etc, each that is addressable by URLs (Uniform Resource Locator).

URL

A URL is a reference or address used to access resources on the internet. It specifies the location of a resource as well as the protocol used to retrieve it.

Most web pages consist of a Base HTML File, which points you to these several referenced objects.

- For example, if a Web page contains

HTMLtext and 3 JPEG images, then the Web page has 4 objects: the base HTML file plus the 3 images. - The base HTML file references the other objects in the page with the objects’ URLs.

- Each URL has two components: the hostname of the server that houses the object and the object’s path in the Server.

When a client (e.g: web browser) initiates a connection to a web server, it will first request for the base HTML file for the Web Page in question. From then on, the client can request for more objects in the page using the URLs or even request for another page (go to another page).

The HTTP has a client/server model:

- Client: a browser that requests, receives (using HTTP protocol), and displays (render) Web objects

- Server: an application that sends (using HTTP protocol) Web objects in response to client requests.

The standard steps for HTTP protocol is as follows:

- Client initiates TCP connection (creates socket) to server at a given IP address, port 80

- Server accepts TCP connection from client, creates a socket with this particular client (remember TCP socket is a 4-tuple)

- HTTP messages (application-layer messages) exchanged between browser (HTTP client) and Web server (HTTP server)

- TCP connection closed at the end of the message / session

Example: Accessing http://example.org

Here’s a concrete example, linking it up with previous chapters (DNS and Socket): Entering the URL:

- The user types

http://example.orginto the web browser’s address bar and presses Enter.

DNS Resolution:

- The browser contacts a DNS server to resolve

example.orgto its corresponding IP address, e.g.,93.184.216.34.

Establishing a Connection:

- The browser initiates a TCP connection to the server at

93.184.216.34on port 80 (default port for HTTP).

HTTP Request:

- Once the connection is established, the browser sends an HTTP GET request to the server for the base HTML file.

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: example.org

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/90.0.4430.93 Safari/537.36

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Connection: keep-alive

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

HTTP Response:

- The server responds with the requested HTML file.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Thu, 09 May 2024 12:34:56 GMT

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

Content-Length: 1256

Connection: keep-alive

Server: ECS (dca/24DD)

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Example Domain</title>

</head>

<body>

<div>

<h1>Example Domain</h1>

<p>This domain is established to be used for illustrative examples in documents. You may use this

domain in literature without prior coordination or asking for permission.</p>

<p><a href="https://www.iana.org/domains/example">More information...</a></p>

</div>

</body>

</html>

Rendering the Page:

- The browser receives the HTML content and starts rendering the web page.

- If the HTML references additional resources (e.g., CSS, JavaScript, images), the browser will make subsequent HTTP requests to fetch those resources.

Breakdown of the Steps:

- User Input: The user enters a URL and initiates the process.

- DNS Resolution: The browser resolves the domain name to an IP address.

- TCP Connection: A connection is established to the server using the resolved IP address and appropriate port.

- HTTP Request: The browser sends an HTTP GET request for the base HTML file.

- HTTP Response: The server responds with the HTML content.

- Rendering: The browser renders the web page and requests additional resources as needed.

This example illustrates the process of accessing a web page from entering a URL to rendering the content in a web browser using HTTP. Typical web access these days relies on HTTPs (secure HTTP) with added encryption so that a malicious third party may not steal your information or collect data regarding your browsing habit. If you’re interested to read more about it, head to this appendix section.

HTTP Connection Types

There are two types of HTTP connection, persistent and non persistent.

Stateless

HTTP connections (both persistent and non persistent HTTP) are stateless. It means that each HTTP request from a client to a server is independent and unrelated to any previous request. The server does not retain any information about previous requests from the same client. Each request is processed as a new, unique transaction without any knowledge of prior interactions.

You can read more about this in the appendix to further appreciate the topic.

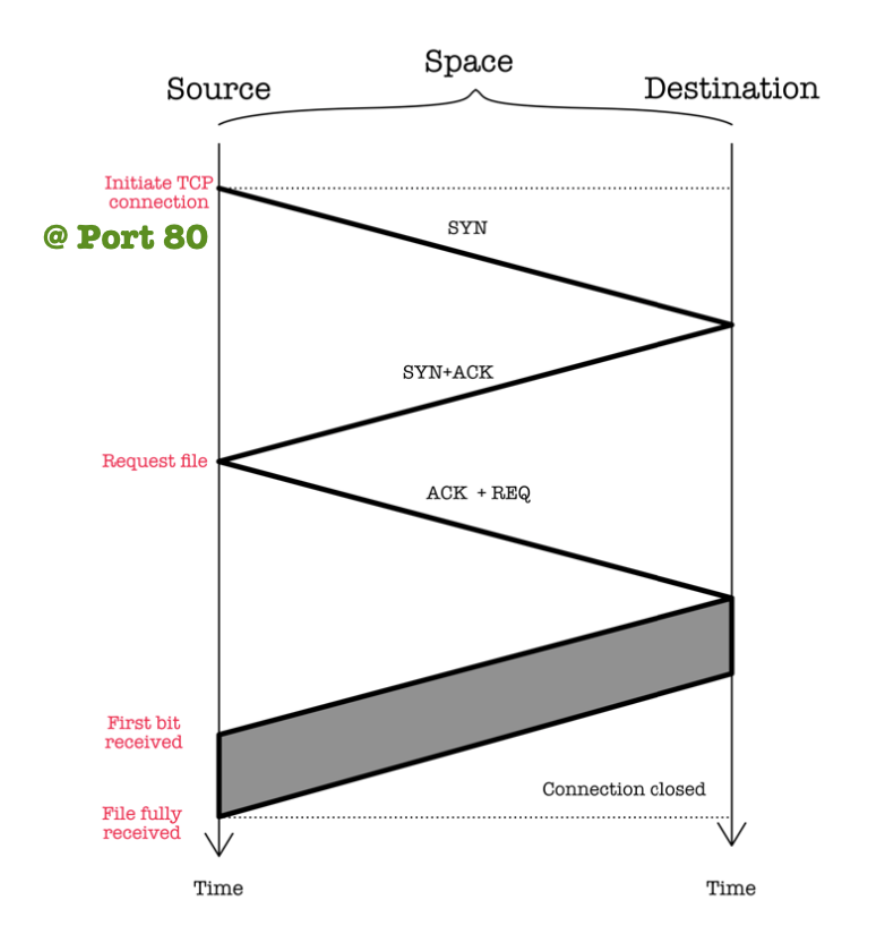

Non-Persistent HTTP (HTTP 1.0)

The space-time diagram below illustrates the nature of HTTP 1.0:

Characteristics:

- At most one object sent per TCP connection – and then connection is closed.

- Downloading multiple objects requires multiple connections.

- Requires 2 RTT per object + file transmission time, causing OS overhead for each TCP connection.

In practice, web browsers will open parallel (controlled degree of parallelism, e.g: N connections at a time) TCP connections to fetch referenced object. Browsers should be able to start retrieving other objects before completing retrieval of previous objects. This is more efficient than serial retrievals.

Parallel retrievals increases link utilization.

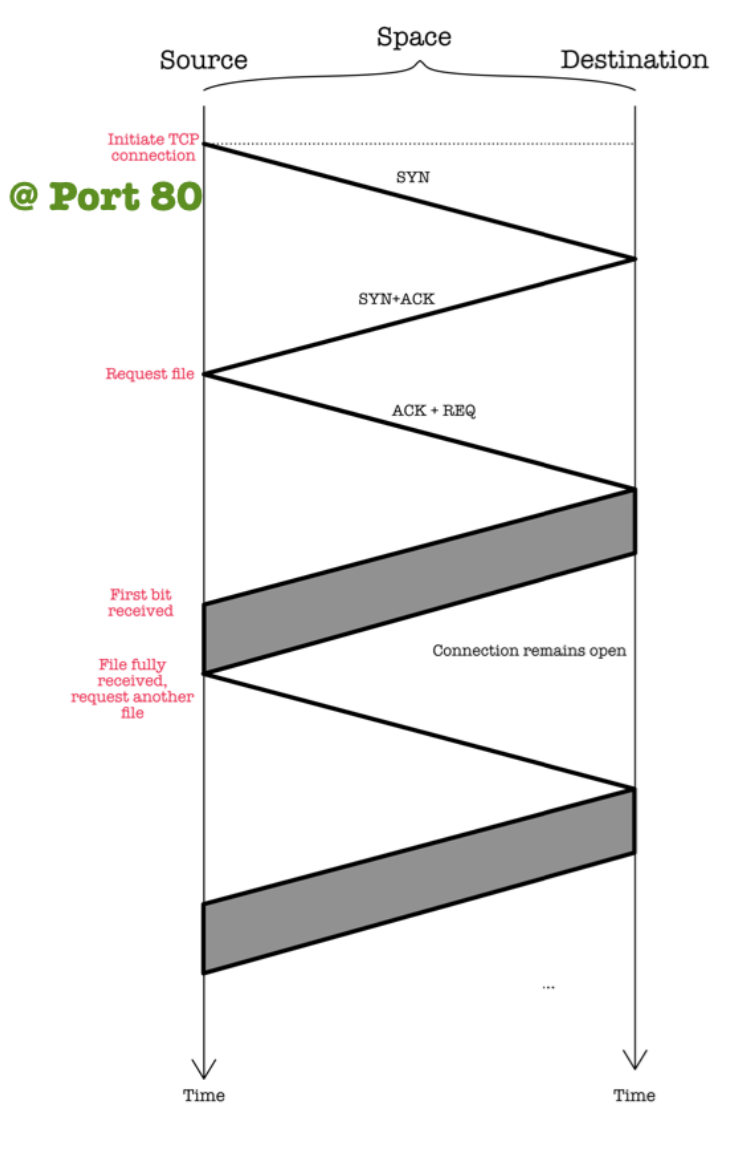

Persistent HTTP (HTTP 1.1)

The space-time diagram below illustrates the nature of HTTP 1.1:

Characteristics:

- Multiple objects can be sent over a single TCP connection between client and server as the server leaves connection open after sending response.

- Requires only 1 RTT to establish connection and 1 RTT + file transmission time per referenced object.

In practice, clients (e.g: web browsers) will do pipelining: initiate multiple outstanding HTTP requests within the same TCP connection. Clients are able to send requests as soon as it encounters a referenced object, there is no need to wait for the previous request to finish, thereby reducing latency and improving the overall efficiency of network communication by utilizing a single TCP connection more effectively. This can lead to faster page load times as it minimizes the delay between requests and responses.

Piggybacking ACK with HTTP REQ

Notice how the last ACK in the three-way handshake of TCP piggybacks a HTTP-GET request. This is not a TCP handshake requirement but specific to the application whereby the client has data ready to send immediately after the connection is established.

In some typical cases, like web browser establishing a connection to a web server, the client is usually ready to send an HTTP GET request right after the TCP handshake completes. The client might indeed piggyback the HTTP GET request with the final ACK in the three-way handshake, combining the ACK and the first data packet into one.

However, there are situations where the client might not immediately send data after the TCP connection is established such as Telnet connection setup, SSL/TLS handshake.

Space-Time Diagram

In this section, we visualise the series of connections made between a web client and a web server. Suppose a web client tries to access a website with 2 embedded image files of similar size.

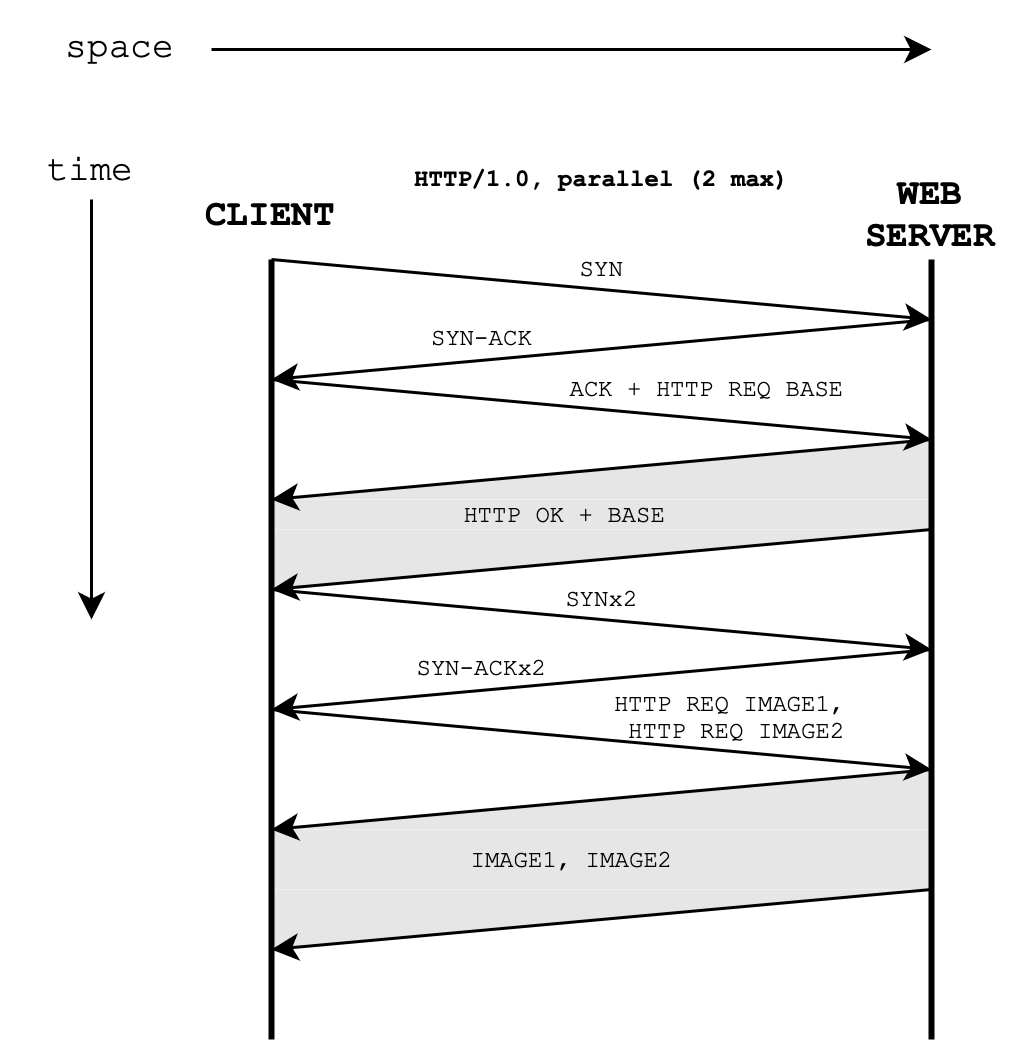

HTTP/1.0 with 2 Parallel Connections

Here’s the space-time diagram visualising the connection between the two parties if HTTP/1.0 is used with 2 parallel connections at maximum:

RTT + Transmission Time

If queueing and processing delays are negligible, the total time taken to load the webpage is 4 RTTs + Base HTML transmission time + 1 image object transmission time.

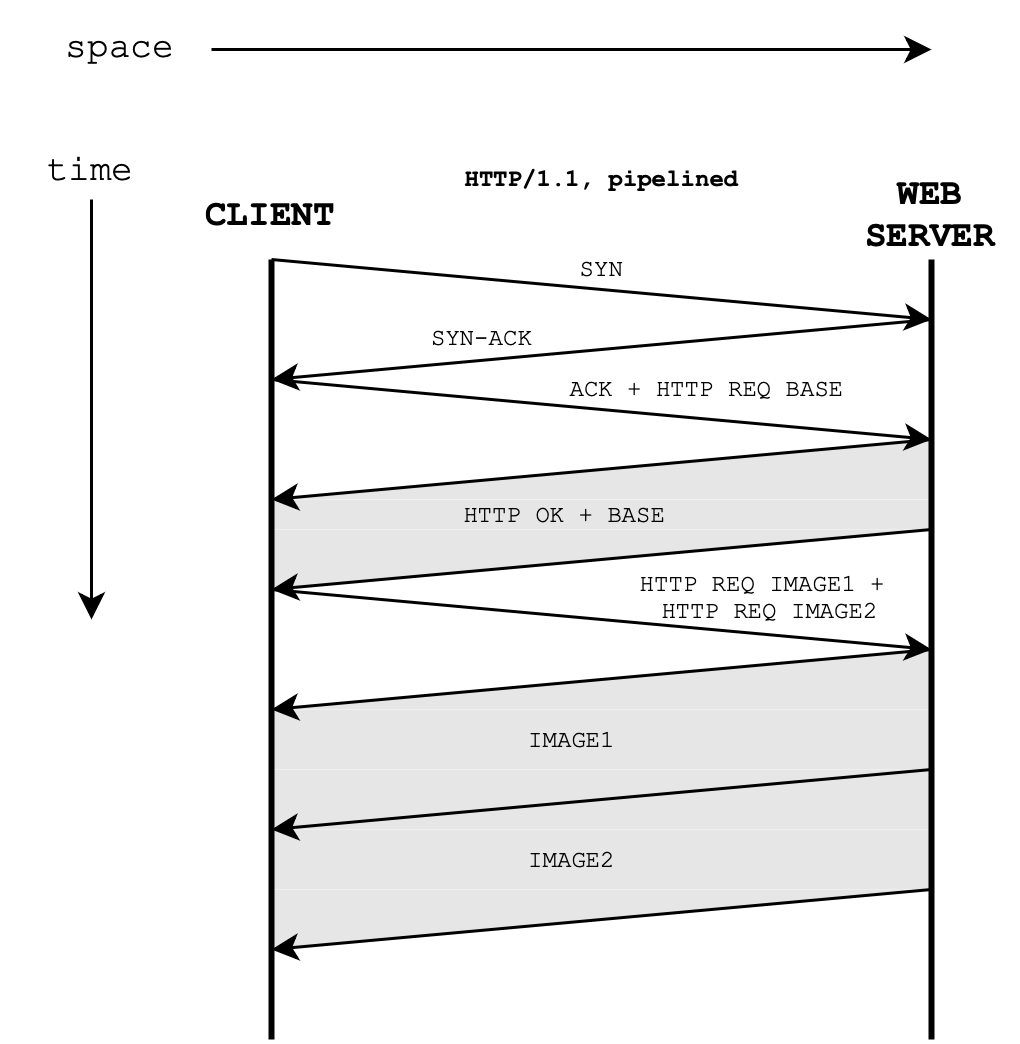

HTTP/1.1 with Pipelining

Here’s the space-time diagram visualising the connection between the two parties if HTTP/1.1 with pipelining is enabled:

RTT + Transmission Time

If queueing and processing delays are negligible, the total time taken to load the webpage is 3 RTTs + Base HTML transmission time + 2 * image object transmission time.

Comparison of Network Performance

HTTP/1.0 with parallel connections enabled allow for better throughput, but increased RTT. HTTP/1.1 with pipelined connection does not improve overall throughput, however it reduces total RTT. Each protocol has its pros and cons depending on the application scenario (e.g: if RTT is much longer than transmission time or not).

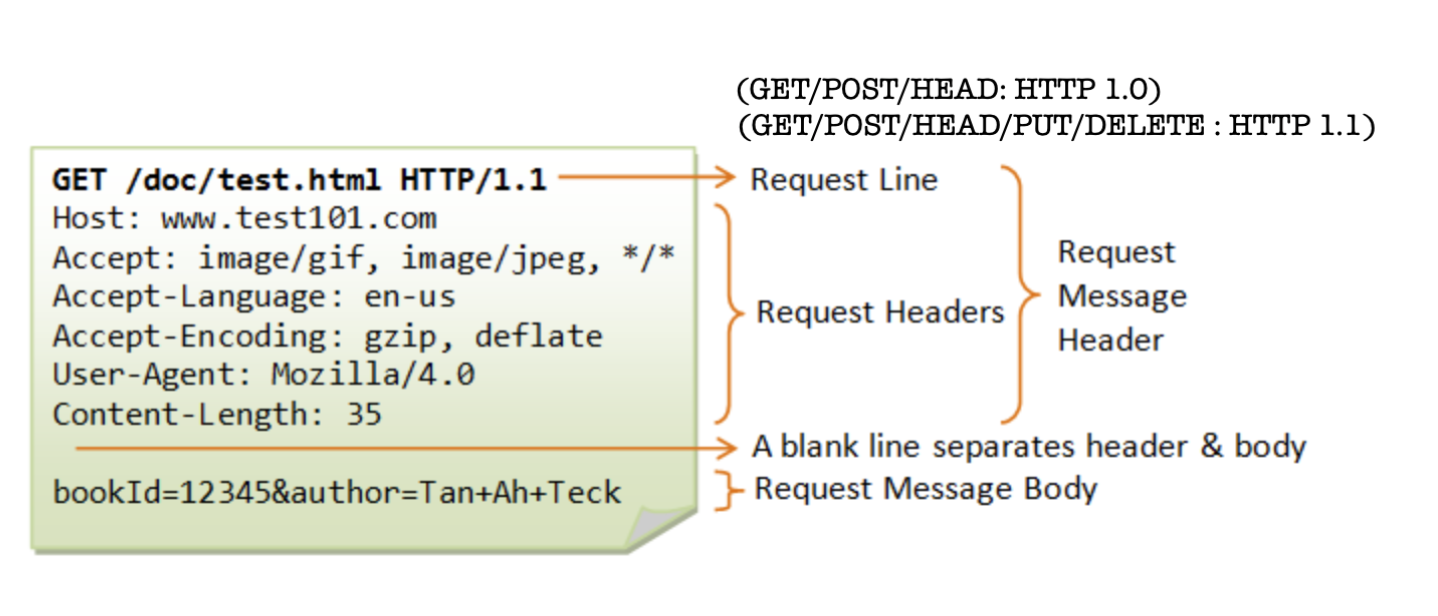

HTTP Message Format

HTTP clients like web browsers craft HTTP request messages intended for web servers depending on user interaction (e.g: drags, clicks, etc). The web server will inspect the request and return HTTP Response messages. The web browsers receiving the response will then render the response to display its content.

HTTP Request Message

The general format of a HTTP request message is as such:

Method types:

- HTTP 1.0:

GET,POST,HEAD(asks server to only return headers and leave requested object out of response) - HTTP 1.1:

GET,POST,HEAD,PUT(uploads file in entity body to path specified in URL field),DELETE(deletes file specified in URL field)

More details can be found here.

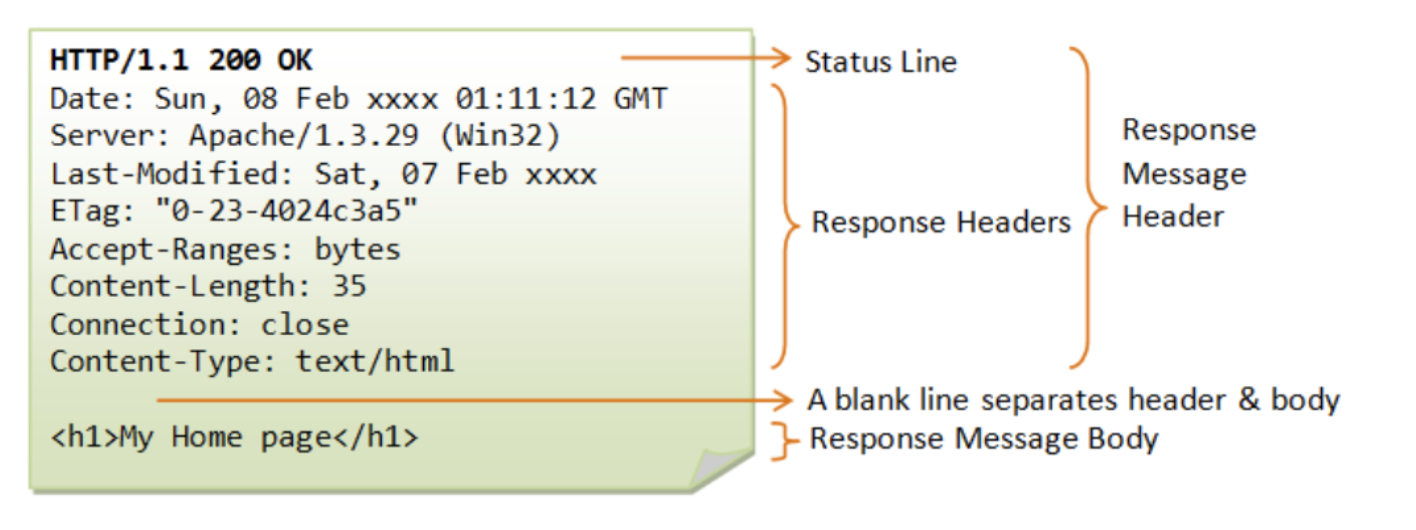

HTTP Response Message

The general format of HTTP response message is as such:

There are several common HTTP response status code: 200 (OK), 301 (Moved Permanently), 304 (Not Modified), 400 (Bad Request), 404 (Not Found), 505 (HTTP Version not Supported). Further details can be found here.

Secure HTTP (HTTPs)

HTTPs uses TLS (Transport Layer Security) or SSL (Secure Socket Layer) encryption. Web servers that support HTTPs will accept connections at port 443 by default. Almost all websites run on HTTPS now (that 🔒 symbol on ur browser). HTTPS is not a separate protocol, but refers to use of ordinary HTTP over an encrypted SSL/TLS connection.

As of 2024, HTTPS predominantly uses TLS (Transport Layer Security) as the underlying protocol to secure communications over the internet. TLS is the successor to SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) and provides robust encryption, integrity, and authentication.

Why use HTTPs?

- Intruders both malignant and benign exploit every unprotected resource (e.g: cross-site scripting) between your websites and users – they inject (contents like ads), intercept requests, redirects websites, etc

- Many intruders look at aggregate behaviours to identify users: people can learn who uses your websites and listen to sensitive information like login credentials

- HTTPS doesn’t just block misuse of your website. It’s also a requirement for many cutting-edge features and an enabling technology for app-like capabilities such as service workers.

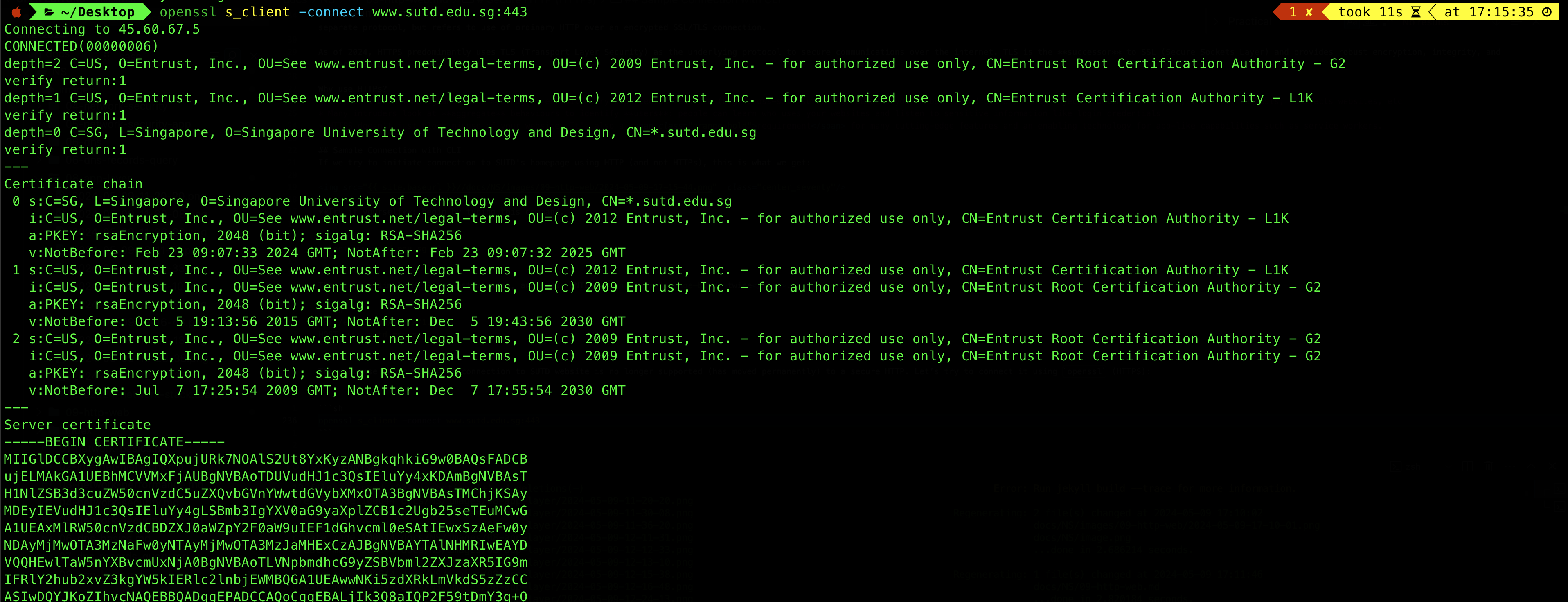

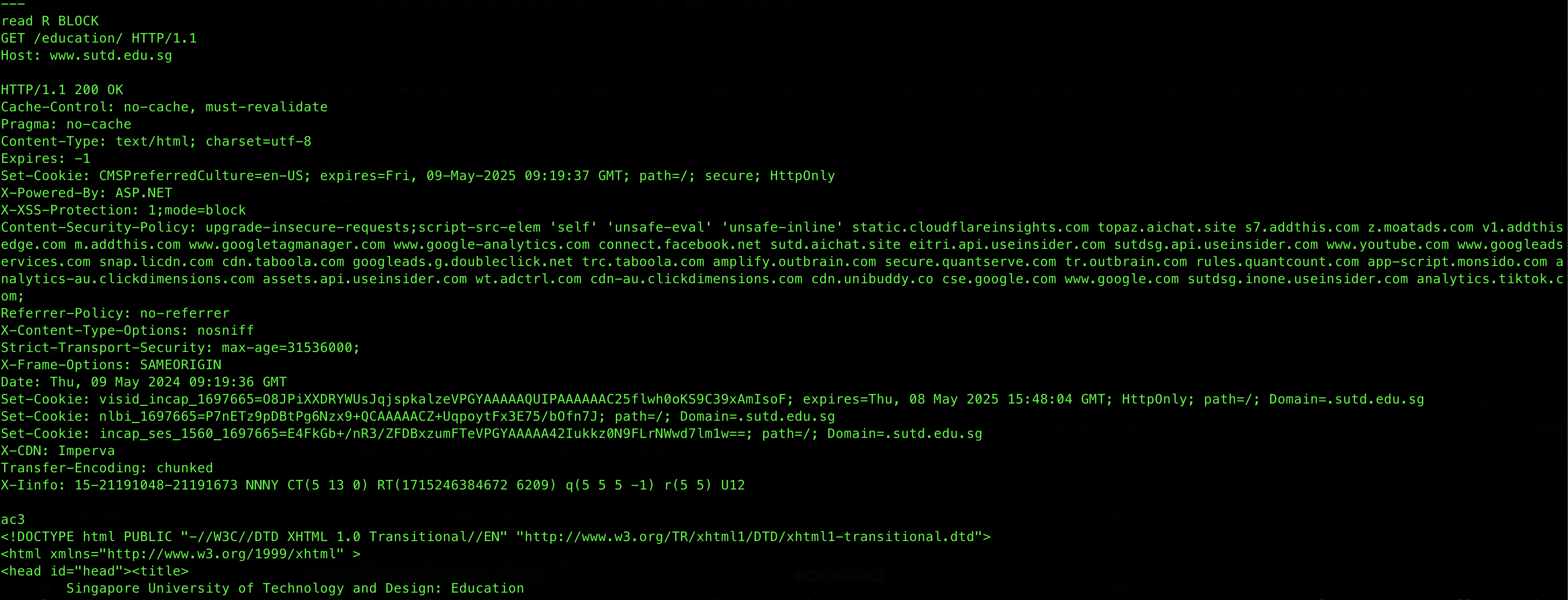

Sample Connection with CLI

If we try to initiate connection to SUTD’s homepage using HTTP (and not HTTPs), this is what we get:

Try it yourself: begin by typing this command,

telnet www.sutd.edu.sg 80

Then type a simple HTTP request message, and press ENTER twice. This indicates the end of the message.

GET /education/ HTTP/1.0

HOST: www.sutd.edu.sg

The response shows that HTTP connection to SUTD website is no longer supported (has moved permanently) to a secure HTTP. Let’s try to connect it using openssl (HTTPS):

openssl s_client -connect www.sutd.edu.sg:443

You will see SUTD’s certificate given as part of the connection handshake:

Afterwards, you can type the GET message as above. Don’t forget to press ENTER twice at the end.

GET /education/ HTTP/1.1

Host: www.sutd.edu.sg

The response is 200 OK, and the body below it shows a snippet of the html file requested from. Usually, it is interpreted by your browser and rendered. Note the part where there’s no cache, so all these are obtained from SUTD server and not local web cache:

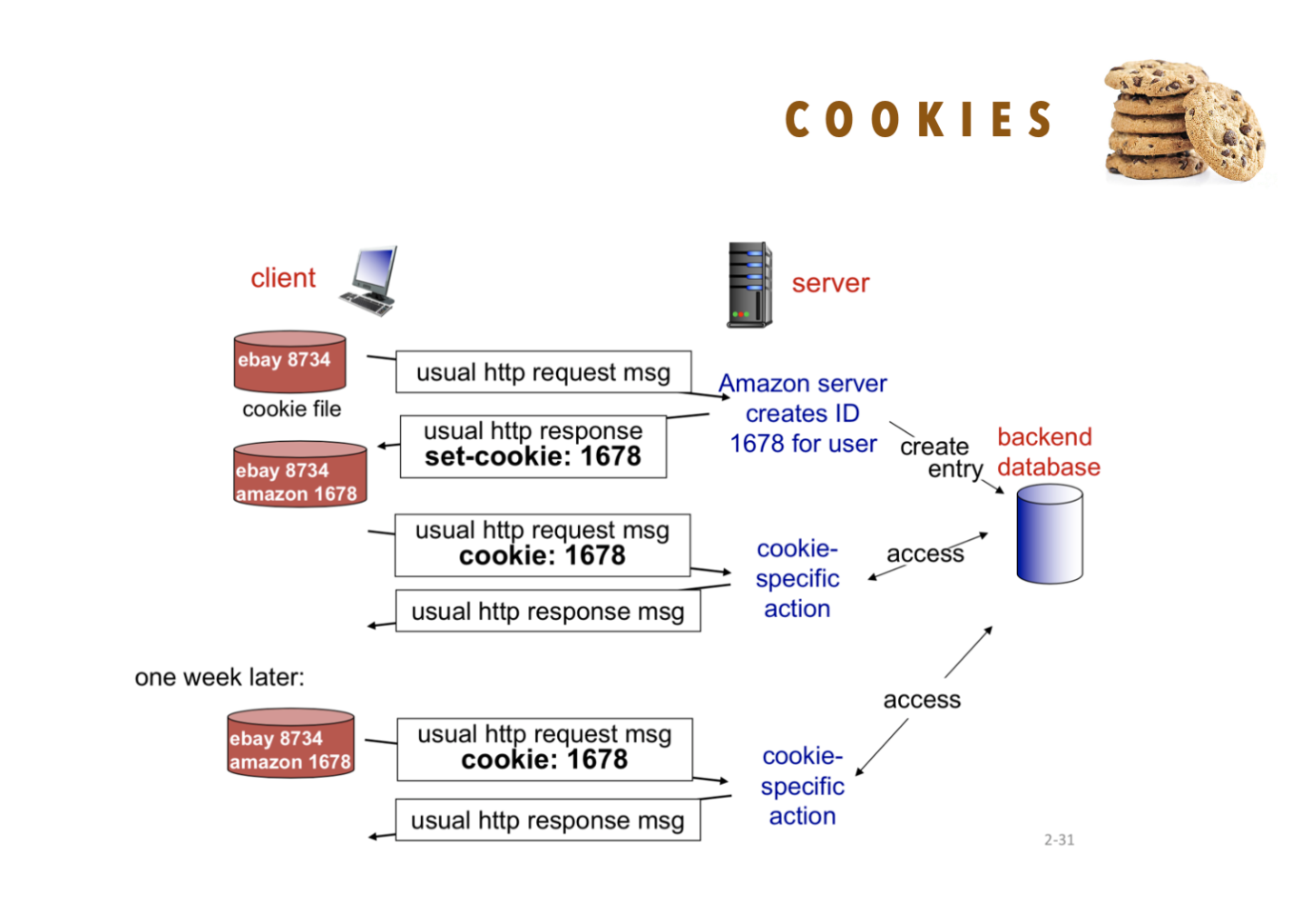

Cookies

HTTP connections are stateless by nature. However, sometimes we need to maintain some kind of states, such as to remain logged in when we browse a site, or to maintain or shopping cart from the day before. There are a few ways to keep these “states”:

- As cookies: http messages carry state

- As protocol endpoints: maintain state at sender/receiver over multiple transactions (alternative, more complicated)

Cookies

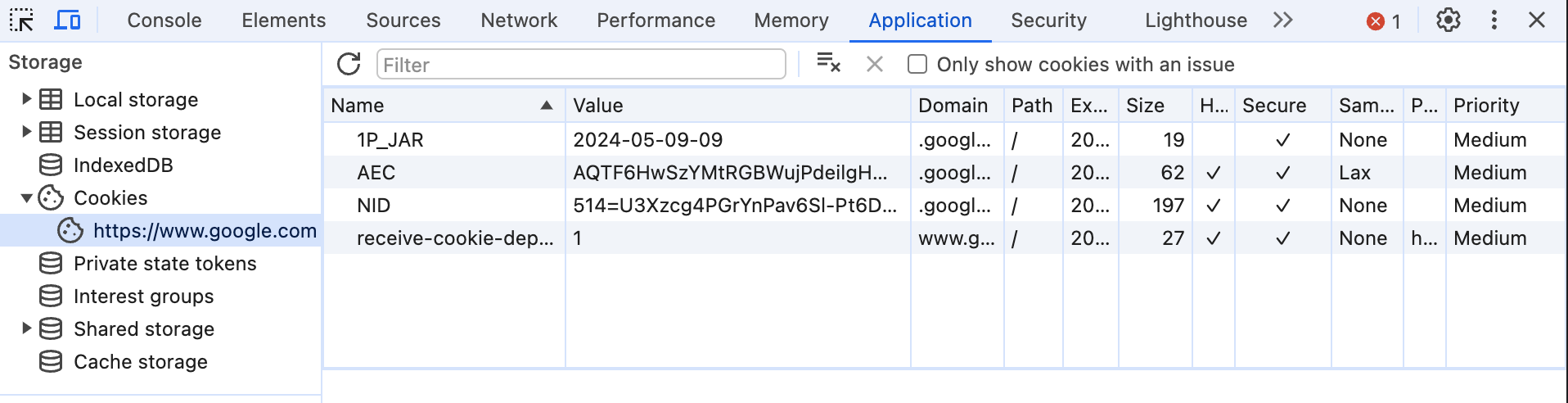

Cookies are small pieces of data stored on the client’s browser by websites. They are used to remember information about the user and their interaction with the site. Cookies are attached to HTTP requests sent to the site that set them.

You can easily inspect your browser cookies:

Cookies are also known as user-server states. In simple terms:

- A cookie is a small piece of data which is stored on the user’s computer.

- This cookie or small file gets attached to your browser while browsing. When a browser makes a request to a server, it includes the relevant cookies that were previously set by that server. This allows the server to recognize the user and maintain state across multiple requests.

- Essentially, websites use them to track information about your browsing habits and enable them to identify you upon further subsequent visits to their site.

Many websites use cookies to restore user state upon subsequent visits to the website (keeping you logged in). It can also be used to keep track of all the pages (of that site) visited from the moment a cookie is set, and in turn the site can recommend relevant things even when the client is not logged in or signed up at the site.

There are four components of cookies usage:

- Cookie header line in HTTP response message (cookies are set using the Set-Cookie HTTP header, sent in an HTTP response from the web server. This header instructs the client’s web browser to store the cookie).

- Cookie header line in next HTTP request message (automatically attached by client’s browser as long as the cookie is accessible by the destination’s site).

- Cookie file kept on user’s end, managed by user’s browser.

- Backend database at the server side that utilizes the cookie as index.

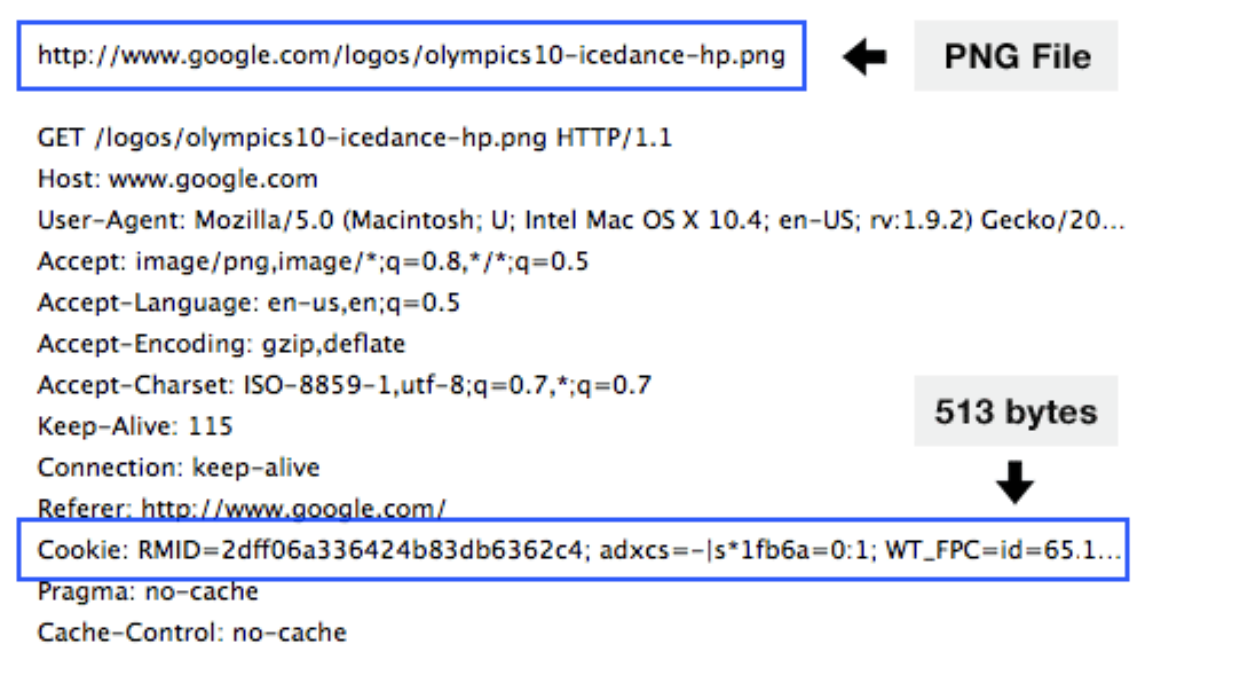

An example of Cookie header line in HTTP request message is shown below. Cookie is automatically attached in the HTTP request header by the browser as long as its accessible by the site:

Cookies can be used for many applications: login authorisation, maintaning shopping carts, enhancing recommendation system, and storing user-session state. Cookies also permit sites to learn a lot about you, such as your name, email address, and browsing pattern.

Risks

Cookie consent notices have become increasingly common due to various data protection and privacy regulations enacted around the world.

While cookies are essential for web functionality, they also pose certain risks and dangers, primarily related to security and privacy. The details are out of the syllabus, but you can read this appendix section for brief introduction.

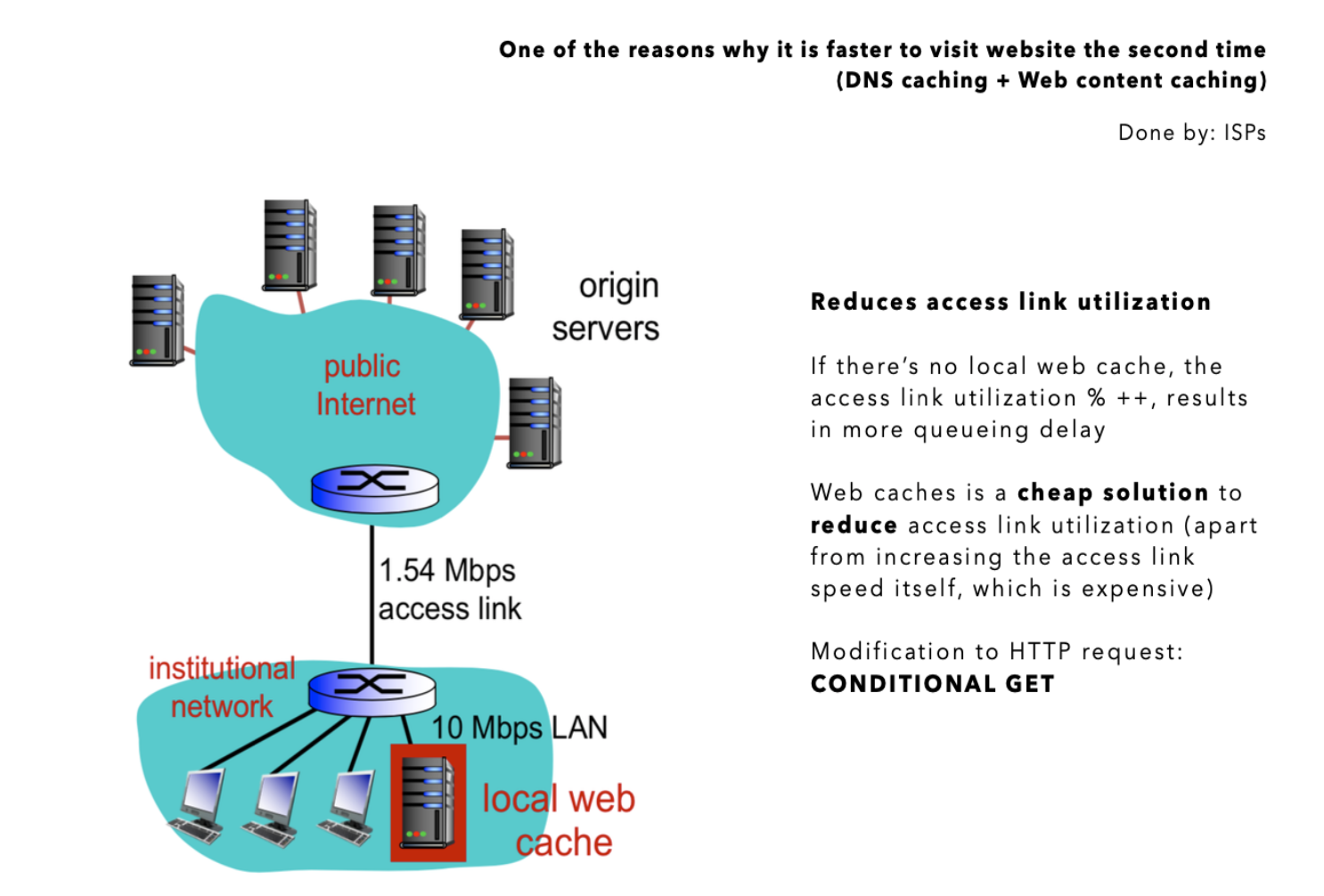

Web Cache

To reduce response time for client requests, many ISP installs web caches (also known as proxy). Our browser also helps to cache some web content. The idea is to help to reduce traffic on an institution access link. Web caches acts as both client and server:

- Web cache becomes a “server” for the original requesting client

- Web cache becomes “client” to origin server

The connection to local web cache typically has greater bandwidth as opposed to the public internet, due to proximity or simply better infrastructure in nearer locations. Hence using web caches reduces access link utilization (reduces the probability of queueing delay).

Conditional GET

A conditional GET is an HTTP request method that allows a client to make a request for a resource, but only if specific conditions are met. This method helps to reduce bandwidth usage and improve efficiency by avoiding the transfer of data that has not changed since the last access.

With conditional GET requests, servers do not send the requested objects again if cache has an up-to-date version (no transmission delay, less link utilization). The cache stores the date of cached copy in HTTP request. If the cache is not outdated, then the server’s response contains no object,

How would you draw the time-space diagram with web cache (proxy) involved between client and web server? The protocol used between client and web cache, and between web cache and web server can be different. For instance, HTTP/1.0 with 3 parallel connections max between proxy and web server, and HTTP/1.1 with pipelining between web client and web server.

Where are the caches?

Some of you might have heard that our web browser also caches content. This is correct. A Web Cache can be made of various players:

- On our own computer, managed by our browsers (we can clear this from our browser to save space)

- Local web caches provided by our ISP or institutions (e.g: SUTD)

When we open websites with large pictures and videos, it might take some time to load the website. The web browser can also store the site contents like the images, videos, audio etc. on our computer so that the next time we load the website, we can find loading of the webpage faster.

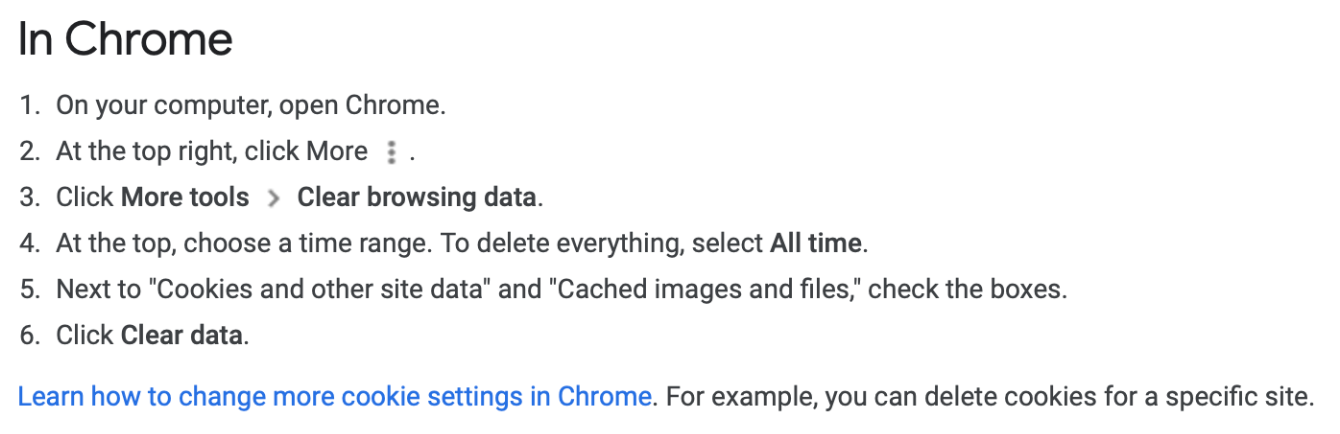

Browser Cache vs Cookies

Although both cache and cookies store some kind of data on a client’s computer, they are fundamentally different and they serve different purposes:

- Cookies are used to store information to track different characteristics related to a particular user (storing user preferences)

- Caches are used to make the loading of web pages faster (storing website content for future use).

- Cookies are files created by sites you visit. They make your online experience easier by saving browsing data (browsing session, temporary tracking data).

- The cache remembers parts of pages, like images, to help them open faster during your next visit (e.g: HTML files, related images, Javascript, CSS)

- Some cookies may automatically expire after some time

On the other hand, browser caches need to be manually cleared by us:

Practice

To thoroughly check your understanding regarding TCP, HTTP, the web and web caching, try to draw the space-time diagram for a client, a webserver, and a web cache, where the client requests 5 objects + HTML Base file via HTTP 1.1 (pipelining enabled) for all connections. You should draw the 3-way TCP Handshake between client and web cache, and web cache to the web server. You may assume that the 5 objects are of significant size (some latency is expected) as opposed to HTTP GET or TCP handshake.

Modern HTTP

Over time, HTTP has evolved into various versions. In this section, we briefly look into HTTP version 2 and 3, and analyse how they affect web performance.

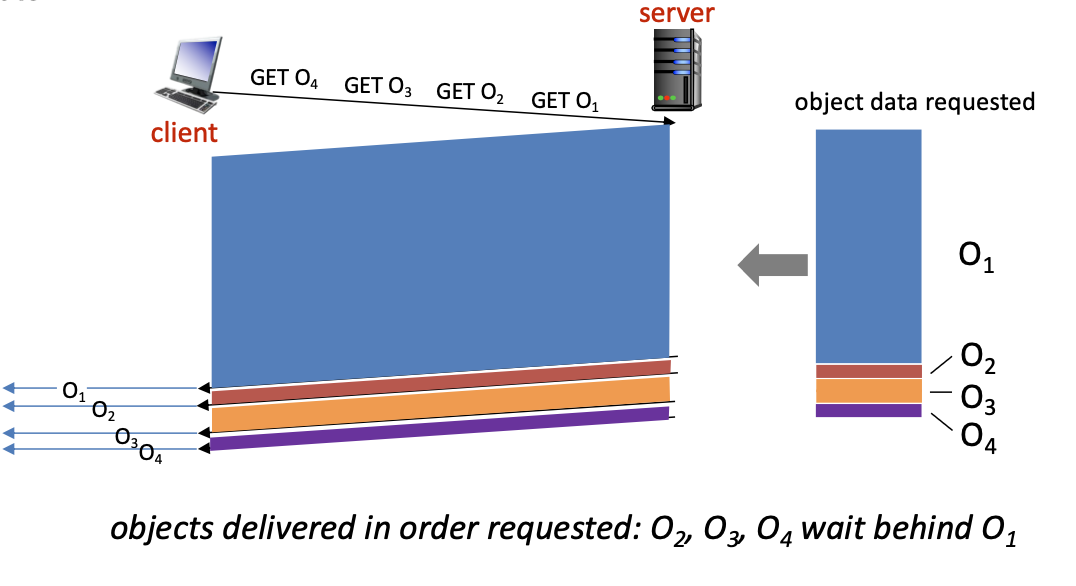

HTTP/1.1 Recap

HTTP/1.1 introduced multiple, pipelined GETs over single TCP connection/

The server responds in-order (FCFS: first-come-first-served scheduling) to multiple GET requests with FCFS. A a result, small object may have to wait for transmission behind large object(s). This is called head-of-line (HOL) blocking.

HOL Blocking

Head-of-line (HOL) blocking is a performance-limiting phenomenon that occurs when a line of packets is held up by the first packet, preventing others from proceeding. You may read this appendix section to find out more.

Furthermore, loss recovery measures (e.g: retransmitting lost TCP segments) stalls object transmission.

HTTP/2

HTTP/2, defined by RFC 7540, 2015, introduces increased flexibility for servers in sending objects to clients. Key features include:

- Unchanged Core Elements: Methods, status codes, and most header fields remain consistent with HTTP/1.1, ensuring compatibility and ease of transition.

- Client-Specified Object Priority: The server can transmit objects based on priorities specified by the client, rather than strictly following a First-Come, First-Served (FCFS) order. This allows for more efficient resource delivery.

- Server Push: The server can proactively push unrequested objects to the client, anticipating future requests and reducing latency.

- Frame Division and Scheduling: HTTP/2 divides objects into smaller frames, which are then interleaved and scheduled to mitigate Head-of-Line (HOL) blocking. This division and multiplexing improve the efficiency of data transfer over a single connection. A typical scheduling strategy will be round robin.

Round Robin

As the name suggests, this basic multiplexing strategy sends only one frame from each active object in each round. The number of active objects in each round may reduce over time because we have completed its transfer.

These features collectively enhance the performance and flexibility of HTTP/2 compared to HTTP/1.1, allowing for more efficient management of multiple objects and reducing delays in web communication.

HTTP/3

HTTP/3, defined by [RFC 9114, 2022], builds on the improvements of HTTP/2 while introducing several key differences and advantages:

-

Underlying Protocol: HTTP/3 is built on top of QUIC instead of TCP. QUIC, a transport layer protocol, combines the features of TCP, TLS, and HTTP/2 into a single protocol, providing faster connection establishment and improved performance.

-

Elimination of Head-of-Line (HOL) Blocking: QUIC uses UDP as its transport layer, enabling multiplexed streams to be independently managed. This eliminates the HOL blocking issue inherent in TCP-based HTTP/2, where packet loss in one stream affects all streams over the same connection.

-

Improved Connection Setup: QUIC reduces the connection setup time through 0-RTT (Zero Round Trip Time) and 1-RTT handshakes, allowing data to be sent immediately upon connection establishment. This leads to faster initial page loads compared to HTTP/2.

-

Better Loss Recovery and Congestion Control: QUIC implements more sophisticated loss recovery and congestion control mechanisms than TCP, leading to improved performance over unreliable networks.

-

Enhanced Security: QUIC integrates TLS 1.3 by default, providing robust security with reduced latency. HTTP/2 requires a separate TLS handshake over TCP.

Overall, HTTP/3 enhances performance, especially in high-latency and lossy network environments, by leveraging QUIC’s features. These improvements offer faster and more reliable web communication compared to HTTP/2.

Worked Example

In this section, we discuss in detail how HTTP/1.1 with pipelining, HTTP/2, and HTTP/3 handle sending multiple objects, focusing on Head-of-Line (HOL) blocking and how each protocol manages it, as well as its impact on web performance.

Suppose a server sends 4 objects under these conditions:

- Object 1: 1.5 MB (note: this is BYTE)

- Object 2: 100 KB

- Object 3: 200 KB

- Object 4: 300 KB

- Frame size: 100 KB (round robin manner)

- Network latency: 50 ms RTT

- Bandwidth: 10 Mbps (note: this is bit per second)

We would like to calculate the total time taken to receive each object from the moment the request to GET these objects are made (ignoring connection establishment).

First, calculate the time to transmit a single frame (a 100 KB frame):

HTTP/1.1 with Pipelining

Pipelining:

- Allows multiple

GETrequests to be sent over a single TCP connection without waiting for responses. - The server responds in order (FCFS: First-Come-First-Served).

HOL Blocking:

- Small objects may have to wait for large objects to be transmitted first.

- Example: If Object 1 (1 MB) is being sent, Objects 2-5 (100 KB each) must wait until Object 1 is fully transmitted.

- Loss recovery requires retransmitting lost TCP segments, stalling the transmission of other objects in the pipeline.

Time to transmit the objects:

- Sending requests:

- 1 RTT for the GET request: 50 ms

- Sequential responses due to FCFS:

- Object 1: 1200 ms (1500 KB / 10 Mbps)

- Object 2: 80 ms

- Object 3: 160 ms

- Object 4: 240 ms

Total time for HTTP/1.1: 50 ms + 1200 ms + 80 ms + 160 ms + 240 ms = 1730 ms**

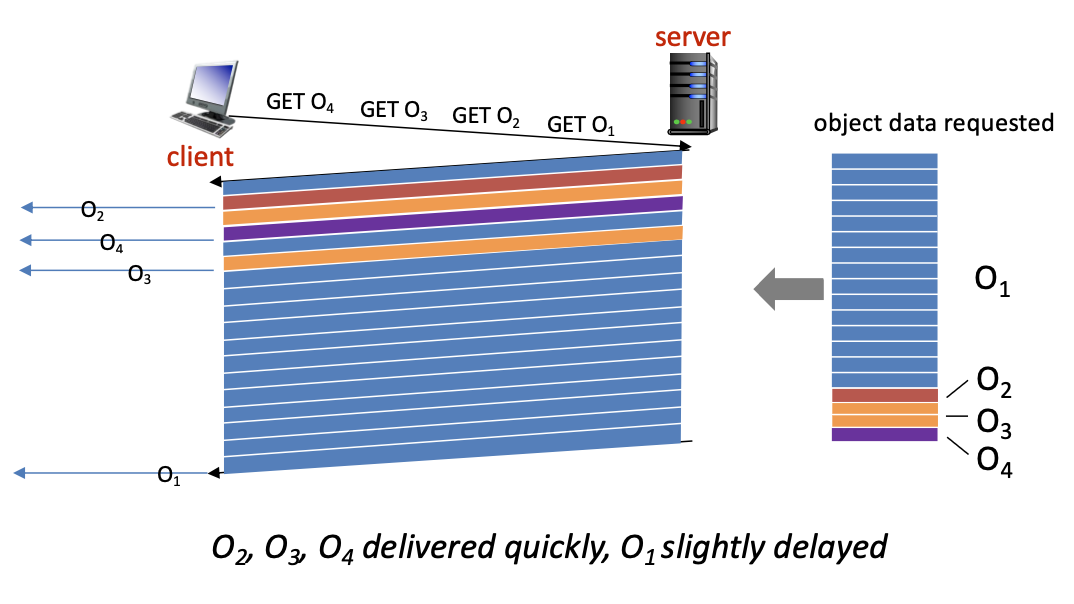

HTTP/2

Note: image for illustration purposes only, does not strictly accurately represent this current case study of O1 to O4 with this specific object size.

Multiplexing via Frame Division Scheduling:

- Allows multiple requests and responses to be sent concurrently over a single TCP connection.

- Uses streams to interleave data, mitigating application-level HOL blocking.

Improved Handling:

- Objects are divided into smaller frames, allowing interleaved transmission.

- Example: While Object 1 is being transmitted, parts of Objects 2-5 can be sent concurrently.

- However, TCP still introduces HOL blocking at the transport layer if packet loss occurs, as all streams share the same TCP connection.

Time to transmit the objects:

- Sending requests:

- 1 RTT for the GET request: 50 ms

- Concurrent transmission:

- Frames are interleaved using round-robin scheduling.

- Each frame is 100 KB, taking 80 ms to transmit.

- Total frames for each object:

- Object 1: 15 frames (1500 KB / 100 KB)

- Object 2: 1 frame (100 KB)

- Object 3: 2 frames (200 KB)

- Object 4: 3 frames (300 KB)

- Total frames for each object:

- Round-Robin Schedule: there are 4 objects per round

- Round 1: Frames from Object 1, Object 2, Object 3, Object 4 (4 frames)

- Round 2: Second frame from Object 1, 3, and 4

- Round 3: Third frame from Object 1 and 4

- Remaining rounds: all remaming frames of Object 1

Detailed Timeline:

- GET request: 50 ms

- First round of frames (4 frames, 100 KB each): 4 × 80 ms = 320 ms

- Frame 1 from Object 1: 80 ms

- Frame 1 from Object 2: 80 ms

- Frame 1 from Object 3: 80 ms

- Frame 1 from Object 4: 80 ms

- Second round of frames (3 frames, 100 KB each): 3 x 80 ms = 240 ms

- Frame 2 from Object 1: 80 ms

- Frame 2 from Object 3: 80 ms

- Frame 2 from Object 4: 80 ms

- Third round of frames (2 frames, 100 KB each): 2 x 80 ms = 160 ms

- Frame 3 from Object 1: 80 ms

- Frame 3 from Object 4: 80 ms

- Remaining frames for Object 1 (12 frames, 100 KB each): 12 × 80 ms = 960 ms

If we consider the time from the first GET as t=0:

- Objects 2 is fully received in the first round at t=210 ms

- Object 2: 50 ms (GET request) + 80 ms (object 1 frame 1) + 80 ms (object 2 frame) = 210 ms

- Object 3 is fully received in the second round: 370 ms + 80 ms (object 1 frame 2) + 80 ms (object 3 frame 2), at t = 530 ms

- Object 4 is fully received in the third round: 610 ms + 80 ms (object 1 frame 3) + 80 ms (object 4 frame 3), at t = 770 ms

- Since there’s no more other objects to send, we can focus on sending just Object 1 until completion. We have 12 frames remaining for Object 1 ever since Object 4 is completed:

- 770 ms + 12*80 ms = 1730 ms

Total time taken: 1730 ms, same as HTTP/1.1 due to bandwidth constraint, but we get to receive Object 2-4 way earlier. These objects can be rendered first in the browser.

HTTP/3

Built on QUIC:

- Uses UDP instead of TCP, eliminating TCP’s HOL blocking.

- Each stream is independently managed, so packet loss in one stream does not block others.

Enhanced Performance:

- No transport-level HOL blocking due to QUIC.

- Allows more efficient and reliable transmission, especially in high-latency or lossy networks.

Time to transmit the objects:

- Sending requests:

- 1 RTT for the GET request: 50 ms

- Concurrent transmission:

- Frames are transmitted concurrently without HOL blocking.

- Total data to send: 2.1 MB

- Time taken to transmit all data:

Total time for HTTP/3: also 1730 ms.

Summary of Differences

If we compute the time taken to receive the objects from the moment we sent GET request, then all methods seem to have the same performance:

- HTTP/1.1 with Pipelining: 1730 ms

- HTTP/2:

- Object 1: 1730 ms

- Objects 2-4: received after 210 ms, 530 ms, and 770 ms respectively

- HTTP/3: 1730 ms

Differences:

- HTTP/1.1 vs. HTTP/2: HTTP/2 allows smaller objects to be received much faster (e.g: 210 ms vs. waiting for the full 1730 ms in HTTP/1.1).

- HTTP/2 vs. HTTP/3: HTTP/3 is slightly faster compared to HTTP/2 if we consider the first TCP handshake as it eliminates the TCP handshake and transport-level HOL blocking, making it more robust in lossy or high-latency networks. However, if we consider the time taken to transmit the objects from the moment

GETrequest is made, then we end up with the same amount of transmission time as they’re limited by bandwidth.

Conclusion:

- HTTP/1.1 with Pipelining suffers from HOL blocking, making smaller objects wait for larger ones to finish.

- HTTP/2 uses frame division and round-robin scheduling to allow smaller objects to be received faster while still completing the transfer of the larger object efficiently.

- HTTP/3 further improves performance by eliminating transport-level HOL blocking, providing faster and more reliable data transfer overall.

HTTP/2 reduces delay by allowing interleaved transmission, but still suffers from TCP-level HOL blocking. HTTP/3 eliminates HOL blocking entirely, leading to the fastest performance.

Summary

This chapter explores HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol), a TCP-reliant server fundamental to web data exchange. HTTP, an application-layer protocol, enables the transmission of hypertext documents between clients and servers. Users access web resources through browsers or tools like curl, with these resources published by web servers.

A web page typically consists of multiple objects (e.g., HTML files, images) referenced by URLs. When a client (browser) connects to a server, it first requests the base HTML file, then fetches additional objects as needed. HTTP follows a client/server model, with clients requesting and displaying web objects and servers responding.

HTTP connections can be non-persistent (HTTP 1.0) or persistent (HTTP 1.1). Non-persistent connections handle one object per connection, leading to higher latency, while persistent connections allow multiple objects over one connection, improving efficiency and reducing latency through pipelining.

HTTP interactions involve standardized request and response formats with specific methods and status codes. HTTPS adds security via TLS/SSL encryption, protecting data and enabling advanced web features.

Cookies maintain state across stateless HTTP connections, storing user information for consistent experiences. However, cookies can pose security and privacy risks. Web caches enhance performance by storing frequently accessed content locally, using conditional GET requests to avoid redundant data transfers.

In summary, this chapter provides an essential overview of HTTP, covering web interactions, security enhancements, and efficiency mechanisms critical to web functionality.

Appendix

Internet vs Web

The Web:

- Definition: The World Wide Web (WWW), commonly referred to as the web, is a system of interlinked hypertext documents and multimedia content accessed via the internet.

- Components:

- Web Pages: Documents formatted in HTML (HyperText Markup Language) that can contain text, images, videos, and other multimedia, linked together via hyperlinks.

- Web Browsers: Software applications (e.g., Chrome, Firefox, Safari) used to access and navigate web pages.

- Web Servers: Computers that host web pages and provide them to clients (web browsers) upon request using HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol) or HTTPS (HTTP Secure).

- Function: The web allows users to access and interact with a vast array of content and services, including information, social media, e-commerce, and more.

The Internet:

- Definition: The internet is a global network of interconnected computers and other devices that communicate with each other using standardized protocols.

- Components:

- Networks: A collection of interconnected devices (computers, servers, routers, etc.) that share data and resources.

- Protocols: Rules and standards (e.g., TCP/IP) that define how data is transmitted and received over the network.

- Infrastructure: Physical components (e.g., cables, satellites, wireless systems) that enable connectivity and data transmission.

- Function: The internet facilitates the exchange of data and communication between devices worldwide, supporting various services such as email, file sharing, online gaming, and, notably, the World Wide Web.

Key Differences:

- The internet is the underlying global network infrastructure, while the web is a service that operates on top of this infrastructure.

- The internet includes various services beyond the web, such as email (SMTP), file transfer (FTP), and instant messaging.

In summary, the web is a vast collection of interconnected documents and multimedia content accessed via the internet, which is the global network enabling this and other forms of digital communication.

Web Browsing With HTTPs

Sure, here’s a concrete example of how HTTPS works, including details about the certificate exchange and symmetric key establishment.

Example: Accessing https://example.org

Entering the URL:

- The user types

https://example.orginto the web browser’s address bar and presses Enter.

DNS Resolution:

- The browser contacts a DNS server to resolve

example.orgto its corresponding IP address, e.g.,93.184.216.34.

Establishing a TCP Connection:

- The browser initiates a TCP connection to the server at

93.184.216.34on port 443 (default port for HTTPS).

TLS Handshake:

- The browser and server perform a TLS handshake to establish a secure connection.

Steps in the TLS Handshake:

- Client Hello:

- The browser sends a

Client Hellomessage to the server. This message includes information such as:

- Supported TLS versions

- Cipher suites (encryption algorithms) supported by the browser

- A randomly generated number (client random)

- The browser sends a

- Server Hello:

- The server responds with a

Server Hellomessage. This message includes:

- The selected TLS version

- The chosen cipher suite

- A randomly generated number (server random)

- The server responds with a

- Server Certificate:

- The server sends its digital certificate to the browser. The certificate contains the server’s public key and is signed by a trusted Certificate Authority (CA).

- Server Hello Done:

- The server sends a

Server Hello Donemessage to indicate it has finished its part of the handshake.

- The server sends a

- Client Key Exchange:

- The browser verifies the server’s certificate using the CA’s public key.

- The browser generates a pre-master secret (a random value) and encrypts it using the server’s public key from the certificate.

- The encrypted pre-master secret is sent to the server.

- Session Keys:

- Both the browser and server use the pre-master secret, along with the client random and server random, to generate the session keys (symmetric keys) for encrypting the session’s data.

- Client Finished:

- The browser sends a

Finishedmessage, encrypted with the session key, to indicate that the client part of the handshake is complete.

- The browser sends a

- Server Finished:

- The server sends a

Finishedmessage, encrypted with the session key, to indicate that the server part of the handshake is complete.

- The server sends a

Secure HTTP Request:

- With the secure connection established, the browser sends an HTTP GET request to the server for the base HTML file, encrypted with the session key.

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: example.org

(encrypted with session key)

HTTP Response:

- The server responds with the requested HTML file, encrypted with the session key.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Thu, 09 May 2024 12:34:56 GMT

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

Content-Length: 1256

Connection: keep-alive

Server: ECS (dca/24DD)

(encrypted with session key)

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Example Domain</title>

</head>

<body>

<div>

<h1>Example Domain</h1>

<p>This domain is established to be used for illustrative examples in documents. You may use this

domain in literature without prior coordination or asking for permission.</p>

<p><a href="https://www.iana.org/domains/example">More information...</a></p>

</div>

</body>

</html>

Rendering the Page:

- The browser decrypts the received HTML content using the session key and starts rendering the web page.

- If the HTML references additional resources (e.g., CSS, JavaScript, images), the browser will make subsequent HTTPS requests to fetch those resources, reusing the established secure connection.

Breakdown of the Steps:

- User Input: The user enters a URL and initiates the process.

- DNS Resolution: The browser resolves the domain name to an IP address.

- TCP Connection: A connection is established to the server using the resolved IP address and port 443.

- TLS Handshake: The browser and server perform a series of exchanges to establish a secure connection, including verifying the server’s certificate and generating session keys.

- Secure HTTP Request: The browser sends an encrypted HTTP GET request for the base HTML file.

- HTTP Response: The server responds with the encrypted HTML content.

- Rendering: The browser decrypts and renders the web page, requesting additional resources as needed over the secure connection.

This example illustrates how HTTPS ensures secure communication between a client and a web server, protecting the data exchange through encryption and certificate-based authentication.

Stateless HTTP

When we say that HTTP is stateless, it means that each HTTP request from a client to a server is independent and unrelated to any previous request. The server does not retain any information about previous requests from the same client. Each request is processed as a new, unique transaction without any knowledge of prior interactions.

Implications of HTTP Being Stateless:

- Independence of Requests:

- Each HTTP request is self-contained and carries all the necessary information for the server to process it.

- The server does not need to remember any state information between requests.

- Simplified Server Design:

- Servers do not need to manage and store session state information, which simplifies the design and implementation of web services.

- The server can handle each request in isolation, improving scalability and robustness.

- Challenges for State Management:

- Web applications often require maintaining state information across multiple interactions (e.g., user sessions, shopping carts).

- Mechanisms such as cookies, URL parameters, hidden form fields, and web storage are used to maintain state information on the client side and pass it back to the server with each request.

Mechanisms to Maintain State:

- Cookies:

- Small pieces of data stored by the client’s browser and sent with each HTTP request to the same server.

- Used to store session identifiers, user preferences, and other state information.

- URL Parameters:

- State information can be included in the URL query string.

- Example:

http://example.org/page?session_id=12345

- Hidden Form Fields:

- State information can be included in hidden fields within HTML forms.

- When the form is submitted, the state information is sent to the server.

- Web Storage:

- HTML5 provides localStorage and sessionStorage APIs for storing data on the client side.

- Data stored in localStorage persists across browser sessions, while data in sessionStorage is cleared when the page session ends.

Example to Illustrate Statelessness:

Initial Request:

- The user visits

http://example.org/login. - The browser sends an HTTP GET request to the server.

GET /login HTTP/1.1

Host: example.org

Server Response:

- The server responds with the login page HTML.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Login</title>

</head>

<body>

<form action="/login" method="post">

<input type="text" name="username" placeholder="Username">

<input type="password" name="password" placeholder="Password">

<button type="submit">Login</button>

</form>

</body>

</html>

Login Request:

- The user enters their credentials and submits the form.

- The browser sends an HTTP POST request with the form data.

POST /login HTTP/1.1

Host: example.org

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 38

username=johndoe&password=secret

Server Response:

- The server processes the login request, creates a session, and responds with a Set-Cookie header to store the session ID in the client’s browser.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Set-Cookie: session_id=abc123; Path=/

Content-Type: text/html

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Welcome</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Welcome, John Doe!</h1>

</body>

</html>

Subsequent Request:

- The user navigates to another page.

- The browser sends an HTTP GET request with the session ID cookie.

GET /dashboard HTTP/1.1

Host: example.org

Cookie: session_id=abc123

Server Response:

- The server uses the session ID from the cookie to retrieve the user’s session state and respond appropriately.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Dashboard</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Dashboard for John Doe</h1>

</body>

</html>

In summary, HTTP being stateless means that each request is independent, and the server does not retain any state information between requests. State management must be handled using mechanisms like cookies, URL parameters, hidden form fields, or web storage.

Malicious Usage of Cookies

While cookies are essential for web functionality, they also pose certain risks and dangers, primarily related to security and privacy. Here are some of the key dangers of cookies:

Security Risks:

- Cross-Site Scripting (XSS):

- Attackers can inject malicious scripts into web pages viewed by other users. If these scripts can access cookies, they may steal session cookies, which can lead to session hijacking.

- Mitigation: Use HttpOnly flag to prevent cookies from being accessed via JavaScript.

- Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF):

- Attackers can trick users into making unintended requests to a site where they are authenticated, using their cookies to perform actions on their behalf.

- Mitigation: Implement CSRF tokens and use the SameSite attribute on cookies.

- Session Hijacking:

- If session cookies are intercepted (e.g., via an insecure network), attackers can impersonate the user and gain unauthorized access to their session.

- Mitigation: Use Secure flag for cookies to ensure they are only sent over HTTPS, and implement session expiration and regeneration policies.

- Cookie Theft:

- Cookies can be stolen through various attacks, including man-in-the-middle attacks if data is transmitted over an unsecured connection.

- Mitigation: Always use HTTPS to encrypt data in transit.

Privacy Risks:

- Tracking and Profiling:

- Cookies can be used to track users across different websites, creating detailed profiles of their browsing habits, preferences, and behavior without their explicit consent.

- Mitigation: Use browser settings to block third-party cookies, and utilize privacy-focused browser extensions.

- Data Collection Without Consent:

- Websites may collect personal data through cookies without users’ knowledge or consent, which can be used for targeted advertising or sold to third parties.

- Mitigation: Comply with privacy regulations like GDPR and CCPA, and provide clear, accessible cookie consent mechanisms.

Other Risks:

- Storage Overload:

- Excessive use of cookies can lead to a large number of cookies being stored in the browser, which can degrade performance and user experience.

- Mitigation: Limit the number of cookies and their size, and use modern storage APIs where appropriate.

- Insecure Storage:

- Storing sensitive information in cookies can be risky, as they are not designed for secure data storage.

- Mitigation: Avoid storing sensitive data in cookies. Use secure server-side storage and session management.

Best Practices to Mitigate Cookie Risks:

- HttpOnly Flag:

- Prevents cookies from being accessed via JavaScript, reducing the risk of XSS attacks.

- Secure Flag:

- Ensures cookies are only sent over secure HTTPS connections, protecting them from being intercepted.

- SameSite Attribute:

- Controls whether cookies are sent with cross-site requests, mitigating CSRF attacks. Values include

Strict,Lax, andNone.

- Controls whether cookies are sent with cross-site requests, mitigating CSRF attacks. Values include

- Regularly Clean Cookies:

- Users should periodically clear cookies from their browsers to minimize tracking and potential security risks.

- Cookie Policy and Consent:

- Websites should implement transparent cookie policies and obtain user consent before setting cookies, in compliance with privacy regulations.

HOL Blocking

Head-of-line (HOL) blocking is a performance-limiting phenomenon that occurs when a line of packets is held up by the first packet, preventing others from proceeding. It can manifest in different layers of networking:

- TCP Layer:

- In TCP, packets are delivered in order. If a packet is lost, all subsequent packets must wait until the lost packet is retransmitted and received, blocking the flow of data.

- Application Layer:

- In HTTP/1.1, especially without pipelining, multiple requests and responses are handled sequentially. Even with pipelining, responses must be processed in order. If an earlier request takes longer to process, subsequent requests are delayed.

HOL Blocking in Different HTTP Versions

HTTP/1.1:

- Without pipelining, each request waits for the previous response to complete.

- With pipelining, multiple requests can be sent at once, but responses are processed in order. If one response is delayed, subsequent responses are also delayed.

HTTP/2:

- Uses multiplexing to send multiple streams over a single TCP connection. However, TCP itself can still experience HOL blocking at the transport layer. If a packet is lost, it blocks the entire TCP stream until the packet is retransmitted and received.

- While HTTP/2 mitigates HOL blocking at the application layer, it cannot eliminate TCP-level HOL blocking.

HTTP/3:

- Built on top of QUIC, which uses UDP instead of TCP.

- QUIC manages multiple streams independently. If a packet in one stream is lost, it does not block packets in other streams.

- This eliminates HOL blocking at both the application and transport layers, allowing more efficient and faster data transfer.

Impact on Performance

HTTP/1.1:

- Significant HOL blocking, leading to delays if any request or packet encounters issues.

HTTP/2:

- Reduced HOL blocking due to multiplexing, but still subject to TCP-level HOL blocking.

HTTP/3:

- Eliminates HOL blocking by using QUIC, providing faster and more reliable data transfer, especially in environments with packet loss.

By removing HOL blocking, HTTP/3 significantly improves performance, especially in high-latency or lossy network conditions.

50.005 CSE

50.005 CSE