- Operating System Design Structure

- System Programs

- Application (User) Programs

- System vs Application Programs

- OS Design and Implementation

- OS Structures

- Summary

- Appendix

50.005 Computer System Engineering

Information Systems Technology and Design

Singapore University of Technology and Design

Natalie Agus (Summer 2025)

Operating System Design Structure

Detailed Learning Objectives

- Describe Components of Modern Operating Systems

- Identify the roles of different components in a modern operating system: the kernel, system programs, and application programs.

- Identify System Programs

- Describe the function of system programs and their importance in providing a convenient environment for program development and execution.

- Explain how system programs operate in user mode and interact with the kernel through system calls.

- Categorize System Programs

- Examine various categories of system programs including package managers, status information tools, programming-language support, program loading and execution, communications, and background services.

- Distinguish Between System and Application Programs

- Differentiate between system programs (which facilitate operation of the hardware and system) and application programs (which perform user-oriented tasks).

- Explain the basic principles behind the design of OS Structure

- Compare and contrast between simple, layered, microkernel, and hybrid designs using examples such as macOS, JX, MSDos, and UNIX.

These objectives are aimed at providing a comprehensive understanding of the operating system’s architecture beyond the kernel, highlighting the crucial roles of system and application programs in enhancing user experience and system functionality.

Apart from the Kernel and the user interface (GUI and/or CLI), a modern operating system also comes with system programs and application programs.

Most users’ view of an operating system is defined by the system programs, not the actual system calls because they are actually hidden from us (through API).

For example, when a user’s computer is running the macOS, the user might see the GUI, featuring a mouse-and-windows interface.

System Programs

System programs, also known as system utilities, provide a convenient environment for program development and execution:

- They are basic tools used by many users for common low-level activities.

- These tools are very generic, thus can be considered as part of the “system” instead of individual user apps that we typically install

- Note that sometimes system programs and system calls have the same name, but they are nowhere the same. For example:

writeas a command that can be typed on the terminal (typeman writeto find out what these arguments are1.)writeis also a system call API and an actual system call name

System programs runs on user mode, just like any other user-level applications. When it requires kernel services, they make system calls just like any other user programs.

Categories

Like system calls, system programs can also be divided into the categories below.

Package Managers: file management and modification

These programs create, delete, copy, rename, print, dump, list, and generally manipulate files and directories. For example: all commands that you can enter in CLI that involves file management in UNIX systems is actually the name of system programs that can be found in the $PATH. These include ls, rm, mkdir, cp, touch among many others.

Modern OS usually comes with default package managers that simplifies installation of software applications (and also managing versions, updates, running background services, etc). For instance, brew for macOS and apt for Debian-based Linux distributions.

Several text editors provided (nano, vi) may be available to create and modify the content of files stored on disk or other storage devices. There may also be special commands to search the contents of files or perform transformations of the text like grep, awk, tr.

Status information

Some programs simply ask the system for various status information: date, time, amount of available memory or disk space, number of users, etc. Others are more complex, providing detailed performance, logging, and debugging information. Example include top, ls, df among many others.

Typically, these programs format and print the output to the terminal or other output devices or files or display it in a window of the GUI. Some systems also support a registry, which is used to store and retrieve system configuration information.

Programming-language support

Compilers, assemblers, debuggers, and interpreters for common programming languages (such as C, C++, Java, and Python) are often provided with the operating system or available as a separate download. Package managers such as npm, pip may be installed in modern OS to make it easier for users to develop.

Take these example of system programs with a grain of salt. The definitions of what program belongs to system program category is subject to debate. Some Operating Systems don’t come with compilers and debuggers so they may not be categorised as “system programs” for some.

Program loading and execution

Once a program is assembled or compiled, it must be loaded into memory to be executed. The system may provide absolute loaders, relocatable loaders, linkage editors, and overlay loaders. Runtime debugging systems for either higher-level languages or machine language are needed as well.

Communications

These programs provide the mechanism for creating virtual connections among processes, users, and computer systems. They allow users to send messages to one another’s screens, to browse Web pages, to send e-mail messages, to log in remotely, or to transfer files from one machine to another. Example include ssh, pipe (|).

Background services

All general-purpose systems have methods for launching certain system-program processes at boot time (upon startup): network-related system programs, some device drivers (although there are drivers that run in kernel mode, these are not system programs), etc

- Constantly running system-program processes are known as services, subsystems, or daemons.

- One example is the network daemon:

- A system needed a service to listen for network connections in order to connect those requests to the correct processes.

- Other daemon examples include:

- The

initprocess (specifically calledsystemdin Linux,launchdin macOS) - Process schedulers that start processes according to a specified schedule,

- System error monitoring services,

- Print servers

- The

Typical systems have dozens of daemons. In addition, operating systems that run important activities in user mode rather than in kernel mode may use daemons to run these activities.

Application (User) Programs

Along with system programs, most operating systems are supplied with programs that are useful for specific users. Such application programs are Web browsers, word processors and text formatters, spreadsheets, database systems, compilers, plotting and statistical-analysis.packages, and games.

System vs Application Programs

It is often hard to distinguish between system and application (user) programs. Some programs like compiler, assembler, debugger, device drivers, and antivirus can be clearly defined as system programs. Programs like media player, photo editing software applications, and video games are clear examples of application programs.

The table below summarises the differences between system programs and application programs (user programs).

| System Programs | User Programs |

|---|---|

| Used for operating computer hardware and very common system-usage purposes | Used to perform specific user-related tasks |

| Typically comes with the OS | Installed according to user requirements |

| Commonly runs in the background, require minimal to no user interactions | Requires interactions with users |

OS Design and Implementation

There’s no known ultimate solution when it comes to OS design. Internal structures of known operating systems can vary widely.

When one design an OS, it might be helpful to consider a few standard things listed below.

User and System Goals

Start by defining goals:

- User goals: OS should be convenient to use, easy to learn, reliable, safe, fast

- System goals: The system should be easy to design, implement, and maintain; and it should be flexible, reliable, error free, and efficient.

Policy and Mechanism Separation

One of the learning objectives of this chapter is to recognise the difference between policy and mechanism and separate them:

- Policy: determines what will be done

- Mechanism: determines how to do something

Policy vs. mechanism separation is a fundamental principle in operating system (OS) design. It aims to improve flexibility, maintainability, and adaptability of the system by decoupling the high-level decisions (policies) from the low-level implementations (mechanisms).

The separation of policy and mechanism is important for flexibility:

Mechanism

Mechanisms are the low-level operations or functions provided by the OS that enable the performance of basic tasks. They are the building blocks used to implement various policies. Mechanisms define how something is done, such as:

- Context Switching: How the OS switches between different processes or threads.

- Memory Management: How memory is allocated, accessed, and deallocated.

- File System Operations: How files are created, read, written, and deleted.

- Synchronization Primitives: How locks, semaphores, and other synchronization tools are implemented.

Policy

Policies are the high-level strategies or rules that govern the behavior of the system. They define what should be done under certain conditions and can be modified without changing the underlying mechanisms. Examples include:

- Scheduling Policy: Which process or thread should be executed next (e.g., round-robin, priority-based, fair scheduling).

- Memory Allocation Policy: How memory is allocated to different processes (e.g., first-fit, best-fit, worst-fit).

- Access Control Policy: Who is allowed to access specific resources and in what manner (e.g., user permissions, role-based access control).

- Page Replacement Policy: Which page should be swapped out when memory is full (e.g., LRU, FIFO).

Benefits of Separation

- Flexibility: Different policies can be implemented without altering the underlying mechanisms. This allows the OS to adapt to various requirements and workloads.

- Modularity: By separating policies from mechanisms, the system becomes more modular. This enhances code readability and maintainability.

- Reusability: Mechanisms can be reused across different policies, reducing redundancy and improving consistency.

- Ease of Updates: Policies can be updated or replaced to improve performance or add new features without changing the core mechanisms.

Example

Consider a process scheduling system in an OS:

- Mechanism: The OS provides mechanisms to maintain a ready queue of processes, context switch between processes, and track process states.

- Policy: The OS decides which process from the ready queue should be executed next. This could be based on a round-robin policy, priority-based scheduling, shortest job first, etc.

If a new scheduling policy needs to be implemented (e.g., a new priority-based algorithm), only the policy module needs to be updated or replaced. The underlying mechanisms for managing the ready queue and performing context switches remain unchanged.

Why separation between policy and mechanism is important

The separation of policy and mechanism in OS design is a key principle that enhances the system’s adaptability, maintainability, and flexibility. By keeping the high-level decision-making (policies) separate from the low-level implementations (mechanisms), operating systems can efficiently cater to diverse and changing requirements.

- Policies are likely to change across places or over time.

- In the worst case, each change in policy would require a change in the underlying mechanism.

A general mechanism insensitive to changes in policy would be more desirable. A change in policy would then require redefinition of only certain parameters of the system.

Take another example: a mechanism for giving priority to certain types of programs over others. If the mechanism is properly separated from policy, it can be easily tweaked based on user requirements:

- Support a policy decision that I/O-intensive programs should have priority over CPU-intensive ones

- Or support the opposite policy whenever appropriate.

Either way, no change in the instructions need to be made.

OS Structures

Once an operating system is designed, it must be implemented. Because operating systems are collections of many programs: kernel, system programs, interface, etc, written by many people over a long period of time, it is difficult to make general statements about how they are implemented2.

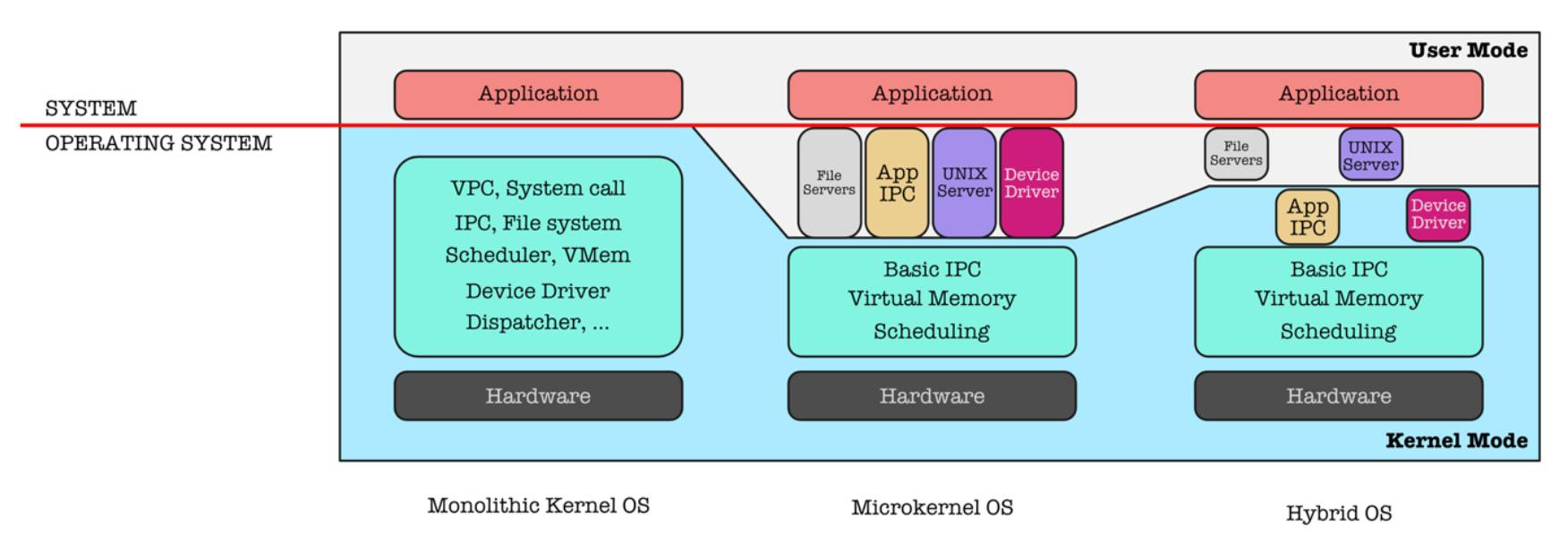

Below are a few common OS structures.

Monolithic Structure

A monolithic kernel is an operating system architecture where the entire operating system is working in kernel space. It can operate with or without dual mode.

Without Dual Mode

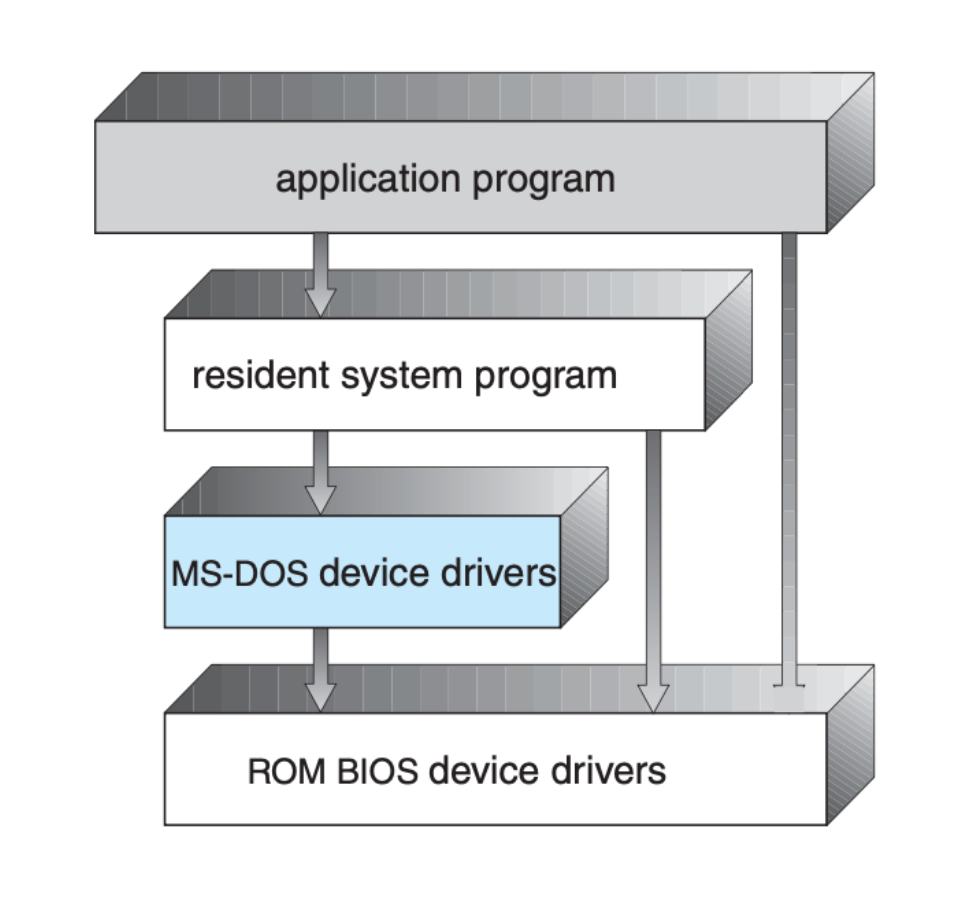

The figure below (screenshot from SGG book) shows the structure of MS-DOS, one of the simplest OS made in the early years:

- The interfaces and levels of functionality are not well separated (all programs can access the hardware) - i.e: at the time, MS-DOS was written for the Intel 8088 architecture, which has no mode bit and therefore no dual mode.

- For instance, application programs are able to access the basic I/O routines to write directly to the display and disk drives.

- Such freedom leaves MS-DOS vulnerable to errant (or malicious) programs, causing entire system crashes when user programs fail.

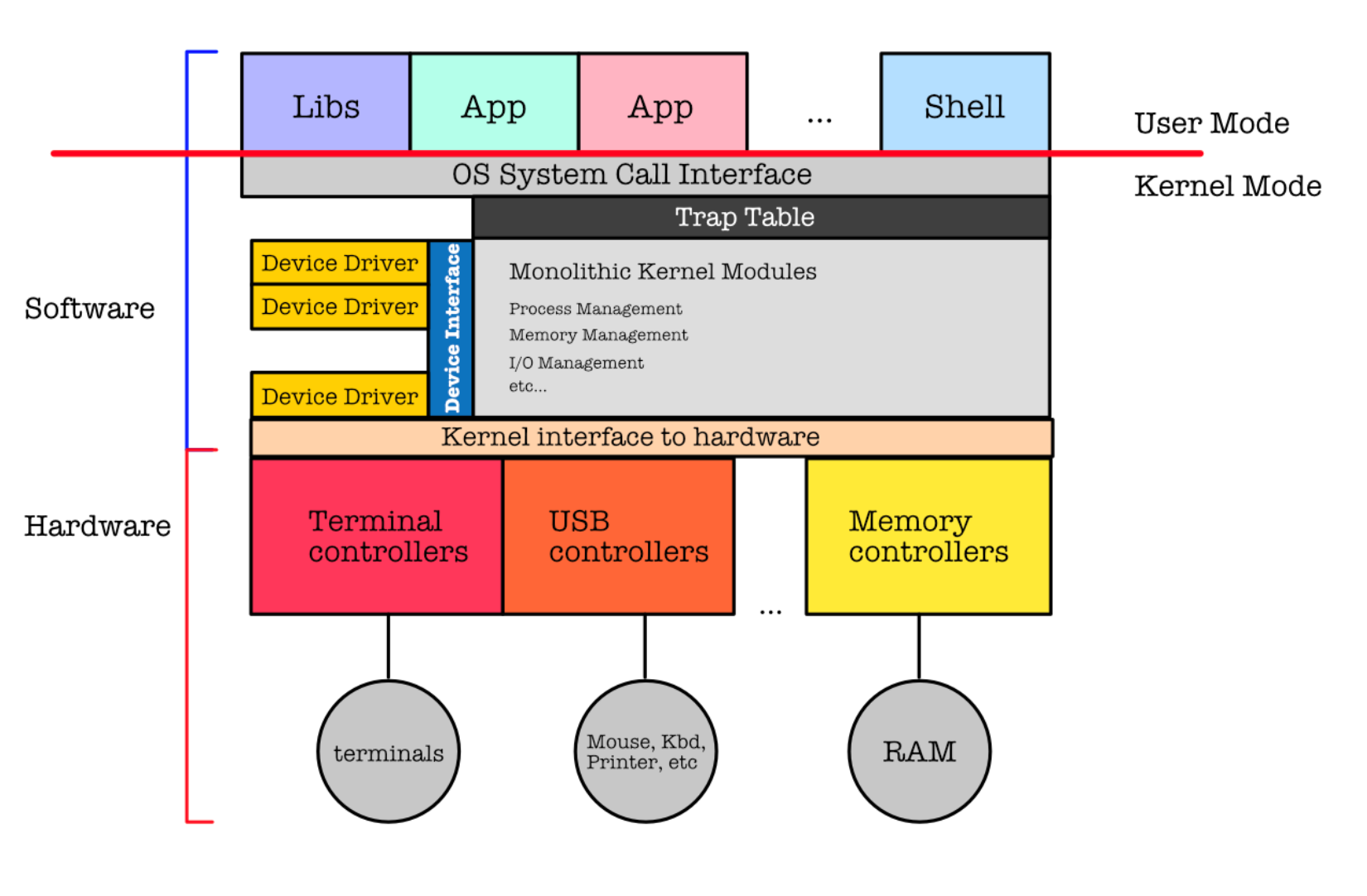

With Dual Mode

The early UNIX OS was also simple in its form as shown below. In a way, it is layered to a minimal extent with very simple structuring.

The kernel provides file system management, CPU scheduling, memory management, and other operating-system functions through system calls. That is an enormous amount of functionality to be combined into one level.

- Pros: distinct performance advantage because there is very little overhead in the system call interface or in communication within the kernel.

- Cons: difficult to maintain.

Other examples of monolithic OS with dual-mode: BSD, Solaris

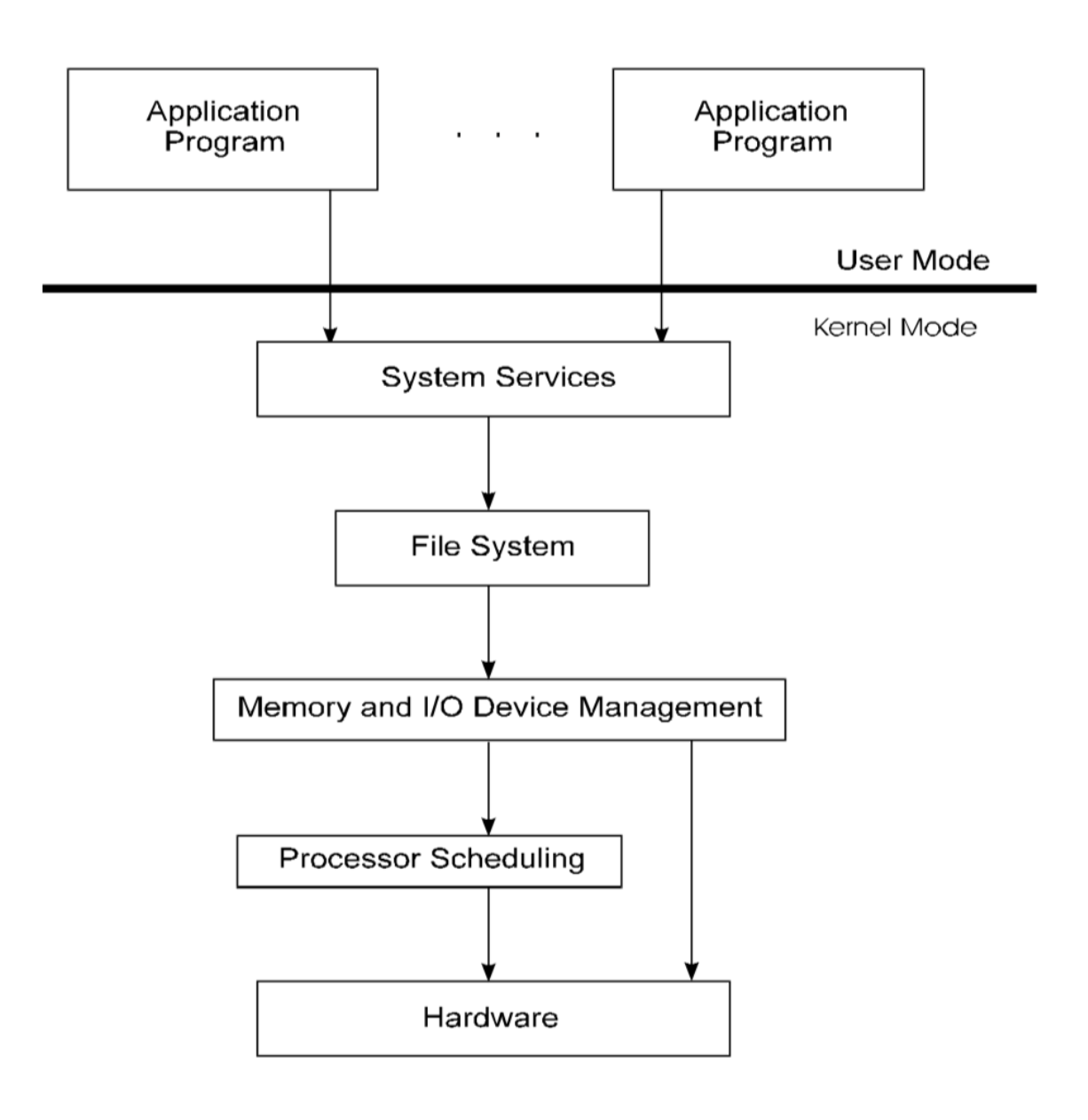

Layered Approach

The operating system is broken into a many number of layers (levels). The bottom layer (layer 0) is the hardware; the highest (layer N) is the user interface. The figure below shows a layered approach (layer names for illustration purposes). The programs in layer N rely on services ONLY from the layer below it.

Pros:

- Simple to construct and debug

- Each layer is implemented only with operations provided by lower-level layers.

- A layer does not need to know how these operations are implemented; it needs to know only what these operations do.

- This abstracts and hides the existence of certain data structures, operations, and hardware from higher-level layers.

Cons:

- Extra need to appropriately define the various layers, and careful planning is necessary.

- If we are met with bugs in our program, we debug our program and not our compiler

- We mostly assume that the layers beneath us are already made correct

- Sometimes, this assumption is not always true and difficult to maintain with the growing size of the OS. Some OS is shipped with bugs on its lower layers that are very difficult for users to debug.

- Patches and updates are periodically given to fix these bugs.

- They tend to be less efficient than other types.

- For instance, when a process running in user mode executes an I/O operation, it executes a system call that is trapped to the I/O layer, which calls the memory-management layer, which in turn calls the CPU-scheduling layer, which is then passed to the hardware.

- At each layer, the parameters may be modified, data may need to be passed, and so on.

- Each layer adds overhead to the system call.

- The net result is a system call that takes longer than does one on a non layered system.

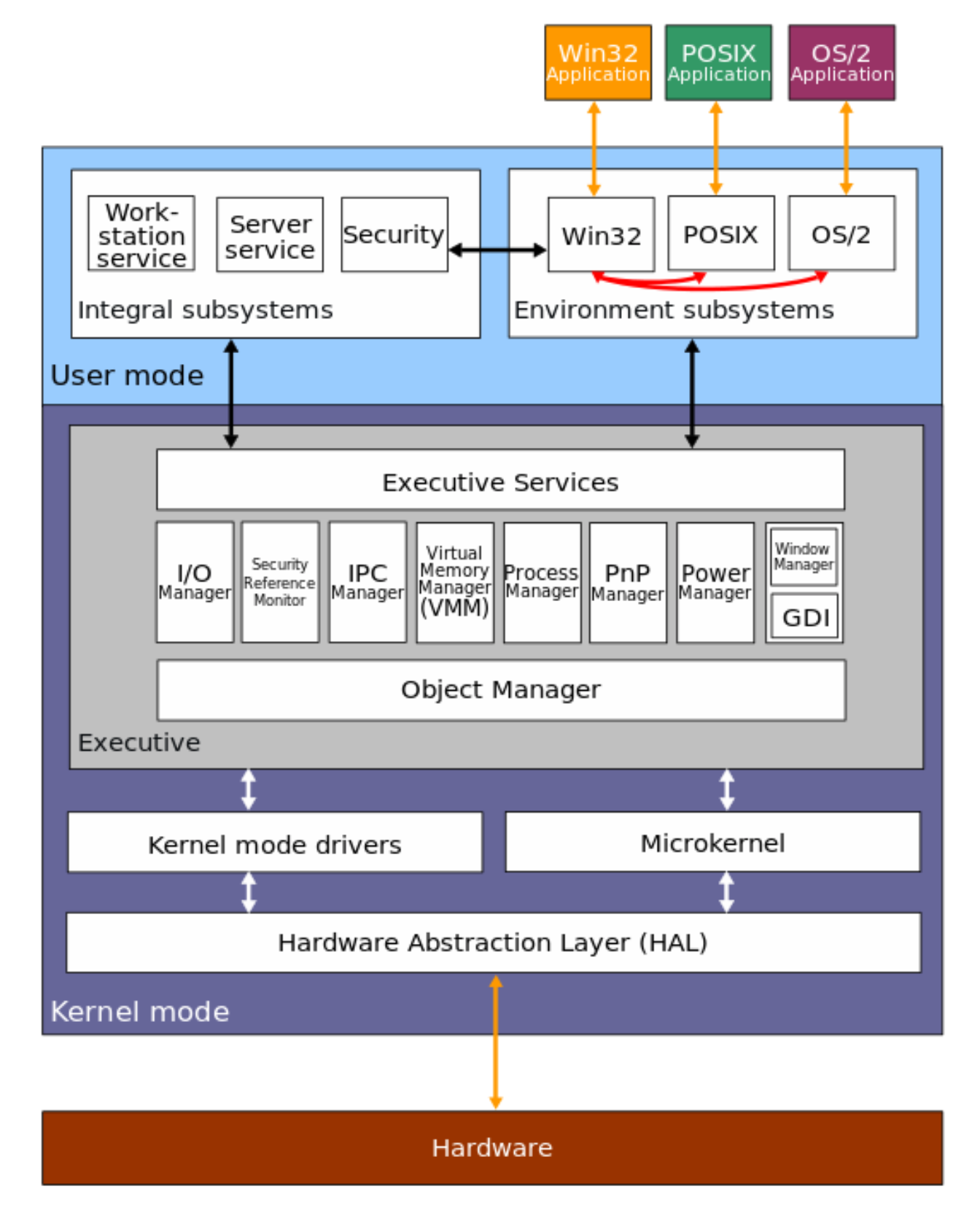

Example: Windows NT (the later version is actually a hybrid OS, combining between layered and monolithic aspects and benefits)3

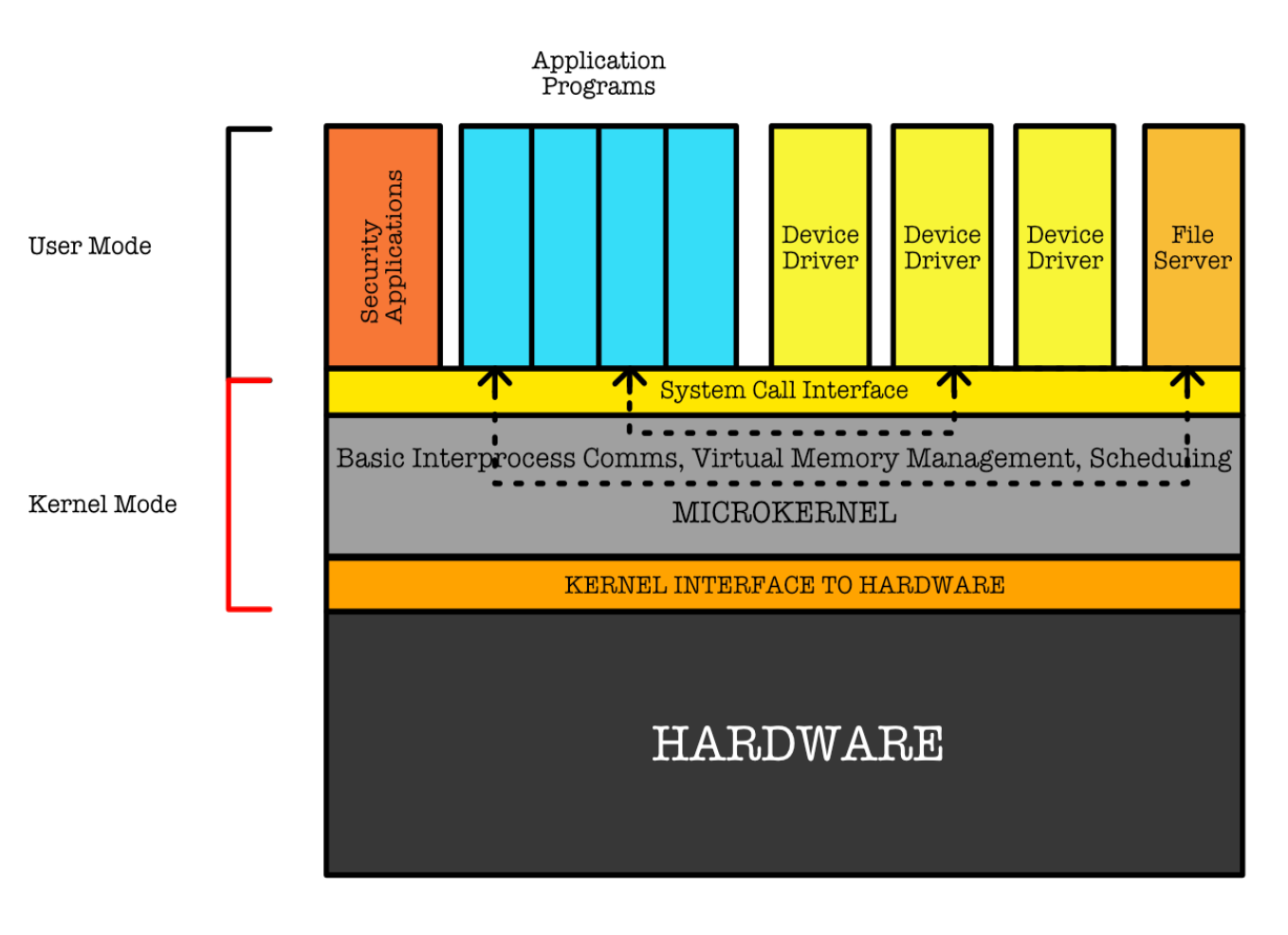

Microkernel

A microkernel is a very small kernel that provides minimal process and memory management, in addition to a communication facility.

This method structures the operating system by removing all nonessential components from the kernel and implementing them as system and user-level programs. The result is a smaller kernel that does only tasks pertaining to:

- Inter-Process Communication,

- Memory Management,

- Scheduling

For instance, if a user program wishes to access a file, it must interact with the file server.

- The client program and service never interact directly.

- Rather, they communicate indirectly by exchanging messages with the microkernel as illustrated below:

Pros: extending the operating system easier. All new services are added to user space and consequently do not require modification of the kernel.

Cons: suffer in performance increased system-function overhead due to frequent requirement in performing context switch.

Example: Mach, Windows NT (first release was a microkernel).

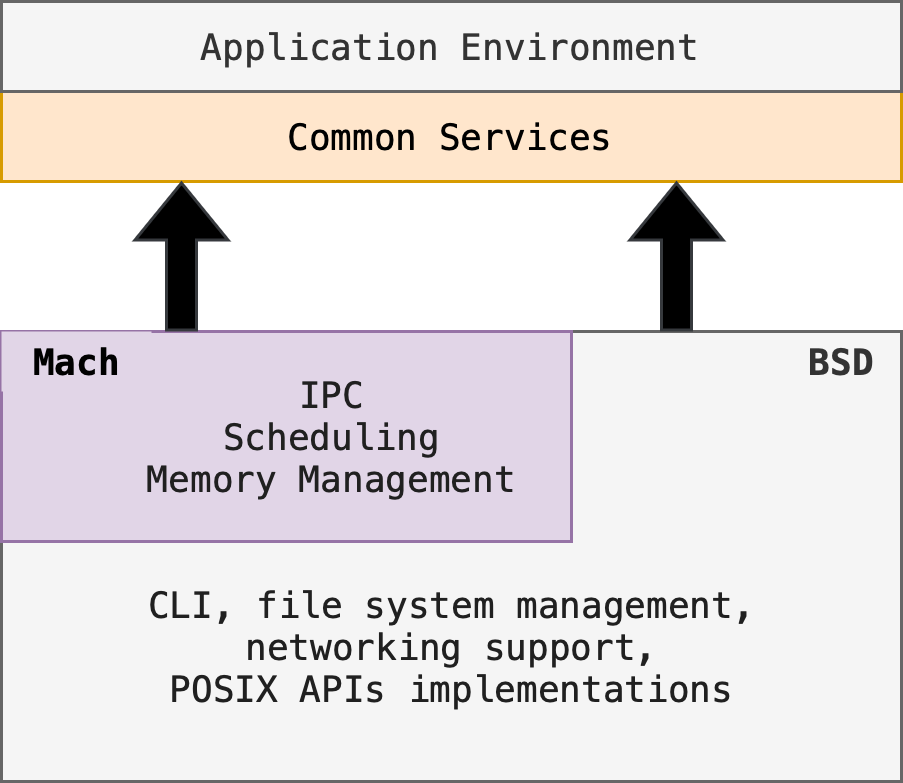

Hybrid Approach

Hybrid kernels attempt to combine between microkernel and monolithic kernel aspects and benefits.

Example: macOS is partly based on microkernel + monolithic approach (image taken from SGG):

- Mach provides: IPC, scheduling, memory management

- BSD provides: CLI, file system management, networking support, POSIX API implementations

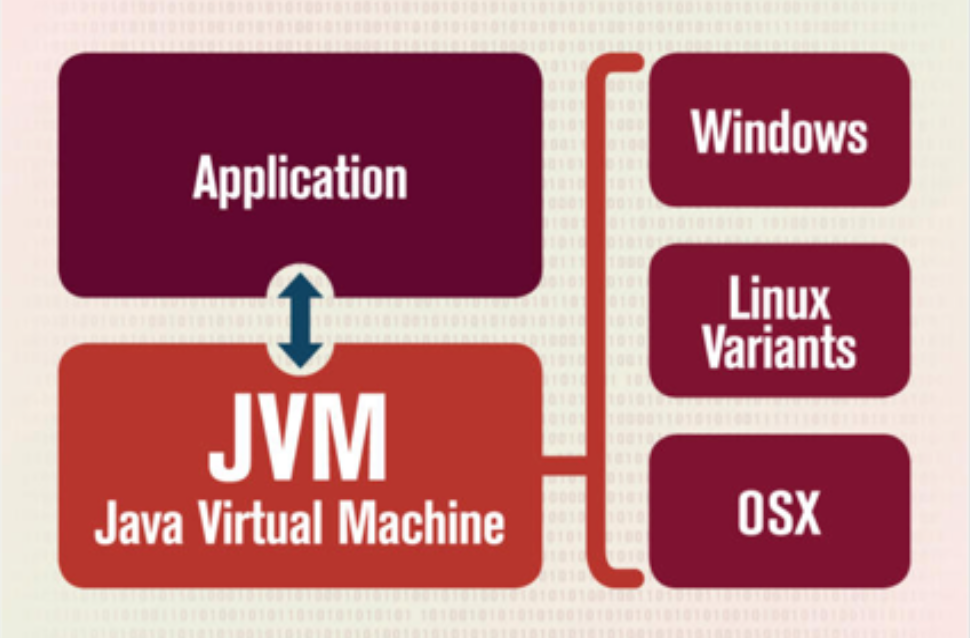

Java Operating System (JX)

The JX OS is written almost entirely in Java. Such a system, known as a language-based extensible system, and runs in a single address space (no virtualisation, no MMU), as such it will face difficulties in maintaining memory protection that is usually supported by hardwares in typical OS.

Language-based systems instead rely on type-safety4 features of the language. As a result, language-based systems are desirable on small hardware devices, which may lack hardware features that provide memory protection. Since Java is a type-safe language, JX is able to provide isolation between running Java applications without hardware memory protection.

This is called language based protection, where system calls and IPC in JX does not require an address-space switch. In short, JX runs in a single address space.

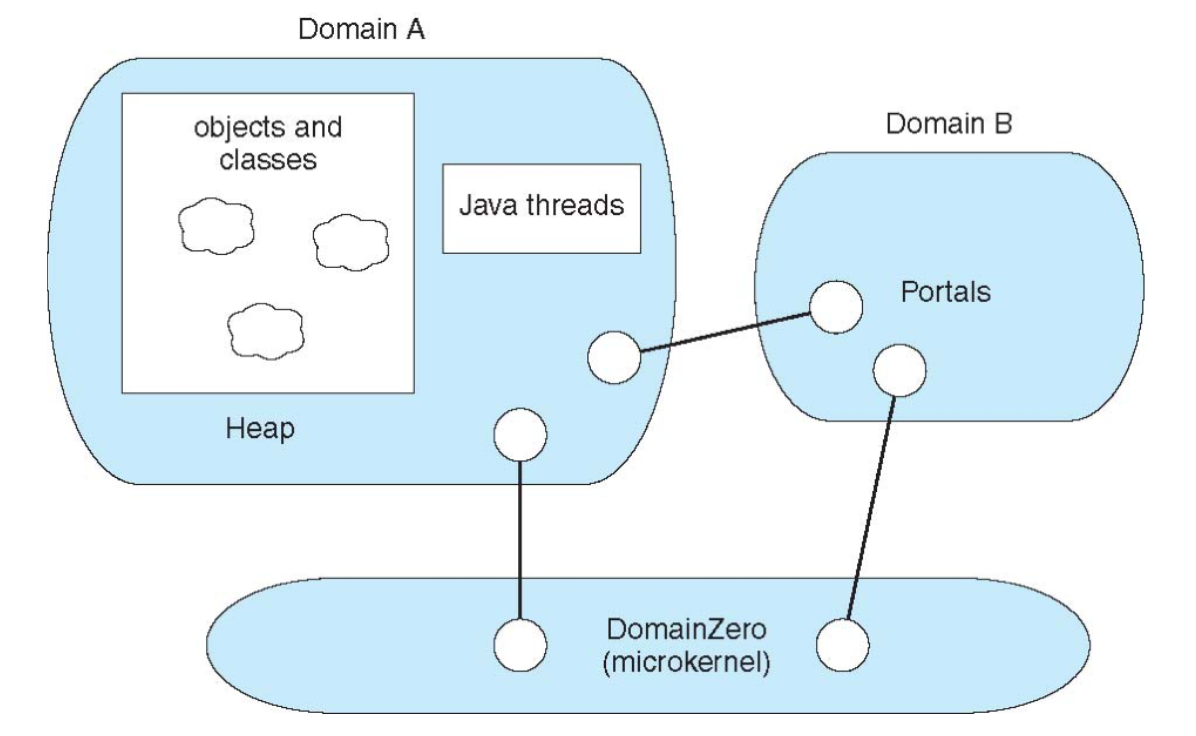

The architecture of the JX system is illustrated below (simplified representation5):

-

JX organizes its system according to domains.

- Each domain represents an independent JVM (Java Virtual Machine):

- JVM is an abstract virtual machine that can run on any OS

- There’s one instance of JVM per Java application

- JVM provides portable execution environment for Java-based apps

- It maintains a heap used for allocating memory during object creation and threads within itself, as well as for garbage collection.

- Domain zero is a microkernel responsible for low-level details, such as system initialization and saving and restoring the state of the CPU.

- Domain zero is written in C and assembly language; all other domains are written entirely in Java.

- Communication between domains occurs through a specific mechanism called portals

- Protection within and between domains relies on the type safety of the Java language.

- However, since domain zero is not written in Java, it must be considered trusted (built by trusted sources)

Garbage collection (GC) is a form of automatic memory management that helps in reclaiming memory occupied by objects that are no longer in use by a program. This process is crucial in preventing memory leaks and optimizing the use of available memory, ensuring that a program runs efficiently.

For more information, you can consult the appendix.

Summary

This section explains the architecture of modern operating systems, exploring their components and the critical roles they play in system functionality. It highlights the distinction between system and application programs, with a focus on how system programs interact with the kernel through system calls. Various OS structures such as monolithic, layered, microkernel, and hybrid models are discussed to illustrate their design and implementation complexities.

Key learning points include:

- Design Approaches: Comparison of monolithic, layered, microkernel, and hybrid OS structures, each with unique benefits and trade-offs in terms of efficiency, flexibility, and complexity.

- System Programs and User Programs: Exploration of their roles, differences, and interactions within the OS.

- Policy and Mechanism Separation: The importance of distinguishing and separating the ‘what’ (policy) from the ‘how’ (mechanism) to ensure system flexibility and ease of maintenance.

For a comprehensive understanding, further details can be explored in the original notes here.

The figure below shows the summary of various OS structures.

For layered architecture, note that the only difference with hybrid and microkernel structure is that programs at level N relies ONLY on services provided by programs at one level below it.

Appendix

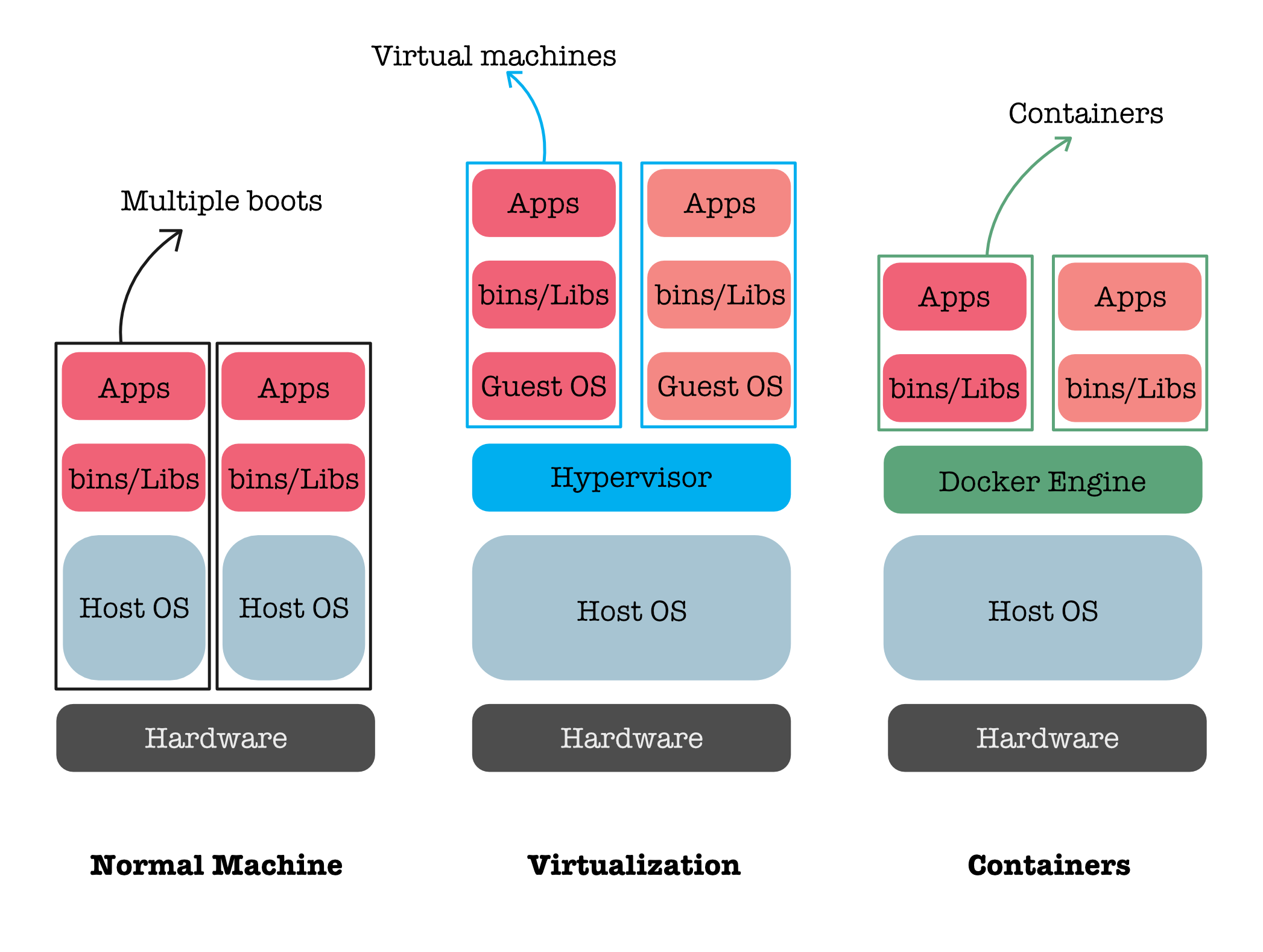

If you’d like to expand your knowledge beyond regular OS, you may have further read about virtualization and containerization.

Virtualisation

OS Virtualization refers to the creation of a virtual environment where an operating system can run on top of another through the use of software. This allows multiple operating systems to run on a single physical machine, each isolated from the others, enabling efficient resource utilization and flexibility in deploying different software or operating system environments.

A Hypervisor is the software that makes OS virtualization possible. It sits between the hardware and the operating systems and manages the distribution of hardware resources to the various virtual environments (often called virtual machines or VMs). There are two main types of hypervisors:

-

Type 1 Hypervisors: Also known as bare-metal hypervisors, these run directly on the host’s hardware to control the hardware and to manage guest operating systems. For example, VMware ESXi, Microsoft Hyper-V, and Xen are Type 1 hypervisors.

-

Type 2 Hypervisors: Also known as hosted hypervisors, these run on a conventional operating system just as other computer programs do. The host operating system provides device support and manages the physical hardware. Examples include VMware Workstation and Oracle VirtualBox.

Both types of hypervisors help in providing the virtualization capabilities that allow multiple OS instances to run simultaneously on the same machine, each thinking it has its own set of hardware resources.

Containerization

Containers allow a developer to package up an application with all of the parts it needs, such as libraries and other dependencies, and ship it all out as one package. Containers are not the same as Virtual Machines, and are generally faster to use. You can read more about the differences between the two here.

Note: “Host OS” in the picture above assumes that it is UNIX-based POSIX compliant OS. If you run Docker on Windows/Mac, it will download a Hypervisor + Guest Linux too before you can run the Docker Engine.

Example of software applications that support containerisation: Docker.

Java OS Details

In Java, the management of processes is largely abstracted from the developer by the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). Here’s a breakdown of how process management works in Java:

- Threads and Processes:

- Java does not manage processes directly in the same way as an operating system. Instead, Java applications typically run as a single process within the JVM.

- Within this process, Java can manage multiple threads. Threads in Java are managed by the JVM and can be either user threads or daemon threads.

- Java Threads:

- Java provides a robust threading model that allows for concurrent execution of code. This is done using the

java.lang.Threadclass and thejava.util.concurrentpackage. - Java threads are mapped to native operating system threads. This means that the underlying OS is responsible for scheduling and executing these threads.

- Java provides a robust threading model that allows for concurrent execution of code. This is done using the

- JVM and the OS Kernel:

- The JVM relies on the underlying OS kernel for fundamental process and thread management tasks. This includes scheduling, context switching, and inter-process communication.

- When you create and manage threads in a Java application, the JVM interfaces with the OS to handle these threads. The OS kernel’s scheduler is responsible for allocating CPU time to each thread based on its scheduling algorithm (e.g., round-robin, priority-based).

- Java’s Concurrency Utilities:

- Java provides a high-level API for managing concurrency through the

java.util.concurrentpackage. This includes classes likeExecutorService,Future, andSemaphorethat facilitate advanced thread management and synchronization. - These utilities abstract away many of the complexities of thread management and synchronization, allowing developers to focus on higher-level concurrency tasks.

- Java provides a high-level API for managing concurrency through the

- Garbage Collection:

- Another aspect of process management in Java is garbage collection. The JVM includes garbage collectors that automatically reclaim memory occupied by objects that are no longer in use.

- Garbage collection runs in its own threads and can impact the performance of a Java application. The JVM provides various garbage collection algorithms (e.g., Serial, Parallel, G1) that can be tuned based on the application’s requirements.

- Process Management:

- While Java itself doesn’t manage OS-level processes, it can interact with them using the

java.lang.Processandjava.lang.ProcessBuilderclasses. These classes allow Java applications to start and manage external processes. - Through these classes, a Java application can execute system commands, read and write to the standard input/output streams of the processes, and wait for them to complete.

- While Java itself doesn’t manage OS-level processes, it can interact with them using the

In summary, Java does not have its own scheduler for processes. Instead, it relies on the underlying OS kernel for basic process and thread management. Java provides a high-level abstraction over threads and concurrency, making it easier for developers to write concurrent programs without dealing with the low-level details of process management handled by the OS.

-

ttyitself is a command in Unix and Unix-like operating systems to print the file name of the terminal connected to standard input. If you open multiple terminal windows in your UNIX-based system and typettyon each of them, you will be returned with different ids. You may use write to communicate across terminal windows ↩ -

Early operating systems were written in assembly language. Now, although some operating systems are still written in assembly language, most are written in a higher-level language such as C or an even higher-level language such as C++. Actually, an operating system can be written in more than one language: (1) The lowest levels of the kernel might be assembly language, and then (2) higher-level routines might be in C, and finally (3) system programs might be in C or C++, in interpreted scripting languages like PERL or Python, or in shell scripts. In fact, a given Linux distribution probably includes programs written in all of those languages. ↩

-

Figure taken from Wikipedia ↩

-

The Java language is designed to enforce type safety. This means that programs are prevented from accessing memory in inappropriate ways. Every section of memory is part of some Java object that belongs to some class. For example, a calendar-management applet might use classes like Date, Appointment, Alarm, and GroupCalendar. Each class defines both a set of objects and operations to be performed on the objects of that class (explanation taken from Securing Java (ISBN: 047131952X), section 10) ↩

-

Image taken from https://webmobtuts.com/news-events/what-is-the-jvm-introducing-the-java-virtual-machine/ ↩

50.005 CSE

50.005 CSE