- Interprocess Communication

- POSIX Shared Memory

- Message Passing

- Message Passing vs Shared Memory

- Summary

- Appendix

50.005 Computer System Engineering

Information Systems Technology and Design

Singapore University of Technology and Design

Natalie Agus (Summer 2025)

Interprocess Communication

Detailed Learning Objectives

- Explain Process Independence vs Cooperation

- Identify the default nature of processes as independent.

- Identify that certain scenarios require processes to communicate

- Identify how a cooperating process can affect or be affected by other processes.

- Identify the reasons for process cooperation: information sharing, speeding up computations, and modularity for protection and convenience.

- Explain Interprocess Communication (IPC)

- Explain the two main IPC mechanisms: Shared Memory and Message Passing.

- Conclude kernel’s role in supporting IPC mechanisms.

- Describe Shared Memory as IPC

- Point out how shared memory allows multiple processes to access the same memory segment.

- Experiment how shared memory is created, accessed, and managed without continuous kernel assistance thereafter.

- Describe Message Passing as IPC

- Experiment how message passing allows processes to communicate and synchronize without sharing the same address space.

- Explain the roles of sockets in message passing and the involvement of the kernel in this IPC method.

These objectives are structured to provide a comprehensive overview of how processes may interact within a computer system through cooperation and communication, emphasizing the importance of IPC mechanisms.

Processes that are concurrently executing in the CPU may either be independent processes or cooperating processes:

- By default, processes are independent and isolated from one another (runs on its own virtual machine)

- A process is cooperating if it can affect or be affected by the other processes executing in the system.

Processes need to cooperate due to the following possible reasons:

- Information sharing

- Speeding up computations

- Modularity (protect each segments) and convenience

Cooperating processes require Interprocess Communication (IPC) mechanisms – these mechanisms are provided by or supported by the kernel. There are two ways to perform IPC:

- Shared Memory

- Message Passing (e.g: sockets)

POSIX Shared Memory

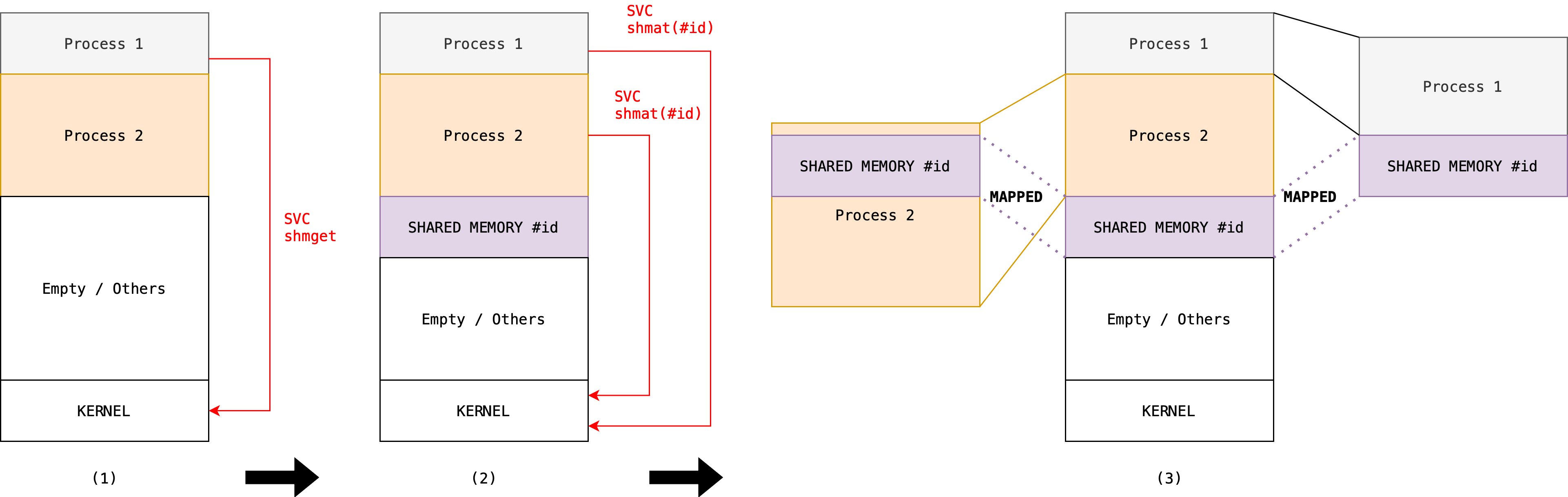

Shared memory is a region in the RAM that can be created and shared among multiple processes using system call.

- Kernel allocates and establishes a region of memory and return to the caller process.

- Once shared memory is established, all accesses are treated as routine user memory accesses for writing or reading to or from it, and no assistance from the kernel is required.

Procedure

This section is here to enhance your understanding. You can skip this if you want.

Both reader and writer get the shared memory identifier (an integer) using system call shmget. SHM_KEY is an integer that has to be unique, so any program can access what is inside the shared memory if they know the SHM_KEY. The Kernel will return the memory identifier associated with SHM_KEY if it is already created, or create it when it has yet to exist. The second argument: 1024, is the size (in bytes) of the shared memory.

int shmid = shmget(SHM_KEY, 1024, 0666 | IPC_CREAT);

Then, both reader and writer should attach the shared memory onto its address space (i.e: map the allocated segment in physical memory to the VM space of the calling process). You can type cast the return of shmat onto any data type you want. In essence, shmat returns an address of your address space that translates to the shared memory block1.

char *str = (char*) shmat(shmid, (void*)0, 0);

Afterwards, writer can write to the shared memory:

sprintf(str, "Hello world \n");

Reader can read from the shared memory:

printf("Data read from memory: %s\n", str);

The figure below illustrates the steps above:

Once both processes no longer need to communicate, they can detach the shared memory from their address space:

shmdt(str);

Finally, one of the processes can destroy it, typically the reader because it is the last process that uses it.

shmctl(shmid, IPC_RMID, NULL);

Of course one obvious issue that might happen here is that BOTH writer and reader are accessing the shared memory concurrently, therefore we will run into synchronisation problems whereby writer overwrites before reader finished reading or reader attempts to read an empty memory value before writer finished writing.

We will address such synchronisation problems in the next chapter.

Program: IPC without SVC?

Question

Will the value of

shared_intandshared_floatbe the same in the parent and child process?

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main(int argc, char const *argv[])

{

pid_t pid;

int shared_int = 10;

static float shared_float = 25.5;

pid = fork();

if (pid < 0)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Fork has failed. Exiting now");

return 1; // exit error

}

else if (pid == 0)

{

shared_int++;

printf("shared_int in child process: %d\n", shared_int);

shared_float = shared_float + 3;

printf("shared_float in child process: %f\n", shared_float);

}

else

{

printf("shared_int in parent process: %d\n", shared_int);

printf("shared_float in parent process: %f\n", shared_float);

wait(NULL);

printf("Child has exited.\n");

}

return 0;

}

Program: IPC with Shared Memory (unsync)

Parent and child processes can share the same segment, but we are faced with a synchronization problem, something called “race condition” (next week’s material).

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/ipc.h>

#include <sys/shm.h>

int main(int argc, char const *argv[])

{

pid_t pid;

int *ShmPTR;

int ShmID;

/**

This process asks for a shared memory of 4 bytes (size of 1 int) and attaches this

shared memory segment to its address space.

**/

ShmID = shmget(IPC_PRIVATE, 1 * sizeof(int), IPC_CREAT | 0666);

if (ShmID < 0)

{

printf("* shmget error (server) *\n");

exit(1);

}

/**

SHMAT attach the shared memory to the process

This code is called before fork() so both parent

and child processes have attached to this shared memory.

Pointer ShmPTR contains the address to the shared memory segment.

**/

ShmPTR = (int *)shmat(ShmID, NULL, 0);

if ((int)ShmPTR == -1)

{

printf("* shmat error (server) *\n");

exit(1);

}

printf("Parent process has created a shared memory segment.\n");

pid = fork();

if (pid < 0)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Fork has failed. Exiting now");

return 1; // exit error

}

else if (pid == 0)

{

*ShmPTR = *ShmPTR + 1; // dereference ShmPTR and increase its value

printf("shared_int in child process: %d\n", *ShmPTR);

}

else

{

printf("shared_int in parent process: %d\n", *ShmPTR); // race condition

wait(NULL); // move this above the print statement to see the change in ShmPTR value

printf("Child has exited.\n");

}

return 0;

}

Removing Shared Memory

In the code above, we didn’t detach and remove the shared memory, so it still persists in the system. Run the command ipcs -m to view it. To remove it, run the command ipcrm -m [mem_id]. To remove all shared memory, you can type the short script:

for n in `ipcs -b -m | grep ^m | awk '{ print $2; }'`; do ipcrm -m $n; done

Message Passing

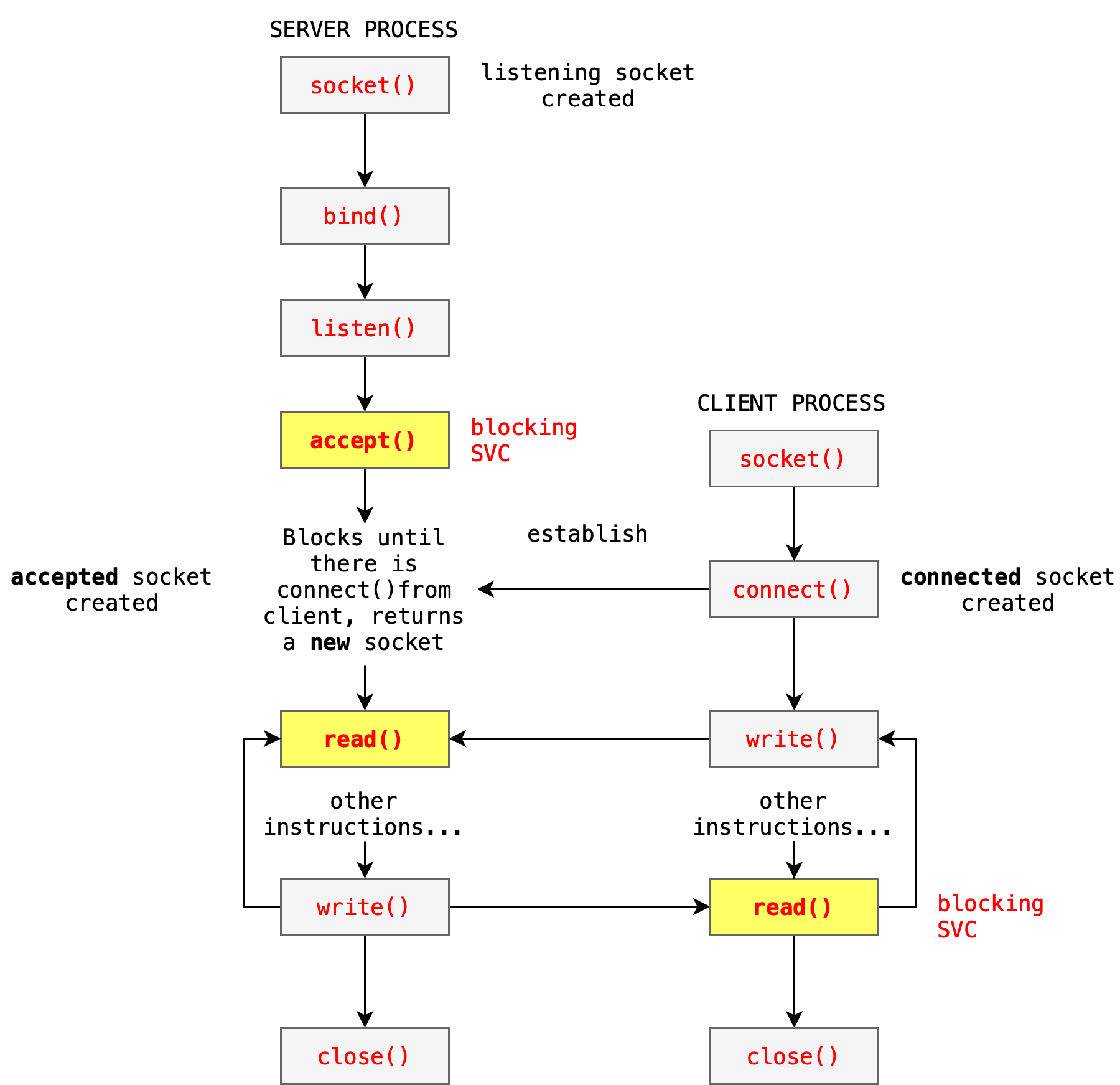

Message passing is a mechanism to allow processes to communicate and to synchronize their actions without sharing the same address space. Every message passed back and forth between writer and reader (server and client) through message passing must be done using kernel’s help.

Socket

Socket is one of message passing interfaces. It will be inaccurate to say that Socket is the only way to implement message passing.

A socket is one endpoint of a two-way communication link between two programs running on the network with the help of the kernel:

- Its identifier is a concatenation between an IP address, e.g: 127.0.0.1 for localhost and TCP (connection-oriented) or UDP (connectionless) port, e.g: 8080.

- We will learn more about UDP and TCP as network communication protocols in the later part of the semester.

- When concatenated together, they form a socket (more accurately, internet socket), e.g: 127.0.0.1:8080

- All socket connection between two communicating processes must be unique.

- Note: it is possible to “share” sockets through techniques called socket sharing. The details is out of the syllabus. You can view this appendix section if you’re interested.

TCP and UDP are different transport protocols. You will learn more about it in the next half of the semester, so don’t fret about it now. For now, this image sums it up.

For processes ran in the same machine (same computer), they communicate through a socket with IP localhost and a unique, unused port number. Processes can read()or send()data through the socket through system calls:

- For example, when P1 tries to

senda message (data) to P2 using socket, it has to copy the message from its own space to the kernel space first through the socket viawritesystem call. - Then, when P2 tries to

readfrom the socket, that message in the kernel space is copied again to P2’s space viareadsystem call.

The diagram below illustrates how socket works in general:

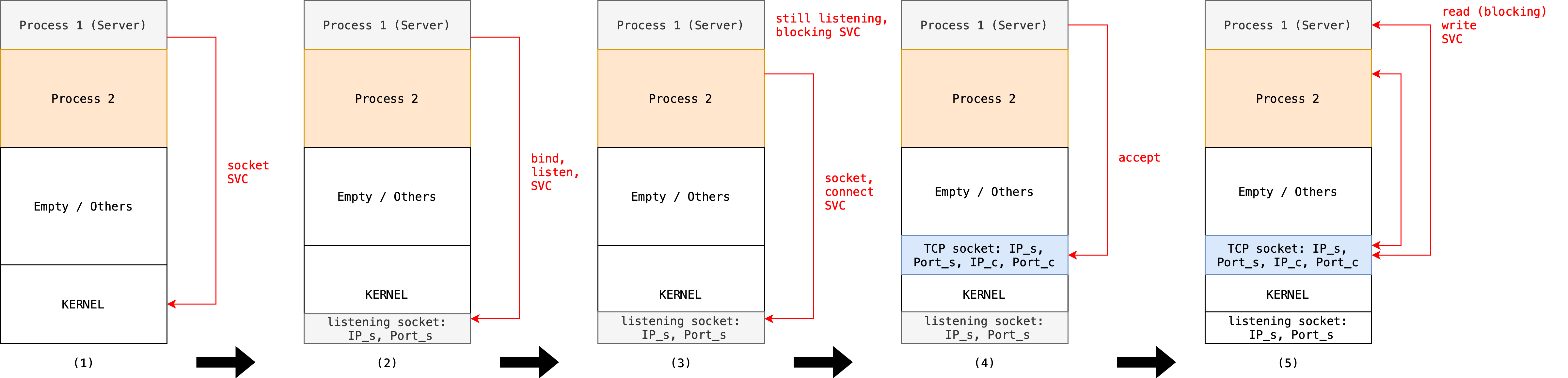

And below illustrates the evolution of the physical memory content when two processes communicate via socket:

- P1 (server) makes a system call to create a socket

- Kernel creates a listening socket and bind P1 to it

- P2 (client) makes a system call to create and connect to an existing socket (called a connected socket)

- Kernel creates a new communication socket between P1 and P2 (called an accepted socket)

- P1 and P2 can communicate via the established socket (accepted socket in P1’s side and connected socket in P2’s side) in step 4 using

writeandreadsystem calls

To summarize:

- Listening socket: Created by P1 and used to listen for incoming connections.

- Accepted socket: Created by the kernel when P1 accepts the connection from P2, used for communication.

- Connected socket: Created by P2 and used to establish a connection to the server and for communication.

Blocking recv/read

The recv operation is blocking by default. This means that if no data is available to be read from the socket, the operation will block the execution of the program. The calling program remains in a waiting state, effectively pausing its execution at that point, until data arrives on the socket. Once data is available on the socket (e.g., a packet is received from the network), the read operation will proceed.

Blocking send/write

The send operation also blocks when the socket’s send buffer is full. If the send buffer is full because the remote peer is not reading data fast enough, or there is high network congestion, the buffer cannot accept more data. In blocking mode, if the buffer is full, the send call will block the execution of the program. This means the function call will not return until there is sufficient space in the buffer to accommodate the data being sent.

During this blocking period, the program remains paused at the send call, waiting for the buffer to have enough space. This occurs when the remote peer reads some of the previously sent data, freeing up space in the buffer. Once the send buffer has enough space, the send() function proceeds to copy the data into the buffer.

Blocking recvs/reads and sends/writes on sockets provide a straightforward way to achieve automatic synchronization, managed by the kernel.

Non-blocking recv and send

Although these operations are blocking by default, we can set it such that they are non-blocking.

Non-blocking recv: In non-blocking mode, if no data is available to read, the recv() or read() function will return immediately with an error code (typically EWOULDBLOCK or EAGAIN).

Non-blocking send: If the buffer is full, the send() call returns immediately with a special error code (e.g., EWOULDBLOCK or EAGAIN), indicating that the operation could not be completed.

Program: IPC using Socket

You will have a hands-on experience with socket programming in Programming Assignment 2.

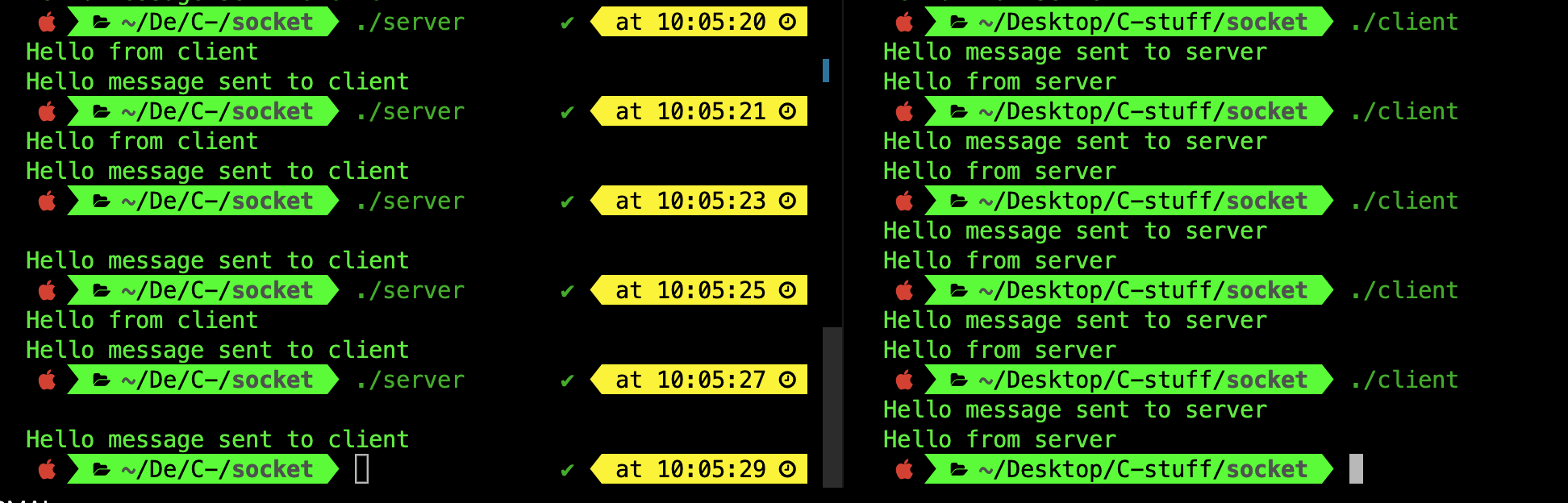

One process has to create a socket and listens for incoming connection. We call this process the server. After a listening socket is created, another process can connect to it. We call this process the client.

Server process has to be run first, followed by the client process. The code below implements both versions: blocking and non blocking read(). Try blocking version, then nonblocking.

Server program:

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h> /* Added for the nonblocking socket */

#define PORT 12345

int main(int argc, char const *argv[])

{

int server_fd, new_socket, valread;

int opt = 1;

struct sockaddr_in address;

int addrlen = sizeof(address);

char buffer[1024] = {0};

char *message = "Hello from server";

// Creating socket, and obtain the file descriptor

// Option:

// - SOCK_STREAM (TCP -- Week 11)

// - AF_INET (IPv4 Protocol -- Week 11)

if ((server_fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0)) == 0)

{

perror("socket failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Attaching socket to port 12345

if (setsockopt(server_fd, SOL_SOCKET, SO_REUSEPORT,

&opt, sizeof(opt)))

{

perror("setsockopt");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

address.sin_family = AF_INET;

address.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

address.sin_port = htons(PORT);

// Assign name to the socket

/**

When a socket is created with socket(2), it exists in a name

space (address family) but has no address assigned to it. bind()

assigns the address specified by addr to the socket referred to

by the file descriptor sockfd. addrlen specifies the size, in

bytes, of the address structure pointed to by addr.

Traditionally, this operation is called "assigning a name to a

socket".

**/

if (bind(server_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&address,

sizeof(address)) < 0)

{

perror("bind failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// server listens for new connection (blocking system call)

if (listen(server_fd, 3) < 0)

{

perror("listen");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// accept incoming connection, creating a 1-to-1 socket connection with this client

if ((new_socket = accept(server_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&address,

(socklen_t *)&addrlen)) < 0)

{

perror("accept");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Choose between blocking and nonblocking read

// Blocking read

valread = read(new_socket, buffer, 1024);

// Nonblocking read

// fcntl(new_socket, F_SETFL, O_NONBLOCK); /* Change the socket into non-blocking state */

// valread = recv(new_socket, buffer, 1024, 0);

printf("%s\n", buffer);

send(new_socket, message, strlen(message), 0);

printf("Hello message sent to client\n");

return 0;

}

Client program:

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h> /* Added for the nonblocking socket */

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#define PORT 12345

int main(int argc, char const *argv[])

{

struct sockaddr_in address;

int sock = 0, valread;

struct sockaddr_in serv_addr;

char *message = "Hello from client";

char buffer[1024] = {0};

// create a socket

if ((sock = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0)) < 0)

{

printf("\n Socket creation error \n");

return -1;

}

// fill block of memory 'serv_addr' with 0

memset(&serv_addr, '0', sizeof(serv_addr));

// setup server address

serv_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

serv_addr.sin_port = htons(PORT);

// Convert IPv4 addresses from text to binary form and store it at serv_addr.sin_addr

if (inet_pton(AF_INET, "127.0.0.1", &serv_addr.sin_addr) <= 0)

{

printf("\nInvalid address/ Address not supported \n");

return -1;

}

// connect to the socket with defined serv_addr setting

if (connect(sock, (struct sockaddr *)&serv_addr, sizeof(serv_addr)) < 0)

{

printf("\nConnection Failed \n");

return -1;

}

// send some data over

send(sock, message, strlen(message), 0);

printf("Hello message sent to server\n");

// read from server back

valread = read(sock, buffer, 1024);

printf("%s\n", buffer);

return 0;

}

When you recompile the server to implement valread via nonblocking manner, you might observe inconsistent behavior when you spawn server and client multiple times:

This is because server will not wait for any messages from the client before returning from recv, and so we can only observe the message Hello from client to be printed out before Hello message sent to client if client process is scheduled before server process.

You can exaggerate this behavior by adding a sleep(1); instruction in the client code right after it’s established connection to the server but before it sends any message to the server.

Both recv() and read() can be used for reading data from a socket, but recv() is typically preferred in socket programming due to its additional options

Message Queue

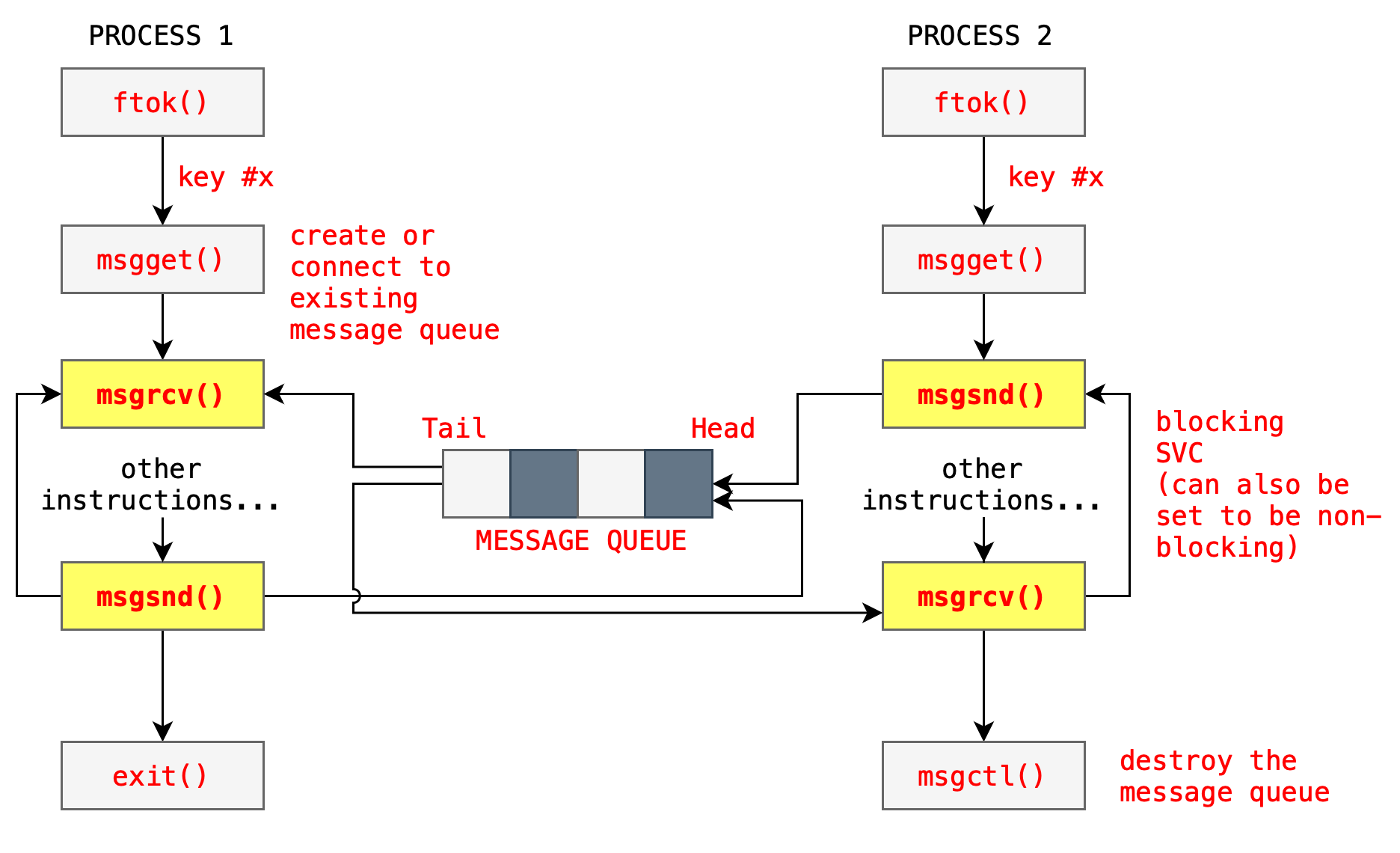

Message Queue is just another interface for message passing (another example being socket as shown in the previous section). It uses system call ftok, msgget, msgsnd, msgrcv each time data has to be passed between the processes. msgrcv and msgsnd can be made blocking or non blocking depending on the setup. Example applications that utilises message queue are: RabbitMQ, Apache Kafka, and Amazon SQS.

The figure below illustrates the general idea of Message Queue. The queue data structure is maintain by the Kernel, and processes may write into the queue at any time. If there are more than 1 writer and 1 reader at any instant, careful planning has to be made to ensure that the right message is obtained by the right process.

Writer program:

// C Program for Message Queue (Writer Process)

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/ipc.h>

#include <sys/msg.h>

#define MAX 10

// structure for message queue

struct mesg_buffer

{

long mesg_type;

char mesg_text[100];

} message;

int main()

{

key_t key;

int msgid;

// ftok to generate unique key

// key_t ftok (const char *pathname, int proj_id);

// pathname to existing file, proj_id: any number

// ftok uses the pathname and proj_id to create a unique value

// that can be used by different process to attach to shared memory

// or message queue or any other mechanisms.

key = ftok("~/somefile", 128);

// msgget creates a message queue

// and returns identifier

msgid = msgget(key, 0666 | IPC_CREAT);

message.mesg_type = 1;

printf("Write Data : ");

fgets(message.mesg_text,MAX,stdin);

// msgsnd to send message

msgsnd(msgid, &message, sizeof(message), 0);

// display the message

printf("Data send is : %s \n", message.mesg_text);

return 0;

}

Reader program:

// C Program for Message Queue (Reader Process)

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/ipc.h>

#include <sys/msg.h>

// structure for message queue

struct mesg_buffer

{

long mesg_type;

char mesg_text[100];

} message;

int main()

{

key_t key;

int msgid;

// ftok to generate unique key

key = ftok("~/somefile", 128);

// msgget creates a message queue

// and returns identifier

msgid = msgget(key, 0666 | IPC_CREAT);

// msgrcv to receive message

msgrcv(msgid, &message, sizeof(message), 1, 0);

// display the message

printf("Data Received is : %s \n",

message.mesg_text);

// to destroy the message queue

msgctl(msgid, IPC_RMID, NULL);

return 0;

}

Message Queue vs Socket

Both message queues and sockets can handle messages in a first-in, first-out (FIFO) order, but the key differences lie in how they manage this order and the context in which they operate. Message queues offer decoupling, persistence, and asynchronous processing, making them ideal for distributed systems requiring reliable communication. Sockets provide real-time, direct communication, making them suitable for applications needing immediate data transfer and low latency.

The analogy is as follows: imagine two people trying to talk. Socket is like a phone call: both people must pick up the phone and talk in real time. Both must be connected at the same time. The kernel passes bytes through a pipe, not full messages. Message queue is like a mailbox: each person can write a note and drop it in a box. Both don’t need to be available at the same time, and the box acts like a queue. Kernel stores, orders, and delivers each message (as a whole, not byte by byte). Each msgsnd() sends one complete message, and each msgrcv() receives exactly one full message.

Message Queue

Order Handling:

- FIFO: Message queues typically ensure FIFO order as a core feature, meaning messages are dequeued in the same order they were enqueued.

- Guarantees: Many message queue implementations provide strong guarantees about message order and delivery, including handling retries and ensuring no message is lost even in the event of a crash or network failure.

Operational Context:

- Asynchronous Processing: Producers and consumers operate asynchronously, which means the producer can continue to send messages without waiting for the consumer to process them.

- Persistence: Messages can be stored persistently in the queue until they are processed, ensuring reliability and durability.

- Buffering and Throttling: Message queues can buffer a large number of messages and throttle processing based on consumer availability and load, providing a way to smooth out spikes in traffic. This is typically way larger than what sockets can handle.

Socket

Order Handling:

- FIFO: Sockets, particularly with TCP (Transmission Control Protocol), ensure that data is received in the same order it was sent. TCP manages this by sequencing packets and ensuring ordered delivery.

- Real-time: The FIFO nature of sockets applies to real-time, continuous data streams, where the order of data packets is maintained strictly in the sequence they were sent.

Operational Context:

- Direct Communication: Sockets require a direct, live connection between the sender and receiver. Both ends must be active and connected for data to be transmitted.

- No Persistence: Sockets do not inherently provide message persistence. If the connection drops or the receiver is not ready to process data, the data can be lost unless additional mechanisms are implemented.

- Immediate Processing: Data sent over sockets is typically processed immediately upon receipt. This real-time processing is crucial for applications requiring low-latency communication.

Detailed Differences

- Connection Requirement:

- Message Queue: No need for a continuous connection between sender and receiver. Messages are stored until the receiver is ready to process them.

- Socket: Requires an active connection between sender and receiver. If the connection drops, communication is interrupted.

- Decoupling:

- Message Queue: Decouples the producer and consumer, allowing them to operate independently and at different rates.

- Socket: Tight coupling, requiring both endpoints to be ready for communication simultaneously.

- Persistence and Reliability:

- Message Queue: Provides mechanisms for persistence and reliability, ensuring messages are not lost even in failure scenarios.

- Socket: Relies on the connection being active and does not inherently provide persistence. Data may be lost if the connection fails.

- Use Case Suitability:

- Message Queue: Suitable for asynchronous, decoupled communication, where reliability and order are critical over time.

- Socket: Suitable for real-time, bidirectional communication, where immediate data transfer and low latency are essential.

Number of processes involved

Message queues can involve multiple producers and consumers, allowing many processes to send and receive messages asynchronously and independently. In contrast, sockets typically involve just two processes, one on each end of the connection, enabling live, direct, point-to-point communication.

Message Passing vs Shared Memory

Message Passing and Shared Memory both facilitate interprocess communication (IPC), but they do so in different ways with distinct advantages and challenges:

-

Number of system calls made:

-

Message Passing, e.g: via socket requires system calls for each message passed through

send()andreceive()but it is much quicker compared to shared memory to use if only small messages are exchanged. -

Shared memory requires costly system calls (

shmgetandshmat) in the beginning to create the memory segment (this is very costly, depending on the size, pagetable update is required during attaching), but not afterwards when processes are using them.

-

-

Number of procs using:

-

Message passing is one-to-one: only between two processes

-

Shared memory can be shared between many processes.

-

-

Usage comparison:

-

Message passing is useful for sending smaller amounts of data between two processes, but if large data is exchanged then it will suffer from system call overhead.

-

Shared memory is costly if only small amounts of data are exchanged. Useful for large and frequent data exchange.

-

-

Synchronization mechanism:

-

Message passing does not require any synchronisation mechanism (because the Kernel will synchronise the two). It will block if required (but can be set to not be blocking too, i.e: block/not block if there’s no message to read but one process requests to read)

-

Shared memory requires additional synchronisation to prevent race-condition issues (burden on the developer). There’s no blocking support. It also has to be freed after they are no longer needed, otherwise will persist in the system until its turned off (check for existing shared memories using

ipcsin terminal)

-

Choosing between them typically depends on the specific needs for efficiency, safety, and the system architecture in which the processes operate.

Summary

This chapter explores the vital role of Interprocess Communication (IPC) in allowing processes to coordinate and manage shared resources efficiently. It details two primary IPC mechanisms: Shared Memory and Message Passing. Shared Memory allows processes to access and manipulate the same memory segments, facilitating quick and efficient data exchange. Message Passing, including techniques like sockets and message queues, enables processes to communicate without direct memory sharing, ensuring data encapsulation and process safety.

Key learning points include:

- Shared Memory and Message Passing: Outlines the two main IPC mechanisms, explaining how shared memory allows direct access to a common memory space, whereas message passing involves sending messages through a system-managed channel.

- Synchronization and Race Conditions: Discusses the need for synchronization to avoid race conditions, particularly when using shared memory.

- Practical Applications: Provides examples of IPC in real-world applications, such as how browsers like Google Chrome use separate processes for different tabs to enhance stability and security.

Appendix

Application: Chrome Browser Multi-process Architecture

Websites contain multiple active contents: Javascript, Flash, HTML etc to provide a rich and dynamic web browsing experience. You may open several tabs and load different websites at the same time. However, some web applications contain bugs, and may cause the entire browser to crash if the entire Chrome browser is just one single huge process.

Google Chrome’s web browser was designed to address this issue by creating separate processes to provide isolation:

- The Browser process (manages user interface of the browser (not website), disk and network I/O); only one browser process is created when Chrome is just opened

- The Renderer processes to render web pages: a new renderer process is created for each website opened in a new tab

- The Plug-In processes for each type of Plug-In

All processes created by Chrome have to communicate with one another depending on the application. The advantage of such multi process architecture is that:

- Each website runs in isolation from one another: if one website crashes, only its renderer crashes and the other processes are unharmed.

- Renderer will also be unable to access the disk and network I/O directly (runs in sandbox: limited access) thus reducing the possibility of security exploits.

- Each process can be scheduled independently, providing concurency and responsiveness.

Socket Sharing

While a single socket connection typically facilitates communication between two processes, it is possible to use sockets to enable communication among multiple processes through techniques such as socket sharing, multiple connections, and broadcasting. Let’s get into further details about these concepts and see how they can be used effectively for inter-process communication (IPC).

Communication Between Two Processes

A typical socket communication scenario involves two processes:

- Client-Server Model:

- Server Process: Creates a socket, binds it to an address (IP and port), listens for incoming connections, and accepts a connection from a client.

- Client Process: Creates a socket and connects to the server’s address.

Communication Among Multiple Processes

To facilitate communication among multiple processes, we can use several strategies:

- Multiple Connections:

- A server can handle multiple clients by accepting multiple connections. Each client communicates with the server through its own socket connection.

- The server can use techniques like multi-threading or asynchronous I/O to handle multiple connections simultaneously.

- Socket Sharing:

- A socket can be shared among multiple processes using techniques like

fork()in UNIX-based systems, where a parent process creates a socket and then forks child processes that inherit the socket. - This allows child processes to communicate with the same socket, enabling communication among them.

- A socket can be shared among multiple processes using techniques like

- Broadcast and Multicast:

- For scenarios where messages need to be sent to multiple recipients, broadcasting (sending to all clients) or multicasting (sending to a group of clients) can be used.

- This is more common in networked environments rather than local IPC with UNIX domain sockets.

Example: Multiple Client Connections to a Server

Here’s an example illustrating how a server can handle multiple client connections using UNIX domain sockets. The server will accept connections from multiple clients and echo back any message it receives.

Server Code (Python):

import socket

import os

import threading

SOCKET_PATH = "/tmp/my_socket"

def handle_client(client_socket):

while True:

data = client_socket.recv(1024)

if not data:

break

print(f"Received: {data.decode()}")

client_socket.sendall(data)

client_socket.close()

def main():

if os.path.exists(SOCKET_PATH):

os.remove(SOCKET_PATH)

server_socket = socket.socket(socket.AF_UNIX, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

server_socket.bind(SOCKET_PATH)

server_socket.listen(5)

print("Server listening...")

try:

while True:

client_socket, addr = server_socket.accept()

print("Accepted connection")

client_handler = threading.Thread(target=handle_client, args=(client_socket,))

client_handler.start()

finally:

server_socket.close()

os.remove(SOCKET_PATH)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Client Code (Python):

import socket

SOCKET_PATH = "/tmp/my_socket"

message = "Hello, server!"

client_socket = socket.socket(socket.AF_UNIX, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

client_socket.connect(SOCKET_PATH)

client_socket.sendall(message.encode())

data = client_socket.recv(1024)

print(f"Echoed: {data.decode()}")

client_socket.close()

Conclusion

- Single Socket Connection: Generally used for communication between two processes.

- Multiple Connections: A server can handle multiple clients, each communicating via its own socket connection.

- Socket Sharing: Sockets can be inherited by child processes, allowing shared communication.

- Broadcast/Multicast: Useful for sending messages to multiple recipients in networked environments.

By using these techniques, you can extend the basic socket communication model to support IPC among multiple processes, enabling more complex and robust communication patterns.

-

Suppose process 1 and process 2 have successfully attached the shared memory segment.This attachment process causes this shared memory segment will be part of their address space, although the actual address could be different (i.e., the starting address of this shared memory segment in the address space of process 1 may be different from the starting address in the address space of process 2). ↩

50.005 CSE

50.005 CSE