- Synchronization in Java

- Java Condition Synchronization

- Reentrant Lock

- Summary

- Appendix

50.005 Computer System Engineering

Information Systems Technology and Design

Singapore University of Technology and Design

Natalie Agus (Summer 2025)

Synchronization in Java

Detailed Learning Objectives

- Examine Various Java Synchronization Mechanisms

- Identify the two basic synchronization idioms provided by Java: synchronized methods and synchronized statements.

- Explain the purpose and function of mutex locks associated with Java objects.

- Describe how mutex locks are acquired and released through synchronized methods and blocks.

- Explore the use of synchronized statements with specific named objects versus the anonymous ‘this’ instance.

- Show how to declare a synchronized method in Java and its implications.

- Examine Thread and Lock Management in Java

- Explain how Java maintains a queue to require object locks.

- Defend the distinction between the entry set and wait set of threads.

- Analyze the conditions under which a thread can acquire an object lock and become runnable.

- Explain Java Static and Reentrant Locks

- Discuss the concept and application of static synchronized methods and their association with class-level locks.

- Describe the differences between reentrant locks and non-reentrant locks.

- Explain the concept of reentrancy in locks and its practical application in Java programming.

- Analyze scenarios where reentrant locks are beneficial and situations where non-reentrant locks may cause problems.

- Implement basic Condition Synchronization in Java

- Examine Java’s mechanisms for condition synchronization using

wait()andnotify()methods.- Discuss the importance of managing thread states (sleep vs runnable) and conditions to prevent issues such as extraneous and spurious wakeups.

- Implement Fine-Grained Synchronization Using Condition Variables

- Show the use of named condition variables in conjunction with reentrant locks for more precise control over thread synchronization.

- Apply these concepts to practical coding scenarios to ensure correct synchronization and thread management.

These learning objectives are designed to help understand and apply Java’s synchronization mechanisms effectively in concurrent programming scenarios.

Java Object Mutex Lock

Java Monitor

In Java, every object acts as a monitor that provides built-in mutual exclusion and condition synchronization using

synchronized,wait(), andnotify(). A thread must hold the object’s monitor (viasynchronized) to callwait()ornotify(), which allows it to coordinate access and signal other threads waiting on shared conditions.

The Java programming language provides two basic synchronization idioms: synchronized methods and synchronized statements.

Each Java object has an associated binary lock:

- Lock is

acquiredby invoking a synchronized method/block - Lock is

releasedby exiting a synchronized method/block

With this lock, mutex is guaranteed for this object’s method; at most only one thread can be inside it at any time.

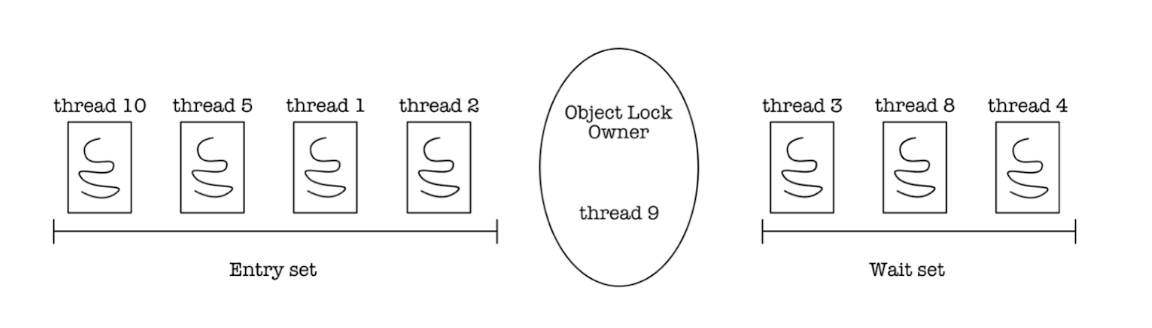

Threads waiting to acquire the object lock are waiting in the entry set, status is still blocked and not runnable until it acquires the lock. Once the thread acquires the lock, it becomes runnable.

The wait set is NOT equal to the entry set – it contains threads that are waiting for a certain condition.

This “certain” condition is not the lock.

These sets (entry and waiting) are per object, meaning each object instance only has one lock.

- Each object can have many synchronized methods.

- These methods share one lock.

Synchronised Method (Anonymous)

Below is an example of how you can declare a synchronized method in a class. The mutex lock is itself (this). The fact that we don’t use other objects as a lock is the reason why we call this the anonymous synchronisation object.

public synchronized returnType methodName(args)

{

// Critical section here

// ...

}

Synchronised Statement using Named Object

And below is a synchronized block based on a specific named object (not this instance).

Object mutexLock = new Object();

public returnType methodName(args)

{

synchronized(mutexLock)

{

// Critical section here

// ...

}

// Remainder section

}

You can also do a synchronized(this) if you’d like to use a synchronised statement anonymously.

Java Static Locks

It is also possible to declare static methods as synchronized. This is because, along with the locks that are associated with object instances, there is a single class lock associated with each class.

The class lock has its own queue sets. Thus, for a given class, there can be several object locks, one per object instance. However, there is only one (static) class lock.

Java Condition Synchronization

Similarly, Java allows for condition synchronization using wait() and notify() method, as well as its own condition variables.

Example: suppose a few threads are trying to execute the same method as follows, N threads are running this doWork function concurrently with argument id varying between 0 to N-1, i.e: 0 for thread 0, 1 for thread 1, and so on.

public synchronized void doWork(int id)

{

while (turn != id) // turn is a shared variable

{

try

{

wait();

}

catch (InterruptedException e)

{

}

}

// CRITICAL SECTION

// ...

turn = (turn + 1) % N;

notify();

}

In this example, the condition in question is that only thread whose id == turn can execute the CS.

When calling wait(), the lock for mutual exclusion must be held by the caller (same as the condition variable in the section above). That’s why the wait to the condition variable is made inside a synchronized method. If not, disaster might happen, for example the following execution sequence:

- At

t=0,- Thread Y check that

turn != id_y, and then Y is suspended by the asynchronous timer.

- Thread Y check that

- At

t=n,- Thread X resumes and increments the

turn. This causesturn == id_y. - Suppose X then calls

notify(), and then X is suspended

- Thread X resumes and increments the

- At

t=n+m,- Thread Y resumes execution and enters

wait().

- Thread Y resumes execution and enters

- However at this time, the value of

turnis ALREADY== id_y.

We can say that thread Y misses the notify() from X and might wait() forever. We need to make sure that between the check of turn and the call of wait(), no other thread can change the value of turn.

Since we must invoke wait() while holding a lock, it is important for wait() to release the object lock eventually (when the thread is waiting).

If you call another method to sleep such as Thread.yield() instead of wait(), then it will not release the lock while waiting.

This is dangerous as it will result in indefinite waiting or deadlock.

Upon return from wait(), the Java thread would have re-acquired the mutex lock automatically.

In summary,

-

When a thread calls the

wait()method, the following happens:- The thread releases the lock for the object.

- The state of the thread is set to blocked.

- The thread is placed in the wait set for the object.

-

When it calls

notify():- Picks an arbitrary thread T from the list of threads in the wait set

- Moves T from the wait set to the entry set

- The state of T will be changed from blocked to runnable, so it can be scheduled to reacquire the mutex lock

In Java, the wait() method is designed to be atomic in terms of releasing the monitor (lock) and entering the wait set. If you’re interested to find out why atomicity must be guaranteed, give this appendix section a read.

NotifyAll

Using only notify(), we are not completely free of another potential problem yet: notify() might not wake up the correct thread whose id == turn, and recall that turn is a shared variable.

We can solve the problem using another method notifyAll(): wakes up all threads in the wait set.

Waiting in a Loop

It is important to put the waiting of a condition variable in a while loop due to the possibility of:

- Spurious wakeup: a thread might get woken up even though no thread signalled the condition (

POSIXdoes this for performance reasons) - Extraneous wakeup: you woke up the correct amount of threads but some hasn’t been scheduled yet, so some other threads do the job first. For example:

- There are two jobs in a queue, and there’s two threads: thread A and B that got woken up.

- Thread A gets scheduled, and finishes the first job. It then finds the second job in the queue, and finishes it as well.

- Thread B finally gets scheduled and, upon finding the queue empty, crashes.

Reentrant Lock

A lock is re-entrant if it is safe to be acquired again by a caller that’s already holding the lock. You can create a ReentrantLock() object explicitly to allow reentrancy in your critical section.

Java synchronized methods and synchronized blocks with intrinsic lock are reentrant. Recall that every object has an intrinsic lock associated with it.

For example, a thread can safely recurse on blocks guarded by reentrant locks (sync methods, sync statement):

// Method 1

public synchronized void foo(int x) {

// some condition ...

foo(x-1); // recurse does not cause error

}

// Method 2

public void foo(int x) {

synchronized(this) { // note that 'this' is the lock. Otherwise, non-reentrant

// some condition ...

foo(x-1); // recurse does not cause error

}

}

// Method 3

Object obj1 = new Object();

synchronized(obj1){

System.out.println("Try out object ack 1");

synchronized(obj1){ // intrinsic lock is reentrant

System.out.println("Try out obj ack 2"); // will be printed

}

}

Reentrance Lockout

If you use a non-reentrant lock and recurse, or try to acquire the lock again, you will suffer from reentrance lockout. We demonstrate it with the custom lock below that’s not reentrant:

public class CustomLock{

private boolean isLocked = false;

public synchronized void lock() throws InterruptedException{

while(isLocked){

wait();

}

isLocked = true;

}

public synchronized void unlock(){

isLocked = false;

notify();

}

}

And the usage:

CustomLock lock = new CustomLock()

// Thread 1 code

public void doSomething(int argument){

lock.lock();

// recurse

doSomething(argument-1);

lock.unlock();

}

As a result, a thread that calls lock() for the first time will succeed, but the second call to lock() will be blocked since the variable isLocked == true.

Releasing Locks

One final point to note is that some implementations require you to release the lock N times after acquiring it N times.

You need to carefully consult the documentation to see if the locks are auto released or if you need to explicitly release a lock N times to allow others to successfully acquire it again.

If you’re interested to learn more about Java ReentrantLock release procedure, consult the appendix.

Fine-Grained Condition Synchronisation

If we want to perform fine grained condition synchronization, we can use Java’s named condition variables and a reentrant lock. Named condition variables are created explicitly by first creating a ReentrantLock(). The template is as follows:

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Condition;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock;

public class ConditionExample {

// STEP 1: Initialise lock

private final Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

// STEP 2: Initialise condition object

private final Condition condition = lock.newCondition();

// STEP 3: Initialise your condition

private boolean someCondition = false;

public void awaitCondition() throws InterruptedException {

lock.lock(); // Try acquire lock

// await() throws an exception, but place try outside of while (this is a good pattern)

try {

while (!someCondition) { // Put condition inside while loop as usual

condition.await(); // lock will be freed when yield (await)

}

// CRITICAL SECTION

// Proceed when someCondition is true

// ...

}

catch (InterruptedException e){

// do something in case there's exception

}

finally {

// finally block is always executed

lock.unlock();

}

}

public void signalCondition() {

lock.lock();

try {

// CRITICAL SECTION

// ....

// set custom condition to be true

someCondition = true;

// wake up the sleeping process

condition.signalAll(); // or condition.signal();

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

}

At first, we associate a condition variable with a lock: lock.newCondition(). This forces us to always hold a lock when a condition is being signaled or waited for.

We can modify the example above with N conditions similar to the example we had in the previous notes. Suppose a toy example whereby we have N threads running concurrently, and each thread can only progress if its id == turn. turn is a shared variable. We can use condition variables in Java as follows:

// Create arrays of condition

Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

ArrayList<Condition> condVars = new ArrayList<Condition>();

for(int i = 0; i<N; i++) condVars.add(lock.newCondition()); // create N conditions, one for each Thread

The Thread function is changed to incorporate a wait to each condVars[id]:

// the function

public void doWork(int id)

{

lock.lock();

try {

while (turn != id)

{

condVars[id].await();

}

// SAMPLE CRITICAL SECTION

// assume there's some work to be done here...

turn = (turn + 1) % N;

condVars[turn].signal();

}

catch (InterruptedException e){

// do something in case there's exception

}

finally{

lock.unlock();

}

}

The reason for placing the try-finally block outside the while loop is to ensure that the lock is always released, even if an exception occurs. You can read more about it in appendix. It is also worth to note that even though .signal or signalAll will throw an exception (unlike await), it is always a good pattern to place unlock() inside a finally block to ensure proper lock release as finally block is guaranteed to always be executed. We assume in general there are more parts of the critical section that might throw an exception.

Summary

This chapter discusses many synchronization techniques in Java which is essential for managing concurrent processes in programming. It explores mechanisms such as synchronized methods and blocks, static and reentrant locks, and condition synchronization using wait() and notify() methods. The guide covers practical aspects like mutex locks, thread management, and avoiding deadlocks, providing a comprehensive understanding of how Java handles synchronization to ensure thread safety and efficiency.

Key learning points include:

- Mutex Locks and Synchronization Blocks: Details on using synchronized methods and blocks to handle mutual exclusion within Java objects.

- Reentrant and Static Locks: Explores how reentrant locks allow threads to acquire the same lock multiple times safely, and the use of static locks for class-level synchronization.

- Condition Synchronization: Discusses the use of condition variables alongside locks to manage complex thread coordination and avoid issues like deadlocks and spurious wakeups.

To tie it up with the previous chapter, recall that there are a few solutions to the CS problem. The CS problem can be divided into two types:

- Mutual exclusion

- Condition synchronization

There are also a few solutions listed below.

- Software mutex algorithms provide mutex via busy-wait.

- Hardware synchronisation methods provide mutex via atomic instructions. Other software spinlocks and mutex algorithms can be derived using these special atomic assembly instructions

- Semaphores provide mutex using binary semaphores.

- Basic condition variables provide condition synchronization and are used along with a mutex lock.

- Java anonymous default synchronization object provides mutex using reentrant binary lock (

this), and provides condition synchronisation usingwait()andnotifyAll()ornotify() - Java named synchronization object provides mutex using named reentrant binary lock (

ReentrantLock()) and provides condition sync using condition variables andawait()/signal()

It is entirely up to you to figure out which one is suitable for your application.

Appendix

Ensuring Proper Lock Release

The reason for placing the try-finally block outside the while loop is to ensure that the lock is always released, even if an exception occurs. The lock must be released in a predictable manner, and putting the try-finally block inside the while loop can lead to scenarios where the lock might not be released properly if an exception is thrown.

Here’s a detailed explanation:

-

Ensuring Lock Release: The

finallyblock is used to guarantee that the lock is released, regardless of whether an exception occurs or not. If thetry-finallyblock is inside thewhileloop, and an exception occurs after the lock is acquired but before it is released, the lock might not be released properly. -

Exception Handling: Placing the

try-finallyblock outside thewhileloop allows you to handle exceptions in a controlled manner. If an exception occurs within thewhileloop, thefinallyblock will still execute, ensuring the lock is released.

Here is the correct pattern with try-finally outside the while loop:

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Condition;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock;

public class ConditionExample {

private final Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

private final Condition condition = lock.newCondition();

private boolean someCondition = false;

public void awaitCondition() throws InterruptedException {

lock.lock();

try {

while (!someCondition) {

condition.await();

}

// Proceed when someCondition is true

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

public void signalCondition() {

lock.lock();

try {

someCondition = true;

condition.signalAll(); // or condition.signal();

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

}

What happens if there’s no finally block?

Let’s try another case where there’s no finally block. The code will still compile and run, but there are potential problems:

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Condition;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock;

public class IncorrectConditionExample {

private final Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

private final Condition condition = lock.newCondition();

private boolean someCondition = false;

public void awaitCondition() throws InterruptedException {

lock.lock();

while (!someCondition) {

try {

condition.await();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

// Handle interruption

throw e; // Re-throw if you want the caller to handle the interruption

}

}

// CRITICAL SECTION

// Proceed when someCondition is true

lock.unlock();

}

public void signalCondition() {

lock.lock();

someCondition = true;

condition.signalAll(); // or condition.signal();

lock.unlock();

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

IncorrectConditionExample example = new IncorrectConditionExample();

// You can create threads to test awaitCondition and signalCondition here

}

}

Potential Problems:

- Lock Leak: If an exception is thrown inside the while loop or anywhere before lock.unlock(), the lock will never be released, causing a lock leak.

- Deadlock: When Lock Leak happens, other threads that need to acquire the same lock will get blocked indefinitely, leading to deadlock situations.

What Happens if try-finally is Inside the while Loop

If you put the try-finally inside the while loop, you risk not releasing the lock if an exception occurs outside the try block or before the lock is released:

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Condition;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock;

public class IncorrectConditionExample {

private final Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

private final Condition condition = lock.newCondition();

private boolean someCondition = false;

public void awaitCondition() throws InterruptedException {

lock.lock();

try {

while (!someCondition) {

try {

condition.await();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

// Handle interruption

throw e; // Re-throw if you want the caller to handle the interruption

} finally {

lock.unlock(); // This will release the lock prematurely

}

// At this point, the lock has been released, which can cause issues

lock.lock(); // Attempt to re-acquire the lock (not a good pattern)

}

// Proceed when someCondition is true

} finally {

lock.unlock(); // This will not match the number of lock acquisitions

}

}

public void signalCondition() {

lock.lock();

try {

someCondition = true;

condition.signalAll(); // or condition.signal();

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

IncorrectConditionExample example = new IncorrectConditionExample();

// You can create threads to test awaitCondition and signalCondition here

}

}

Issues with finally inside the while-loop:

- Premature Lock Release: The finally block inside the while loop releases the lock prematurely, which can lead to race conditions because other threads may acquire the lock and modify shared state unexpectedly.

- Re-acquiring the Lock: The pattern of re-acquiring the lock after the finally block is not safe and leads to incorrect lock management.

By placing the try-finally block outside the while loop, you ensure that the lock is always released correctly, maintaining the integrity of your concurrency control. This pattern helps prevent potential deadlocks and other concurrency issues.

Java ReentrantLock Release Procedure

When using a ReentrantLock in Java, you must release the lock the same number of times you acquired it. Each call to lock() must be matched with a corresponding call to unlock().

If you acquire the lock three times, you must call unlock() three times to fully release the lock. If an exception occurs after the three recursive calls, you need to ensure that all the unlock() calls are made to prevent a deadlock situation.

Here is an example to illustrate this:

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock;

public class ReentrantLockExample {

private final Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

public void recursiveMethod(int depth) {

lock.lock();

try {

System.out.println("Lock acquired, depth: " + depth);

if (depth > 0) {

recursiveMethod(depth - 1);

}

// Perform some operations

} catch (Exception e) {

// Handle exception

e.printStackTrace();

} finally {

System.out.println("Lock released, depth: " + depth);

lock.unlock();

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

ReentrantLockExample example = new ReentrantLockExample();

try {

example.recursiveMethod(3);

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

Explanation:

-

Recursive Lock Acquisition: The

recursiveMethodacquires the lock, prints the current depth, and then recursively calls itself withdepth - 1untildepthreaches 0. -

Lock Release: Each time the method returns from the recursive call, it reaches the

finallyblock and releases the lock by callingunlock(). This ensures that each acquisition of the lock is matched with a release, preventing deadlocks. -

Exception Handling: If an exception is thrown, it is caught in the

catchblock, but thefinallyblock will still execute, ensuring that the lock is always released properly.

What Happens if You Don’t Release the Lock Properly

If an exception occurs and you don’t release the lock properly, it can lead to a deadlock.

Here’s an example where improper handling could cause a problem:

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock;

public class FaultyReentrantLockExample {

private final Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

public void faultyRecursiveMethod(int depth) {

lock.lock();

try {

System.out.println("Lock acquired, depth: " + depth);

if (depth == 1) {

throw new RuntimeException("Exception at depth 1");

}

if (depth > 0) {

faultyRecursiveMethod(depth - 1);

}

// Perform some operations

} finally {

System.out.println("Lock released, depth: " + depth);

lock.unlock();

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

FaultyReentrantLockExample example = new FaultyReentrantLockExample();

try {

example.faultyRecursiveMethod(3);

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

In this example, if the exception is thrown at depth 1, the finally block ensures the lock is released at that depth, but because the method is called recursively, each previous depth must also ensure the lock is released. If any unlock is missed, it will lead to problems.

Ensuring Proper Lock Release in Case of Exceptions

To handle exceptions properly, ensure each level in the recursion releases the lock:

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock;

public class ProperReentrantLockExample {

private final Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

public void properRecursiveMethod(int depth) {

lock.lock();

try {

System.out.println("Lock acquired, depth: " + depth);

if (depth == 1) {

throw new RuntimeException("Exception at depth 1");

}

if (depth > 0) {

properRecursiveMethod(depth - 1);

}

// Perform some operations

} finally {

System.out.println("Lock released, depth: " + depth);

lock.unlock();

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

ProperReentrantLockExample example = new ProperReentrantLockExample();

try {

example.properRecursiveMethod(3);

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

By ensuring that the unlock() call is in the finally block, you make sure that the lock is always released, preventing potential deadlocks and ensuring the correct behavior of your code.

Java Atomic Wait

How wait() Works in Java

In Java, the wait() method is designed to be atomic in terms of releasing the monitor (lock) and entering the wait set. Here’s a closer look at the process:

- Atomic Release-and-Wait: When a thread calls

wait()on an object, it must hold the monitor (lock) of that object. Upon invocation ofwait(), Java does two things in an atomic operation:- Releases the Monitor: The thread releases the lock it holds on the object.

- Enters the Wait Set: Simultaneously, the thread is placed into the wait set associated with the object’s monitor.

- Guaranteed by JVM: This behavior is ensured by the Java Virtual Machine, which manages thread states and synchronization. The JVM guarantees that no other thread can intervene between these two operations. This means once a thread releases the lock through

wait(), it is already in the wait set before any other thread can acquire the lock and possibly callnotify()ornotifyAll().

JVM and Synchronization

- Synchronization Mechanisms: Java’s synchronization mechanisms are built around an intrinsic lock (or monitor) per object. The

wait(),notify(), andnotifyAll()methods must be used within a synchronized block or method, ensuring they are used correctly regarding locking. - Memory Model Compliance: Java’s memory model ensures that all actions in a thread before calling

wait()are visible to any thread that acquires the same lock afterwait()is called. This is important for maintaining consistency and visibility across threads.

Practical Implications

- No Missed Signals: If a thread calls

wait(), any subsequentnotify()ornotifyAll()calls will correctly find this thread in the wait set, assuming it’s still waiting when the notification is issued. There’s no risk of the thread being in a limbo state where it has released the lock but is not yet waiting. - Correct Handling of Concurrency: This atomic approach helps prevent common concurrency issues such as lost notifications, race conditions, or deadlocks related to incorrect lock handling or timing issues between threads.

Java’s design regarding the wait() and notify() mechanisms is crafted to avoid the exact kind of issues you’re concerned about, making Java a robust choice for developing multithreaded applications with complex synchronization needs.

50.005 CSE

50.005 CSE