- Which Pillar Fails?

- Just Enough Security?

- The Curious Ciphertext

- The Graph of Trust

- RSA in Action

- The Compromised Broadcast

- Replay Riches

- When Integrity Isn’t Enough

- Sign Before You See

- Timing the Leak

- Fast Enough?

- The Hijacked Port

- One Hash Too Many

- Padding Oracle

- Man in the Middle Manager

- Dual Use Danger

- Crypto Soup

- Patch the Handshake

- The Slippery Protocol

50.005 Computer System Engineering

Information Systems Technology and Design

Singapore University of Technology and Design

Natalie Agus (Summer 2025)

Network Security

The amount of questions for this topic is more than usual. Please explore them if you’re interested. Some questions are more difficult and tricky, and may not be applicable to 50.005 (more applicable to cybersecurity), but they are interesting and has been stripped out of many technicalities. Hence we select them to be in this list.

Which Pillar Fails?

Background: CIA

Cryptographic systems aim to ensure three main security goals:

- Confidentiality: Only the intended party can read the message.

- Integrity: The message wasn’t tampered with or altered in transit.

- Authentication: You’re communicating with the entity you think you are.

Sometimes, protocols break just one of these, and that’s all it takes.

Recognize that “secure” ≠ secure in all dimensions.

Scenario

For each situation below, identify which security goal is violated: Confidentiality, Integrity, or Authentication. More than one may apply.

- A message is encrypted using AES-CBC, but with a fixed IV reused every time.

- A system uses SHA-256 to check for tampering but doesn’t use any keys.

- A client receives a valid-looking TLS certificate from a server, but doesn’t check if it’s signed by a trusted CA.

- A device receives a message with a valid HMAC, but the shared key is used by many other clients.

- A report is encrypted and MACed, but the server doesn’t know who sent it or which client it came from.

- A software update is signed by the vendor but downloaded over HTTP.

- An IoT sensor encrypts and sends its data to the server. The key was hardcoded into the firmware and is now known.

1. Confidentiality: Fixed IVs in AES-CBC reveal message structure or repeated plaintexts.

2. Integrity: SHA-256 is not a keyed function; attackers can modify the message and recompute the hash.

3. Authentication: The client cannot verify the server’s identity without validating the certificate chain.

4. Authentication: If multiple clients share the same MAC key, the server can't tell who sent the message.

5. Authentication: The server has no idea which client sent the message, even if the message is secure.

6. Integrity + Confidentiality: Signature ensures authenticity, but HTTP allows tampering or eavesdropping in transit.

7. Confidentiality + Integrity: If the key is exposed, an attacker can decrypt or forge messages entirely.

Just Enough Security?

Security is not about applying all protections everywhere: it’s about choosing the right protections for the right risks. A messaging protocol might only need integrity. A broadcast alert might need only authentication. Encrypting everything doesn’t help if anyone can impersonate the sender.

In this problem, you’ll evaluate different CIA property combinations for real-world systems.

Scenario

For each of the systems below, assume the following protections are applied. Your task is to determine:

- Is this enough security for the purpose?

- If not, what’s missing and why?

| System | C | I | A | Is this enough? Why or why not? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. IoT broadcast alerts | ✗ | ✗ | ✔ | |

| 2. Login form sent over HTTPS | ✔ | ✔ | ✗ | |

| 3. Digital voting (encrypted vote storage) | ✔ | ✗ | ✔ | |

| 4. Anonymous whistleblower system | ✔ | ✔ | ✗ | |

| 5. API request with HMAC | ✗ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| 6. Software update signed with vendor key | ✗ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| 7. Messaging app using AES-CTR only | ✔ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 8. Medical record database with TLS | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

1. Enough: IoT alerts are public, so confidentiality and integrity aren't critical if we only care that alerts come from a known source. Authentication is sufficient.

2. Not enough: Without authentication, the server doesn’t know who is logging in. Anyone could intercept the form and replay it.

3. Not enough: Without integrity, vote data might be silently altered. Confidentiality hides the vote, but integrity ensures it wasn't changed.

4. Enough: Authentication is intentionally omitted. The system is designed to preserve anonymity while ensuring privacy and tamper-resistance.

5. Enough: This setup ensures both message authenticity and integrity using HMAC. Confidentiality may not be necessary for public or low-sensitivity APIs.

6. Enough: The signature verifies source and ensures the update wasn’t modified. No confidentiality is needed since software is public.

7. Not enough: AES-CTR provides confidentiality, but without integrity or authentication, the message can be silently tampered or forged by attackers.

8. Enough: TLS provides all three: encrypted channel, tamper detection, and mutual or server-side authentication. This is appropriate for sensitive data.

The Curious Ciphertext

Background: ECB

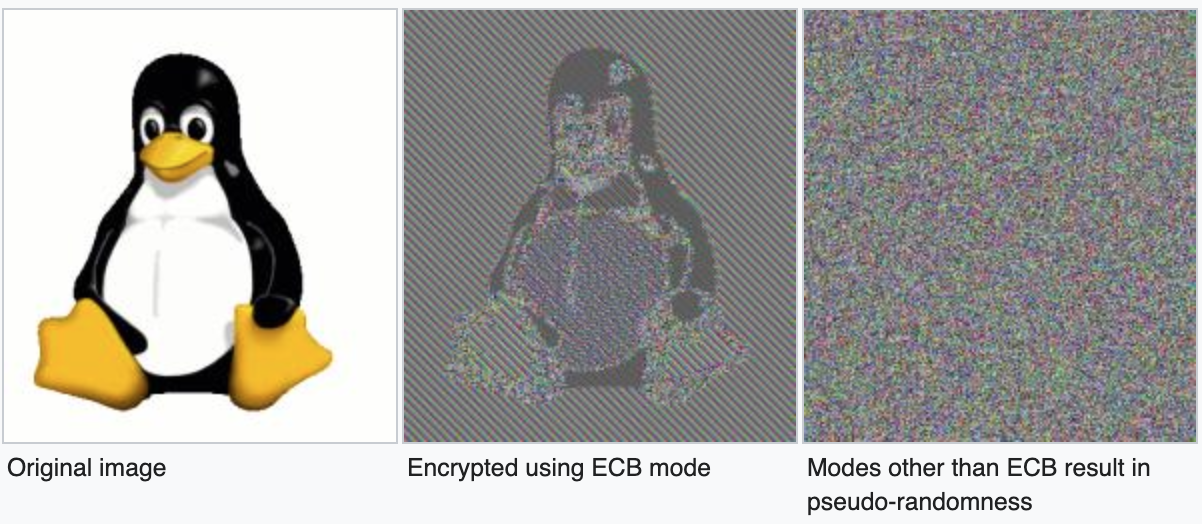

Encryption is supposed to conceal the structure of a message. However, not all modes of encryption achieve this. Electronic Codebook (ECB) is one of the simplest block cipher modes. It encrypts each block of plaintext independently using the same key. While this makes it easy to implement and parallelize, it has a serious flaw: if two plaintext blocks are identical, their ciphertexts will also be identical.

This weakness was famously demonstrated using the ECB Penguin. A bitmap image of the Linux penguin (Tux) was encrypted using AES in ECB mode. Although the image data was encrypted, the resulting encrypted file still visibly resembled the original image. The structure was preserved because repeating image blocks were encrypted to identical ciphertext blocks. This became a widely used cautionary example of why ECB mode is insecure for any structured data.

You will also have hands-on experience with this issue during the Python Cryptography Lab.

Scenario

You are analyzing traffic between a legacy client and a server. Messages are encrypted using AES-128 in ECB mode with a shared symmetric key. You capture two encrypted messages:

C1 = [0x5af3, 0x8c21, 0x5af3, 0x92b0, 0x5af3]C2 = [0x7da1, 0x5af3, 0x8c21, 0x8c21, 0x7da1]

You do not know the AES key or the plaintext, but the ciphertexts reveal repeating patterns.

Answer the following questions:

- What can you infer about the plaintexts of

C1andC2? - Which security property is violated in this situation?

- Would this problem still occur if the client switched to AES-CBC or AES-GCM mode with a new IV per message? Why or why not?

- Why might a developer still use ECB mode despite its flaws?

- How would you improve this system to ensure both confidentiality and integrity?

Hints:

- ECB encrypts each block independently.

- Identical ciphertext blocks mean identical plaintext blocks.

- Random IVs and chaining can break this pattern.

- Integrity requires more than just encryption.

The block 0x5af3 appears three times in C1 and once in C2, indicating repeated plaintext blocks. Similarly, 0x8c21 appears in both messages and twice in C2, suggesting a repeated message segment. The pattern 0x7da1 appears at both ends of C2, possibly framing the message.

This reveals a violation of confidentiality. ECB mode leaks information about plaintext structure because it produces identical ciphertext blocks for identical plaintext blocks.

This issue would not occur in CBC or GCM mode. Both introduce randomness via an initialization vector, and CBC chains ciphertext blocks together, so even repeated plaintexts result in different ciphertexts. GCM also adds authentication.

Developers may still use ECB mode for its simplicity. It is easy to implement, requires no IV management, and supports parallel encryption. In legacy systems or low-security applications, this might be mistakenly deemed acceptable.

The system should be updated to use AES-CBC or AES-GCM with a fresh IV per message. For full protection, AES-GCM is preferred because it provides both confidentiality and integrity. Key management and IV reuse prevention are essential.

In a secure system, it is not enough to hide the content of a message. The patterns within the data, such as repeated blocks or structures must also be obscured, or attackers may infer sensitive information **without** ever decrypting the payload.

One of the factors that contributed to the cracking of the Enigma cipher during World War II was the consistent and predictable use of phrases like “Heil Hitler” at the end of many military messages. This repeated plaintext, known as a crib, allowed Allied cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park to make educated guesses about parts of the plaintext and align them with known ciphertext segments. Because Enigma encrypted each letter deterministically and did not use secure modes to obscure repetition or structure, these known phrases provided critical footholds for deducing key settings. This demonstrates that even strong ciphers can be undermined when patterns in the plaintext are exposed, reinforcing the modern principle that secure systems must obscure structure as well as content.

The Graph of Trust

Background: Public Key Infrastructure Trust Chain

Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) allows users to verify the authenticity of entities using digital certificates. At the top of the hierarchy sits a Certificate Authority (CA), whose public key is trusted implicitly. Every certificate issued by the CA (or by another entity with delegated signing rights) creates a chain of trust.

This can be modeled as a directed graph, where each node represents a public key, and an edge from A to B means “A has signed B’s public key.” A public key is considered trusted if there exists a path from the root CA to that key. A path means that all certificates of intermediary nodes are available. If no such path exists, the key and the identity it belongs to is not trusted by the system.

For example, in the graph below:

[Root CA]

↓

[X]

↓

[Y]

If the client trusts only the Root CA, it can also trust X (because Root signed X) and Y (because X signed Y). But if a key is not reachable from the Root CA, the client cannot verify it and must treat it as untrusted.

In modern operating systems and browsers, a chain of trust is established through a built-in list of trusted root certificate authorities (CAs). These root CAs are hardcoded or bundled with the OS or browser and are implicitly trusted. When a user connects to a website over HTTPS, the browser receives a digital certificate issued to that website, along with intermediate certificates. The browser then verifies that this certificate was signed by a trusted CA or by an intermediate CA that itself has a valid signature chain back to a trusted root. If such a valid path exists, the certificate is considered trustworthy, and the connection proceeds securely. If the chain is broken or unverifiable, the browser warns the user or blocks the connection entirely.

Network of trust

A node’s public key is trusted if there’s a valid chain of signatures to the Root CA, and the client possesses the certificates for all nodes along that chain, including the node itself.

Scenario

You are given the following trust graph extracted from a distributed certificate system:

[Root CA]

|

[A]

/ \

[B] [C]

| |

[D] [E]

/

[F]

Each edge represents a digital signature, where the upper node has signed the public key of the lower node.

A client only trusts the Root CA initially and given the certificates of A (signed by Root), B (signed by A), C (signed by A), D (signed by B), and F (signed by E). Your task is to evaluate which keys are trusted and which are not.

Answer the following questions:

- Which of the nodes’ public keys are trusted from the client’s perspective?

- Can the client verify a message signed by F? Why or why not?

- Suppose a new signature is added: D signs F and the client is provided F’s certificate (signed by D). How does this change the trust graph? Is F now trusted?

- What is the risk of relying solely on this graph-based trust model in open networks?

- How does a compromised node like A or C affect the rest of the graph?

Hints:

- Paths must originate from the Root CA to be trusted.

- Signing someone’s key doesn’t imply the reverse.

- Trust is transitive only if the signature chain is valid and verifiable.

- Cycles do not break trust, but they don’t substitute for a root path.

A node’s key is trusted if there’s a valid chain of signatures to the Root CA, and the client possesses the certificates for every node in that chain, including the node whose key is being validated. These include A (signed by Root CA), B and C (signed by A), D (signed by B), and E (signed by C). The client possess' F's certificate that's signed by E, but does not have E's certificate. Therefore, the chain of trust is broken.

The client cannot verify a message signed by F, because there is no complete chain of signatures from the Root CA down to F as explained in the previous part.

If D signs F, and D is already trusted via Root → A → B → D, and the since the Client now has F's newly signed certificate (by D), then there exists a new path: Root → A → B → D → F. This makes F trusted by transitivity.

In open networks that rely solely on transitive trust graphs, significant security risks arise because trust is automatically extended through chains of signatures. One common attack involves compromising a trusted intermediate node. For example, if an attacker manages to obtain the **private** key of an intermediary such as node A, they can then generate and sign new public keys for **fake** entities. Since the clients trust node A and follow the transitive signature chain, they will also trust these newly signed malicious keys without realizing they are not legitimate. This allows the attacker to introduce entire branches of untrusted nodes into the trust graph, which can then be used for impersonation, phishing, or distributing malware.

Another way the trust graph can be exploited is through social engineering. An attacker might trick a trusted node’s operator into signing a key for an unverified or malicious party. This can happen if a trusted node does not strictly verify the identities of the parties whose keys it signs or if it is manipulated through phishing or deceptive requests. Once a trusted node signs an attacker’s key, the attacker immediately gains all the privileges and trust associated with the legitimate signature path, allowing them to masquerade as a trusted entity.

If a node like A is compromised, then all entities it signed (B and C), and those signed downstream (D, E, F), become potentially untrustworthy. This is called trust propagation. A single compromised node can corrupt the integrity of a **large** subtree of the trust graph.

Epilogue

This question is meant to highlight that the trust is only established when the client is able to construct and verify the full signature chain from the root CA down to C, with all necessary certificates in hand. Merely observing a trust graph or being told about a chain is insufficient. This is why browsers and other secure systems always require the actual certificate files and perform verification steps locally for every link in the chain.

For example, if A is a trusted root CA, and A signs B’s certificate, and B sign’s C certificate, a client can only trust C if:

- The client explicitly trusts A as a root CA (i.e., A’s public key is in the client’s trusted root store).

- The client possesses B’s certificate (which is signed by A). This allows the client to cryptographically verify that B’s public key is legitimate, using A’s public key.

- The client possesses C’s certificate (which is signed by B). This allows the client to verify that C’s public key is legitimate, using B’s public key.

- Each verification is performed locally: The client must actually perform the cryptographic verification (e.g., running

.verify()on each certificate’s signature), not simply trust the existence of the chain on paper or in a diagram.

How does this work in practice?

When we visit an HTTPS website, your browser receives the server’s certificate chain (usually the server cert + intermediates).

The browser checks the following:

- Is the certificate chain anchored in a root CA that the browser already trusts (its “root store”)?

- Can each certificate in the chain be cryptographically verified, link by link, from the root to the leaf?

- Are any of the certificates revoked or expired?

- Are the certificate details (domain name, usage, etc.) appropriate for the connection?

The browser performs all of these checks locally before establishing a secure connection.

Other applications that run verify:

- Operating Systems: For system-level trust (e.g., S/MIME email, code signing).

- Email clients: When verifying S/MIME or PGP-signed messages.

- Command-line tools: Like

openssl verify,curl,wget,git, etc., when connecting to servers over TLS/SSL. - APIs and SDKs: Any app using SSL/TLS libraries (like OpenSSL, GnuTLS, Windows SChannel) will usually call verification routines when connecting securely.

But for almost everyone, the browser is the most visible and important example of automatic, local certificate verification.

Technical Example

Here’s a simple example on how to verify a certificate on your own computer. Suppose you have:

rootCA.pem(Root CA certificate, trusted by client)intermediate.pem(Intermediate cert, signed by Root CA)server.pem(Leaf certificate, signed by intermediate)

Method 1: Manual Verification with OpenSSL (command-line)

openssl verify -CAfile rootCA.pem -untrusted intermediate.pem server.pem

This verifies that server.pem is valid, using rootCA.pem as the root trust anchor and intermediate.pem as the intermediate.

Method 2: Python Example with cryptography Library

from cryptography import x509

from cryptography.hazmat.backends import default_backend

from cryptography.x509 import Certificate

from cryptography.x509.oid import NameOID

from cryptography.x509 import CertificateRevocationList

from cryptography.hazmat.primitives import serialization

def load_cert(filename):

with open(filename, 'rb') as f:

return x509.load_pem_x509_certificate(f.read(), default_backend())

# Load certificates

root_cert = load_cert('rootCA.pem')

intermediate_cert = load_cert('intermediate.pem')

server_cert = load_cert('server.pem')

# To actually build and verify a chain, you’d use a library that supports path validation.

# cryptography (as of July 2025) does not provide a full path builder.

# You can, however, check the signature "by hand" for illustration:

# Step 1: Verify that intermediate was signed by root

root_public_key = root_cert.public_key()

try:

root_public_key.verify(

intermediate_cert.signature,

intermediate_cert.tbs_certificate_bytes,

intermediate_cert.signature_hash_algorithm

)

print("Intermediate signed by Root: VALID")

except Exception as e:

print(f"Intermediate signed by Root: INVALID: {e}")

# Step 2: Verify that server was signed by intermediate

intermediate_public_key = intermediate_cert.public_key()

try:

intermediate_public_key.verify(

server_cert.signature,

server_cert.tbs_certificate_bytes,

server_cert.signature_hash_algorithm

)

print("Server signed by Intermediate: VALID")

except Exception as e:

print(f"Server signed by Intermediate: INVALID: {e}")

# Note: This example is over-simplified. Real-world applications require revocation checking, path constraints, and more.

In summary:

- Browsers and secure apps automatically perform these steps for every link in the certificate chain, not just visually trusting a diagram.

- Tools like

openssl verifyor libraries like Python’scryptographylet us perform the same verification locally.

You will have hands-on experience on verifying certificates before establishing a secure connection in your programming assignment.

RSA in Action

Background: RSA Arithmetic

RSA is a public key cryptosystem based on modular arithmetic. It uses a public key (n, e) for encryption or signature verification, and a private key (n, d) for decryption or signing. The security relies on the difficulty of factoring large numbers.

The keys are derived from two large primes, p and q:

- Compute

n = p × q - Compute Euler’s totient

φ(n) = (p - 1)(q - 1) - Choose public exponent

esuch thatgcd(e, φ(n)) = 1 - Compute private exponent

dsuch thate × d ≡ 1 (mod φ(n))

Encryption: c = m^e mod n

Decryption: m = c^d mod n

Signing: s = m^d mod n

Verification: m = s^e mod n

Small examples can be used to practice and verify understanding, even though real RSA uses numbers with hundreds or thousands of bits.

Scenario

A server uses RSA to secure client data. The public key is:

n = 221e = 11

A client sends the encrypted message c = 55.

Answer the following questions:

- Given that

n = 221was generated usingp = 13andq = 17, compute the private exponentd. - Decrypt the ciphertext

c = 55to recover the original plaintext messagem. - If a client wants to sign a message

m = 25, what is the resulting signatures? - Why is RSA not used directly to encrypt large files or streams of data?

- How does padding (like OAEP) strengthen RSA encryption?

Hints:

- Use Euler’s totient φ(n) = (p − 1)(q − 1)

- Compute d such that (e × d) mod φ(n) = 1

- For small numbers, try brute-force or use extended Euclidean algorithm

- Modular exponentiation is key to RSA security

First, compute φ(n) = (13 - 1)(17 - 1) = 12 × 16 = 192. We want to find d such that 11 × d ≡ 1 (mod 192). Testing small values, we find d = 35, because 11 × 35 = 385 and 385 mod 192 = 1.

To decrypt c = 55, compute m = 5535 mod 221. Modular exponentiation efficiently computes this large exponentiation by repeatedly squaring and reducing modulo 221 at each step, resulting in m = 217. This is the original plaintext.

To sign m = 25, compute s = 2535 mod 221. Using the same efficient modular exponentiation method, we obtain s = 155. This is the digital signature.

RSA is inefficient for large files because encryption and decryption involve expensive exponentiation with large numbers. Also, RSA can only operate on messages smaller than the modulus n. In practice, RSA is used to encrypt small secrets like symmetric keys, and the rest of the data is encrypted with a faster symmetric cipher.

Padding schemes like OAEP add randomness and structure to the message before encryption, preventing attackers from exploiting deterministic output. Without padding, RSA is vulnerable to dictionary attacks and other forms of cryptanalysis.

Epilogue

The following python code solves the questions above efficiently. Note that during exam, we will give you small values of p and q such that it is doable manually or with a simple calculator.

from sympy import mod_inverse # install sympy for this test code

p = 13

q = 17

n = p * q

e = 11

c = 55

m_to_sign = 25

# compute Euler's totient

phi_n = (p - 1) * (q - 1)

# compute private exponent d

d = mod_inverse(e, phi_n)

# decrypt the ciphertext c with private key (d,n)

m = pow(c, d, n)

# compute signature with private key (d,n)

# note that computation of both ciphertext and signature uses private key (d, n)

signature = pow(m_to_sign, d, n)

print(d, m, signature)

The Compromised Broadcast

Background: Digital Signatures

In many systems, messages are digitally signed but not encrypted. This ensures the receiver can verify the authenticity of the sender and the integrity of the message but the contents remain visible to anyone listening.

This model works well when confidentiality is not critical, such as in software updates or public news feeds. However, if an attacker can inject or replay old signed messages, systems that do not perform freshness checks may behave incorrectly.

Digital signatures verify that a message was not modified and was signed by the correct private key. They do not guarantee that the message is recent, relevant, or safe to reuse.

Scenario

A command center broadcasts signed control messages to multiple unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Each message includes the command and a digital signature using the control center’s private key. The messages are not encrypted, and each UAV accepts any message with a valid signature.

An attacker records the message:

"Return to base"

Signature: valid

Hours later, the attacker replays this signed message during an ongoing operation.

Answer the following questions:

- What guarantees does the digital signature provide in this system?

- Why is the replayed message still accepted by the UAVs?

- What property is missing that allows this attack to succeed?

- Suggest a design fix that preserves integrity but also prevents replay attacks.

- If confidentiality was also required, what additional changes would you make?

Hints:

- Signatures verify origin and integrity, but not timeliness

- Adding nonces, sequence numbers, or timestamps can help

- Replay attacks exploit stateless or timestamp-free systems

- Encryption can hide the message but does not replace signature checks

The digital signature guarantees that the message was created by the control center and was not modified in transit. It ensures authenticity and integrity, but not freshness or context.

The message is accepted because it still has a valid signature from the trusted sender. The UAVs do not distinguish whether the message is new or old, since there is no timestamp, nonce, or sequence number to indicate freshness.

The missing property is message freshness. Without a way to detect whether a message is outdated or already processed, the system is vulnerable to replay attacks.

A good fix would be to include a timestamp or sequence number in the message and require each UAV to track the most recent message it has processed. The signature must cover the timestamp or sequence number to prevent tampering.

If confidentiality is also needed, the messages should be encrypted using a symmetric session key established beforehand, possibly via public key exchange. This ensures that only the intended UAVs can read the message, while digital signatures continue to ensure authenticity and integrity.

Replay Riches

Background: Message Authentication Codes

Message Authentication Codes (MACs) are used to ensure data integrity and authentication over insecure channels. A MAC is computed over the message using a shared secret key, and the receiver verifies it to ensure the message has not been tampered with.

For example, when the client prepares the message “Pay SGD 100 to Merchant A”, it computes a MAC using a cryptographic hash function (like SHA-256) combined with the shared secret. This produces a fixed-length tag that acts like a fingerprint for the message. The message and its MAC are sent together to the server.

- Upon receiving the message, the server uses the same secret key to recompute the MAC and compares it with the one received.

- If they match, the server knows the message was not tampered with and came from someone who knows the key, presumably the legitimate client.

However, if an attacker copies the exact same (message, mac) pair and sends it again, the server will perform the same MAC check and accept it, unless it has a way to detect that this is not a new request.

This shows that MACs do not prevent replay attacks by themselves. If a valid (message, MAC) pair is captured and sent again later, a system that doesn’t track freshness or ordering will accept it again, even if the original message was only intended to be used once.

Scenario

An online payment system uses HMAC-SHA256 with a shared secret between the client and server. When a customer clicks “Pay SGD 100 to Merchant A,” the client sends:

message: "Pay 100 to Merchant A"

mac: HMAC(secret, message)

The server verifies the MAC and processes the payment.

An attacker sniffs the network and captures this (message, mac) pair. Later, the attacker resends it to the server. Since the MAC is still valid, the server processes the same SGD 100 payment again.

Answer the following questions:

- Why does the MAC still verify correctly on the second attempt?

- What important security property is violated in this attack?

- How can the server distinguish between original and replayed messages?

- Suggest two different protocol changes that would prevent this replay.

- Would encrypting the message fix the problem? Explain.

Hints:

- MACs only prove integrity and origin, not uniqueness or timing

- Nonces, timestamps, or counters are often used to track freshness

- Encryption without integrity does not prevent replays

- Think about stateful vs stateless designs

The MAC verifies correctly because it was computed using the correct secret and message. Since the attacker simply replayed the exact same message and MAC, the server sees it as valid.

The attack violates authentication freshness. While the MAC ensures that the message originated from the legitimate client and was not tampered with, it does not prove that the message is recent or intended to be processed again.

The server needs a way to detect whether the message has already been processed. This can be done using unique transaction IDs, sequence numbers, or timestamps included in the message and verified against a record of previously seen values.

One solution is to add a unique nonce or payment ID to each transaction and reject duplicates. Another is to include a timestamp in the message and enforce an expiration window, combined with MAC verification. In both cases, the freshness data must be included in the MAC computation.

Encrypting the message without changing its contents or adding freshness data does not help. The attacker can replay the same ciphertext. Confidentiality does not imply integrity or uniqueness. Without tracking freshness, the system remains vulnerable to replays.

When Integrity Isn’t Enough

In some systems, data is encrypted or MACed correctly: ensuring confidentiality and integrity. But there’s no authentication: no proof of who sent the data. Sometimes this is acceptable (e.g. anonymous whistleblowing). In other cases, it leaves the system open to spoofing, impersonation, or replay attacks.

Understanding what security property matters in a context is as important as applying crypto correctly! In exam settings, you should read the requirements properly.

Scenario

An anonymous reporting tool allows users to submit incident reports via an HTTPS POST request. To protect privacy and detect tampering, the client:

- Compresses the report.

- Encrypts it using the server’s public RSA key.

- Computes a SHA-256 hash of the plaintext and includes it in a header.

- Sends the encrypted report and the hash to the server.

The server decrypts the message using its private key and checks the SHA-256 hash to ensure the report wasn’t tampered with.

Answer the following questions:

- Does this scheme provide confidentiality? Why or why not?

- Does it provide integrity? Are there any caveats?

- Is authentication required in this use case? Why or why not?

- What attacks, if any, are still possible?

- Suggest modifications if this system were used for sensitive commands instead of anonymous reporting.

Hints:

- Think about: who can send? who is the recipient? does it matter?

- SHA-256 alone doesn’t stop intentional forgery

- Public-key encryption only proves receiver identity, not sender

The system provides confidentiality because the message is encrypted using the server’s public RSA key. Only the server can decrypt it with its private key, so eavesdroppers cannot read the report.

It offers basic integrity via the SHA-256 hash, but this is not sufficient to prevent intentional tampering. Anyone can recompute the hash over altered content and submit a forged pair. A secure integrity check would require a MAC using a secret key.

Authentication is not required in this use case because the goal is anonymous reporting. The system is designed to protect the reporter’s identity, not verify it.

However, the system is vulnerable to abuse anyone (including attackers or bots) can submit fake reports or spam the server. The server also cannot trace repeated reports from the same source or limit malicious use.

If this system were used for sensitive actions like issuing commands or submitting transactions, authentication would be essential. In that case, each client should authenticate using a digital signature or client-side certificate, and integrity should be enforced using HMAC or AEAD rather than plain hashes.

Sign Before You See

Digital signatures are used to assert that a piece of data originated from a trusted signer and has not been tampered with. However, signing only proves that a private key was used, and it does not imply that the signer agrees with or even understands the content unless proper verification steps are in place.

If a system blindly signs data without reviewing its contents, it can unintentionally become a signing oracle, enabling attackers to forge valid-looking claims with the system’s authority behind them.

In class, we learned that digital signatures provide non-repudiation, meaning the signer cannot later deny having signed a message. But this property only proves that a particular private key was used, not that the signer read, understood, or agreed with the contents. In systems where users can submit arbitrary data for signing, non-repudiation does not imply endorsement.

This distinction is critical: a signature may confirm origin and integrity, but without content verification, it says nothing about intent or consent.

Scenario

A startup builds a blockchain-based document notarization service. Clients submit any document, and the server returns a signed hash of that document using the service’s private key. This is meant to prove that “the document existed at a certain time.”

One day, an attacker submits the following message:

"I, the owner of the service, hereby transfer 100% control of the company to the bearer of this document."

The server returns a valid signature over the hash of this message.

The attacker now presents the signed message in court, claiming it is legally binding, because it was signed by the service’s private key.

Answer the following questions:

- What does the signature prove, and what does it not prove?

- Why is this behavior dangerous for the server?

- How could an attacker abuse such a system repeatedly?

- What policy or technical measure could prevent this misuse?

- If signing cannot be avoided, what disclaimers or structural safeguards should be added?

Hints:

- Signatures verify authenticity and integrity, but not endorsement

- In real life, systems must separate signing from attestation or approval

- Think about user-submitted input and legal implications

- Consider the difference between “notarizing” and “agreeing”

The signature proves that the service's private key was used to sign the hash of the document. It confirms the document existed in that exact form at the time of signing. However, it does not prove that the service agrees with or endorses the content.

This is dangerous because third parties (including courts) may interpret a digital signature as an endorsement or approval. If the service does not verify the contents, it can be tricked into signing malicious, misleading, or fraudulent claims.

An attacker could repeatedly submit documents with deceptive claims or forged declarations, obtaining valid signatures that appear to come from a legitimate authority. These can then be used for impersonation, contract fraud, or misinformation.

The server should never sign arbitrary user content without human or automated verification. Instead, it could require a formal request format, include metadata stating that the document was user-submitted, or use a separate signing key for unverified materials.

If signing cannot be avoided, the signature should include a clear disclaimer like “This document was notarized but not reviewed or approved by the service.” Structurally, the service can sign only a standard header or hash block with explicit boundaries and timestamps to limit liability.

Timing the Leak

Encryption protects data by scrambling its contents, making it unreadable without the correct key. However, encryption often does not hide metadata, such as packet sizes, transmission timing, or connection frequency. In some cases, this metadata can be exploited to infer sensitive user behavior, even if the payload remains encrypted.

This is known as a side-channel attack, where information is leaked not from the decrypted message, but from how and when messages are sent. Timing attacks, packet size analysis, and traffic shape inference are all examples.

This is especially relevant in high-performance systems like VPNs, secure routers, or TLS connections that still emit observable patterns.

Scenario

A secure medical web app encrypts all its traffic using HTTPS. However, an attacker positioned between a patient and the server captures the following:

- Requests are small and sporadic during idle periods

- Suddenly, a large

POSTrequest is made - Followed by a series of regularly sized responses over 15 minutes

The attacker, despite not decrypting any messages, guesses that the user has just started a video consultation with a doctor!

Answer the following questions:

- How was the attacker able to infer user activity despite HTTPS?

- What exactly was protected by encryption, and what was exposed?

- Suggest a protocol-level mitigation to obscure such traffic patterns.

- How does this relate to performance and buffering tradeoffs?

- Would padding all packets to the same size solve this problem? Why or why not?

Hints:

- TLS protects content, not size, timing, or frequency

- Traffic shaping or timing obfuscation can help

- Bandwidth, latency, and CPU use are often affected by padding

- Metadata can leak behavioral or contextual information

The attacker used traffic patterns. Specifically, the sudden increase in payload size and consistent response timing to infer the **beginning** of a video session. This side-channel observation reveals user behavior even though the message content is encrypted.

HTTPS protects the payload contents from being read or altered, but it does not conceal packet sizes, transmission times, or flow frequency. These aspects remain visible to any observer on the path between client and server.

One mitigation is to use traffic shaping, such as sending fixed-size packets at regular intervals regardless of actual data, or adding dummy traffic to obscure the true communication pattern. VPNs and onion routing protocols sometimes apply this technique.

These countermeasures reduce information leakage but introduce performance costs. Constant-rate transmission can increase latency and waste bandwidth, especially for low-traffic users. Systems must balance privacy with resource efficiency.

Padding all packets to the same size only hides the size of individual messages, but not timing or frequency. It helps mitigate some pattern leaks but cannot eliminate all side channels unless combined with timing controls and randomized dummy traffic.

🧅 Onion Routing

Onion routing is a technique used to achieve anonymous communication over a network by layering encryption, like the layers of an onion. In this model, a message is encrypted multiple times, each layer intended for a different node in a chain of relays. As the message passes through each relay, one layer of encryption is removed, revealing only the identity of the next node. No single relay knows both the sender and the final destination. This layered design prevents eavesdroppers and intermediaries from linking source and destination directly, making onion routing a core technology behind systems like Tor, which aim to provide privacy, anonymity, and resistance to traffic analysis.

Read more about it here if you are interested.

Fast Enough?

Not all systems require full confidentiality, integrity, and authentication. Sometimes, performance is critical, and you only need one or two of the CIA properties: especially for low-power embedded systems, real-time messaging, or public broadcasts.

Choosing the right cryptographic tool requires understanding both what you need to protect and how fast different primitives perform.

Scenario

A company is designing a high-frequency event stream from IoT sensors (like temperature spikes or door opens). These alerts are broadcast to a shared cloud server every 50 ms from hundreds of devices. The data is not secret, but the server must know:

- The message came from a legitimate device (authentication).

- The message wasn’t tampered with (integrity).

- But speed is critical! The devices are low-power and the cloud must handle high load.

The team is evaluating the following combinations:

| Option | Crypto Used | Provides | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | HMAC-SHA256 | Integrity, Authentication | Medium |

| B | AES-GCM with random nonce | Conf, Integrity, Auth | Low |

| C | Ed25519 signature + plaintext message | Authentication only | High |

| D | CRC32 checksum + AES-CTR | Conf only | Very High |

| E | Plaintext + SHA-256 digest | Integrity (unkeyed) | High |

Answer the following questions:

- Which option satisfies the system’s needs without over-protecting?

- Which option is cryptographically insufficient? Why?

- If option C is used, how can the server verify that a message was not replayed?

- Suppose the message includes a timestamp and device ID. How does that affect security?

- What tradeoffs would justify choosing option A over option C?

Hints:

- Think about whether integrity without keys is enough

- Signatures are slower than HMACs but provide public verifiability

- Does AES make sense if you don’t need secrecy?

Option C (Ed25519 signature + plaintext) is the best match. It provides authentication (proves the sender’s identity) and implicit integrity (a valid signature won't verify over a tampered message), without encrypting or adding unnecessary overhead. Its throughput is high and fits the system’s need for speed and authenticity.

Option E is cryptographically insufficient. A SHA-256 digest is not keyed, so an attacker can tamper with the message and recompute the digest. There's no way to detect forgery or impersonation.

To prevent replays in option C, each message can include a monotonic timestamp or nonce. The server can keep track of recently seen values to reject duplicates.

Including a timestamp and device ID helps the server trace events and prevent replay attacks, but the timestamp must be signed, otherwise, an attacker could forge a message with fake timing.

Option A (HMAC-SHA256) is also valid but uses a symmetric key. It's suitable when both parties share a secret key securely. It’s slightly slower but more efficient on constrained devices that can't do public-key cryptography. It would be chosen if the signer must be very lightweight or if key rotation is tightly managed.

The Hijacked Port

Background: Port Numbers

At the transport layer, protocols like TCP use port numbers to distinguish between different services on the same host. A port is like a logical endpoint on a machine (or virtual machine) as we learned before, for example, port 443 is used for HTTPS, while port 22 is for SSH.

When an application binds to a port, it listens for incoming connections. The OS kernel maps packets arriving at that port to the application socket that owns it.

However, if an attacker manages to bind to a port before the legitimate service, they may receive sensitive incoming traffic. This is known as a port hijacking or pre-binding attack. Even if encryption is in place, the traffic is misrouted.

Scenario

A hospital’s internal system includes a backend service that encrypts sensitive patient reports and sends them to a reporting client on port 7000. The client program is supposed to be launched first and binds to port 7000 to receive the data.

However, a local attacker runs a malicious program that binds to port 7000 before the legitimate client. The server now sends the encrypted reports to the attacker’s process.

Although the attacker cannot decrypt the reports, they store all incoming traffic for future cryptanalysis or potential key compromise.

Answer the following questions:

- Why is the attacker able to receive the data despite the server using encryption?

- What OS-level mistake allowed this hijack to succeed?

- Suggest a design that prevents unauthorized processes from hijacking critical ports.

- How could a process authenticate the receiving party before sending encrypted data?

- What general security principle is violated in this scenario?

Hints:

- Encryption doesn’t stop traffic from going to the wrong destination

- Port access is typically first-come, first-served unless controlled

- Consider capabilities, user privilege, or handshake authentication

- Think about endpoint validation, not just encryption

The attacker is able to receive the data because they bound to the expected port before the legitimate client did. The server does not verify who is listening, as it simply sends data to port 7000 on the client machine, assuming it’s correct.

The OS allowed any user-level process to bind to port 7000. There was no access control or reservation mechanism preventing unprivileged or malicious programs from occupying the port first.

One solution is to run the legitimate client as a privileged service that reserves the port at boot time. Alternatively, the OS could enforce capability-based controls, only allowing certain programs or users to bind to specific ports.

To prevent this class of attack, the sending process should not blindly trust the port. It should require an authenticated handshake before transmitting sensitive data. Mutual TLS, signed challenges, or application-layer tokens can validate the receiver’s identity before sending encrypted payloads.

This scenario violates the principle of **secure binding** and **trust minimization**. Encryption alone is not sufficient as the sender must ensure that messages are delivered to the **correct**, **authenticated** recipient before assuming the channel is secure.

One Hash Too Many

Background: Collision in Hashing

Most digital signature algorithms (like RSA or ECDSA) do not sign the full message directly. They sign a cryptographic hash (digest) of the message. This is faster and allows signatures to handle variable-length input.

However, this approach assumes the hash function is collision-resistant, that is, it should be computationally infeasible to find two different messages m1 ≠ m2 such that hash(m1) = hash(m2).

If a signer blindly signs the hash without knowing what the original message was, and if the hash function is weak, an attacker could create a collision pair: one harmless document and one malicious document with the same digest. The signer sees and signs the harmless one, but the attacker presents the malicious one with the valid signature.

This has occurred in the real world with MD5 and SHA-1.

Scenario

A notary service agrees to sign any file by computing its SHA-1 hash and returning an RSA signature over that hash. A user submits:

File A: “Agreement between Alice and Bob to pay $1.”

The service signs SHA1(File A) and returns the signature.

Later, Bob presents:

File B: “Agreement between Alice and Bob to pay $1,000,000.”

The two files have different contents but were carefully crafted to collide under SHA-1. The signature for File A is now valid for File B.

Answer the following questions:

- Why does this attack succeed, even though RSA is mathematically secure?

- What specific property of SHA-1 was exploited?

- How could the service have prevented this attack, even while still using RSA?

- Should hash functions be trusted forever once approved? Why or why not?

- How do modern signing standards defend against this kind of forgery?

Hints:

- Think about collision resistance vs pre-image resistance. Search it online or read this section of the notes.

- Signing a digest assumes trust in the hash function

- Consider double hashing or domain separation in modern schemes

- Look up SHA-2, SHA-3, and collision exploits in MD5 or SHA-1

The attack succeeds because the notary signed only the SHA-1 hash of the file, and the attacker submitted a file that was part of a known collision pair. RSA correctly signed the hash, but that hash was shared by both the harmless and malicious documents.

This exploited a weakness in SHA-1's collision resistance, which means an attacker can generate two different messages with the same hash. Once a collision is found, the same signature validates both.

The service should have stopped using SHA-1 and moved to a stronger hash function like SHA-256 or SHA-3. It should also sign structured messages or use modern signing protocols that include metadata to prevent interchangeable content.

Hash functions should not be trusted indefinitely. Cryptanalysis improves over time, and once collisions or weaknesses are discovered, continued use opens systems to forgery attacks like this. MD5 and SHA-1 are now considered insecure.

Modern digital signature standards (like RSASSA-PSS or ECDSA over SHA-256) use padding, randomized hashing, or structured input formats that prevent attackers from creating meaningful collisions. They also typically include protocol-specific context to bind the signature to its intended use.

Padding Oracle

Background: CBC and the Attack

In block cipher modes like CBC (Cipher Block Chaining), encryption requires plaintext to be a multiple of the block size (e.g., 128 bits). When the message is shorter, it’s padded (e.g., using PKCS#7). On decryption, the receiver removes the padding and checks if it’s valid.

If an attacker can send tampered ciphertexts to a server and observe whether the padding check fails or succeeds, they can learn information about the plaintext, one byte at a time. This is known as a padding oracle attack.

Even though the encryption algorithm (e.g., AES) is secure, leaking error information gives attackers a powerful side channel.

Padding Oracle Attack Example

Assume AES-CBC with 16-byte blocks and PKCS#7 padding. The server receives two ciphertext blocks:

C1: [AA BB CC DD EE FF 00 11 22 33 44 55 66 77 88 99]

C2: [FA 5B 91 00 4C 8D 3A 7E 21 76 9A 0B 17 29 5C 01] ← Last byte ends in 0x01

Let’s say C2 is the final block, and C1 is the IV for decrypting C2.

On decryption:

- The server computes

P2_raw = AES_decrypt(C2). Suppose this yields (not known to attacker):P2_raw = [CB A1 9E 77 5A 33 B2 C7 1B C4 12 A0 1D 55 4F 04] - Then it computes

P2 = P2_raw XOR C1. (This produces the actual plaintext block). - The server then checks the padding. The last byte of

P2is0x04. If all of the last 4 bytes are0x04, the padding is valid.

The Attack

The attacker cannot decrypt the block directly but can modify C1 and resend the ciphertext to the server.

They:

- Flip the last byte of

C1(e.g., change0x99→0x98) - Send

[modified C1] + C2to the server - Observe the response:

- If the server returns “invalid padding”, it means the new last byte of

P2is not a valid0x01 - If it returns “MAC failed” (but padding passed), attacker knows they hit a valid padding (

0x01)

- If the server returns “invalid padding”, it means the new last byte of

By doing this repeatedly, they figure out what byte must be in C1 to make P2[-1] = 0x01 (the last byte, i.e. index -1, of that P2 plaintext block), allowing them to compute:

P2_raw[-1] = C1[-1] XOR P2[-1]

= known_value XOR 0x01

Since attacker knows what they flipped C1[-1] to, they recover P2_raw[-1], and from there compute P2[-1].

They repeat for second-last byte (0x02 0x02), third-last, etc., recovering the entire last block byte by byte, without decrypting AES.

Scenario

A server receives encrypted data over HTTPS. Internally, it decrypts incoming ciphertext using AES-CBC and returns an error if the padding is invalid:

Error 1: Invalid paddingError 2: MAC verification failed

An attacker sends a modified ciphertext and observes the error message. By systematically tweaking ciphertext blocks and watching for “Invalid padding” vs “MAC failed”, the attacker recovers one byte of plaintext at a time without ever knowing the encryption key.

Answer the following questions:

- What design flaw allows the attacker to decrypt the message without the key?

- How does the attacker learn about the plaintext from the padding error?

- What change to the server’s behavior could prevent this attack?

- Would switching to AES in ECB mode solve the problem? Why or why not?

- What modern cipher modes avoid this vulnerability?

Hints:

- Look at how CBC decrypts and applies XOR with previous block

- PKCS#7 padding is predictable and can be brute-forced

- Don’t reveal whether padding or MAC failed

- Authenticated encryption (AEAD) is designed to prevent this

The attack works because the server leaks internal validation steps. By returning different error messages for padding failure and MAC failure, it creates a decryption oracle that the attacker can probe.

The attacker manipulates the ciphertext and resends it. If the error is “invalid padding,” the guess was wrong. If the error changes, they know the padding is valid, revealing information about the original plaintext through CBC’s XOR structure. Repeating this narrows down the correct byte.

The server should return a generic error message regardless of whether the padding or MAC check failed. It should process both steps (decrypt, then MAC verify) before failing, without revealing where it failed.

Switching to AES-ECB would prevent the padding oracle, but at the cost of leaking plaintext structure. ECB mode is insecure because it produces identical ciphertext blocks for identical plaintext blocks.

A better fix is to use a modern authenticated encryption mode like AES-GCM or ChaCha20-Poly1305 (please search it online on your own if you are interested), which combines encryption and integrity checking in a way that avoids such side channels entirely.

Man in the Middle Manager

Background: MITM

Encryption ensures that data cannot be read by third parties, but it does not guarantee who you’re talking to. Without authentication, such as verifying a TLS certificate or SSH host key, a user can be tricked into connecting to an attacker who intercepts the communication, decrypts it, and passes it along. This is a man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack.

These attacks are especially dangerous in corporate or public Wi-Fi environments, where attackers control the local network and can impersonate legitimate services.

TLS Certificate

When your browser connects to a secure website, it receives a TLS certificate that contains the website’s public key, signed by a Certificate Authority (CA), which you have learned in class. The CA’s signature assures the browser that this public key really belongs to the claimed domain. The private key, which proves ownership of that public key, stays hidden on the server and is never sent over the network. The client never sees the private key it only trusts that the public key is valid because a trusted CA signed it.

SSH TOFU

In SSH, trust is established differently than TLS. When you connect to a server for the first time, your SSH client receives the server’s host public key and typically asks if you want to trust it. If you accept, the key is saved to a local

known_hostsfile. On future connections, the client checks that the server presents the same key. If it changes, the client warns you that the server might be compromised or spoofed.This model is called Trust On First Use (TOFU). You trust the key the first time you see it and watch for unexpected changes afterward. More secure setups preload trusted host keys or use SSH certificates signed by a known authority.

Scenario

A startup employee connects to the company’s internal admin dashboard over HTTPS. The domain internal.startup.com resolves locally, and the browser warns:

⚠ Your connection is not private. Proceed anyway?

The employee clicks “Proceed” to get their work done. Unbeknownst to them, a disgruntled IT manager has set up a rogue server with a self-signed certificate and is intercepting all requests. Because the employee skipped certificate validation, all login credentials, internal configs, and messages are now exposed despite the use of HTTPS.

Answer the following questions:

- Why did encryption fail to protect the user’s credentials?

- What should the client have verified before sending sensitive data?

- How does a self-signed certificate enable MITM?

- Suggest two ways to prevent such attacks in real-world networks.

- Why is SSH’s “first time connect” model risky? How can it be hardened?

Hints:

- TLS needs both encryption and authentication

- Browsers use CA trust stores; SSH uses known_hosts

- Always verify the identity of the other party

- Public key pinning, HSTS, or TOFU models can help

Encryption failed because the client skipped the certificate validation step. Without authenticating the server’s identity, the user had no guarantee they were speaking to the legitimate server, and the encrypted connection was established with the attacker instead.

The client should have verified that the server presented a valid TLS certificate signed by a trusted certificate authority (CA), matching the domain `internal.startup.com`. This ensures the encryption is not just secure, but also with the correct party.

A self-signed certificate allows the attacker to act as their own CA. Since the attacker controls the network and DNS resolution, they can present a certificate for the expected domain, and unless the client rejects it, the connection appears legitimate.

To prevent such attacks, organizations should use internal CAs and install them on client devices, or configure strict HSTS and certificate pinning policies. Networks should also monitor for unauthorized TLS endpoints and enforce mutual TLS when possible.

SSH uses a "trust on first use" (TOFU) model where the host key is stored after the first connection. This is risky if an attacker intercepts the initial connection. It can be hardened by preloading known host keys, verifying fingerprints manually, or using SSH certificates with a trusted authority.

Dual Use Danger

Background: Danger of Reusing Keys

In secure systems, it’s common to use both encryption (for confidentiality) and MACs (for integrity/authentication). Best practice is to use separate keys: one for encryption, and another for the MAC. This separation ensures that the operations remain independent and resistant to key-reuse attacks.

However, if the same key is used for both purposes, for example, AES for encryption and HMAC-SHA256 for integrity, the security of both mechanisms can be compromised.

This is called a dual-use key and is explicitly warned against in cryptographic standards.

Scenario

An IoT device uses a symmetric key K shared with the server to both:

- Encrypt sensor data using AES-CBC with K

- Compute a MAC over the ciphertext using HMAC-SHA256 with K

To save memory, the designers reuse the same key K for both. An attacker captures many encrypted messages along with their MACs. They cannot decrypt the ciphertext but begin crafting their own messages and observing how the MAC behaves under trial guesses.

Eventually, they exploit the key reuse to forge a valid ciphertext-MAC pair, which is accepted by the server, bypassing both confidentiality and integrity checks.

Answer the following questions:

- What’s wrong with using the same key for both encryption and MAC?

- How does key reuse increase the risk of forgery?

- What’s the cryptographic principle violated here?

- Suggest a safer design using symmetric cryptography.

- Why do AEAD ciphers like AES-GCM avoid this issue entirely?

Hints:

- Think about domain separation: MAC and encryption have different input/output structures

- Reusing keys gives attackers more known input/output pairs

- AEAD combines encryption and authentication securely in one mode

Using the same key for both encryption and MAC violates the principle of key separation. The operations have different mathematical structures and security assumptions, and combining them under a single key creates unintended interactions.

Key reuse gives the attacker more information: they can observe how the same key behaves under both encryption and MAC, and use chosen-ciphertext or chosen-message attacks to narrow down the key space or forge valid outputs.

This breaks the principle of domain separation: different cryptographic functions should use independent keys or at least ensure they’re distinguishable by context.

A safer design would use two separate keys derived from a master secret: one for AES-CBC encryption (`K_enc`) and one for HMAC-SHA256 (`K_mac`). Even better, keys should be generated or derived using a secure KDF with labels to indicate their role.

AEAD ciphers like AES-GCM or ChaCha20-Poly1305 (please search online on your own) handle both encryption and authentication in one integrated process using a single key, but they’re carefully **designed** to avoid **collisions** and interaction flaws. This eliminates the risk of dual-use key mistakes.

Crypto Soup

This question is challenging. It requires knowledge from various domains of cybersecurity where you are given a scenario and are supposed to find cryptographic weakness in the design.

In real-world systems, cryptographic components are rarely isolated. They’re mixed together: encryption, signatures, MACs, key exchanges, often under time pressure and without full understanding of their interactions. Even if individual parts seem “secure,” poor integration can undermine everything.

Understanding how to audit a design holistically is a crucial skill in system security.

Scenario

Your team is reviewing a proposed design for an encrypted messaging protocol used in a legacy IoT platform:

- Each device has a shared symmetric key

Kwith the server.- Messages are encrypted using AES-CBC with PKCS#7 padding.

- The same key

Kis also used to compute HMAC-SHA1 over the ciphertext.- IVs are generated using the system time in seconds.

- Devices cache a signed “firmware OK” certificate from the server, signed using RSA with SHA-1.

- Devices accept the certificate as long as the signature is valid, even if it’s expired or revoked.

You’re asked to comment on the design before deployment.

Answer the following questions:

- Identify at least three serious cryptographic weaknesses in this design.

- For each weakness, explain how an attacker could exploit it.

- Propose specific improvements or modern alternatives for each component.

- How do these flaws interact to make the system more vulnerable than the parts suggest?

- Why is secure integration just as important as secure algorithms?

Hints:

- Think about randomness, key reuse, padding oracles, hash collisions

- Think about system lifecycle: key rotation? certificate expiry?

- Consider what an attacker can replay, forge, or predict

- Evaluate the entire stack, not just the cipher

First, using the same key `K` for both AES-CBC encryption and HMAC violates key separation. An attacker who collects enough ciphertext-MAC pairs may mount forgery or chosen-ciphertext attacks, especially if padding oracles are present.

Second, generating IVs from the system time makes them predictable. If two messages are sent within the same second, they may reuse the IV. This breaks semantic security and potentially revealing patterns in the ciphertext.

Third, the use of SHA-1 for HMAC and RSA signatures is deprecated due to collision vulnerabilities. An attacker might craft multiple inputs with the same hash, potentially forging a signature or a MAC.

Fourth, the system does not check certificate revocation or expiry. Even if a key is compromised or a certificate is outdated, the device continues trusting it; opening the door to persistent attacks or firmware forgery.

These flaws reinforce each other: predictable IVs make ciphertext patterns visible; reused keys make forged ciphertexts more likely; and missing certificate checks allow the attacker to persist in the system once any part is compromised.

The system should use separate keys for encryption and MAC, switch to AES-GCM or ChaCha20-Poly1305 for AEAD, use cryptographically random IVs, migrate to SHA-256 or SHA-3, and implement revocation checking (e.g., OCSP or short-lived certs). Secure integration means applying each primitive correctly, and ensuring they work together under realistic threat models.

Patch the Handshake

This question is challenging. It requires knowledge from various domains of cybersecurity where you are given a scenario and are supposed to find cryptographic weakness in the design and then fix the broken protocol.

Background

Designing a secure protocol is difficult. Even if you use standard crypto primitives like RSA or AES, incorrect sequencing, missing authentication, or assumptions about trust can make the system vulnerable. Many real-world attacks exploit these flaws. Not broken algorithms, but broken glue.

Being able to spot and repair insecure protocols is a key skill in applied cryptography.

Scenario

Below is a simplified handshake protocol between a client and a server to establish a secure session key K_session:

- Client → Server:

Hello - Server → Client:

RSA_enc(K_session, Server_PublicKey) - Client and server both use

K_sessionfor AES encryption.

The goal is to establish a shared symmetric key using the server’s public RSA key. However, the protocol is vulnerable to several attacks. There’s no client authentication, no signature or certificate involved, and no proof that the server actually owns the private key.

Answer the following questions:

- Identify two major vulnerabilities in this protocol.

- How could a man-in-the-middle attacker exploit this exchange?

- Propose a revised handshake that defends against these attacks.

- Should the server sign anything? Should the client verify anything?

- How do TLS and SSH avoid these design mistakes?

Hints:

- Think about certificate validation, forward secrecy, and key confirmation

- Can you replace RSA with a modern key exchange like ECDHE?

- What happens if an attacker intercepts and rewrites the handshake?

One major vulnerability is the lack of server authentication. The client accepts any RSA public key without verifying its origin. A man-in-the-middle attacker can replace the server’s public key with their own and decrypt the session key.

A second issue is the lack of key confirmation. The client sends an encrypted session key and assumes the server received it, but there’s no handshake step where the server proves it possesses the private key or the session key.

An attacker could intercept the "Hello" message, substitute their own key, and forward the rest of the protocol as a proxy, fully decrypting and re-encrypting traffic. This is a textbook MITM attack.

To fix the protocol, the server should send an X.509 certificate signed by a trusted CA to prove its identity. The client should verify this certificate before encrypting anything. Even better, use an ephemeral key exchange (like ECDHE), with both parties contributing randomness, and include signatures to authenticate the exchange.

TLS uses signed ephemeral key exchanges and certificates to authenticate the server, with optional client authentication. SSH uses known host keys or certificates, and includes mutual key confirmation during setup. Both protocols defend against passive and active MITM attacks by authenticating all public parameters and confirming possession of private keys.

The Slippery Protocol

Background

A good cryptographic protocol should ensure confidentiality (no one else can read), integrity (no one can tamper undetected), and authentication (you know who you’re talking to). Many flawed designs violate one or more of these goals: not through broken ciphers, but due to bad assumptions or missing steps.

Understanding what each part of a protocol contributes, and which goal it secures, is essential.

Scenario

A custom-designed secure file transfer system uses this protocol:

- The client compresses a file.

- The client encrypts the file using AES-CBC with a pre-shared key

Kand a fixed IV of all zeroes. - The client sends the ciphertext and a SHA-256 hash of the plaintext file.

- The server decrypts the ciphertext and compares the hash to check for tampering.

Answer the following questions:

- Does this protocol guarantee confidentiality? Why or why not?

- Does it provide integrity? What weaknesses exist?

- Is authentication ensured between client and server?

- What are the specific technical flaws in this design?

- Propose improvements that enforce all three goals correctly.

Hints:

- Fixed IV + CBC → predictable ciphertexts

- SHA-256 is not a MAC

- Who proves they’re who they claim to be?

- How do modern protocols bundle encryption + integrity?

Confidentiality is weakened due to the use of a fixed IV in AES-CBC. If the same file is encrypted twice, the ciphertext will be identical. An attacker can detect file reuse or infer structural patterns, breaking semantic security.

Integrity is not properly enforced. A SHA-256 hash of the plaintext is not a secure message authentication code (MAC). An attacker can tamper with the ciphertext, and unless the tampered data results in the same hash post-decryption, the server won’t detect the change.

There is no authentication</strong. The server doesn’t verify the client’s identity, nor does the client verify the server. Anyone who knows the shared key `K` (or intercepts the file and hash) could send spoofed messages.

</p>

Specific technical flaws include the use of deterministic IVs, lack of keyed integrity checking</strong (no HMAC or AEAD), and absence of any identity verification mechanism such as certificates or digital signatures.

</p>

To fix this, use a modern AEAD scheme like AES-GCM or ChaCha20-Poly1305, which ensures both encryption and integrity in one operation. Replace SHA-256 with an HMAC if separate integrity is needed. To add authentication, include client and server certificates or signed tokens as part of the handshake. The IV should be randomly generated for each encryption session and transmitted safely.

50.005 CSE

50.005 CSE