- Checkoff and Lab Questionnaire

- Introduction: The Tiny OS

- Asynchronous Interrupts

- Synchronous Interrupts

- User Programs

- Part A: Add mouse interrupt handler

- Part B: Add Mouse() Supervisor Call

50.005 Computer System Engineering

Information Systems Technology and Design

Singapore University of Technology and Design

Natalie Agus (Summer 2025)

TinyOS IRQ handler and SVC Handler

In this lab, you are tasked to write an I/O interrupt handler (asynchronous interrupt) and an I/O supervisor call handler (synchronous interrupt) for a very simple OS called the TinyOS using the Beta assembly language that you have learned from 50002 last term. This is closely related to what we have learned last week regarding hardware interrupt and system call as part of Operating System services.

This lab is also closely related to your 50002 materials. In particular, the lecture notes on Virtual Machine, and Asynchronous handling of I/O Devices are closely related to this lab.

You will be using bsim from 50002, an MIT Simulator for the Beta ISA. Here are a few useful resources to refresh your memory:

Checkoff and Lab Questionnaire

You are required to finish the lab questionnaire on eDimension and complete two CHECKOFF during this session. Simply show that your bsim simulates the desirable checkoff outcome for Part A and Part B (binary grading, either you complete it or you don’t) of the lab. Read along to find out more.

There will be no makeup slot for checkoff for this lab. If you miss the class in Week 2 with no LOA, you get zero. If you have LOA, show it to our TAs and you can checkoff during the following Week’s Lab session or at the TA’s discretion.

Introduction: The Tiny OS

Enter the following to your terminal to clone the Tiny OS repository and open the directory.

git clone https://github.com/natalieagus/lab-tinyOS.git

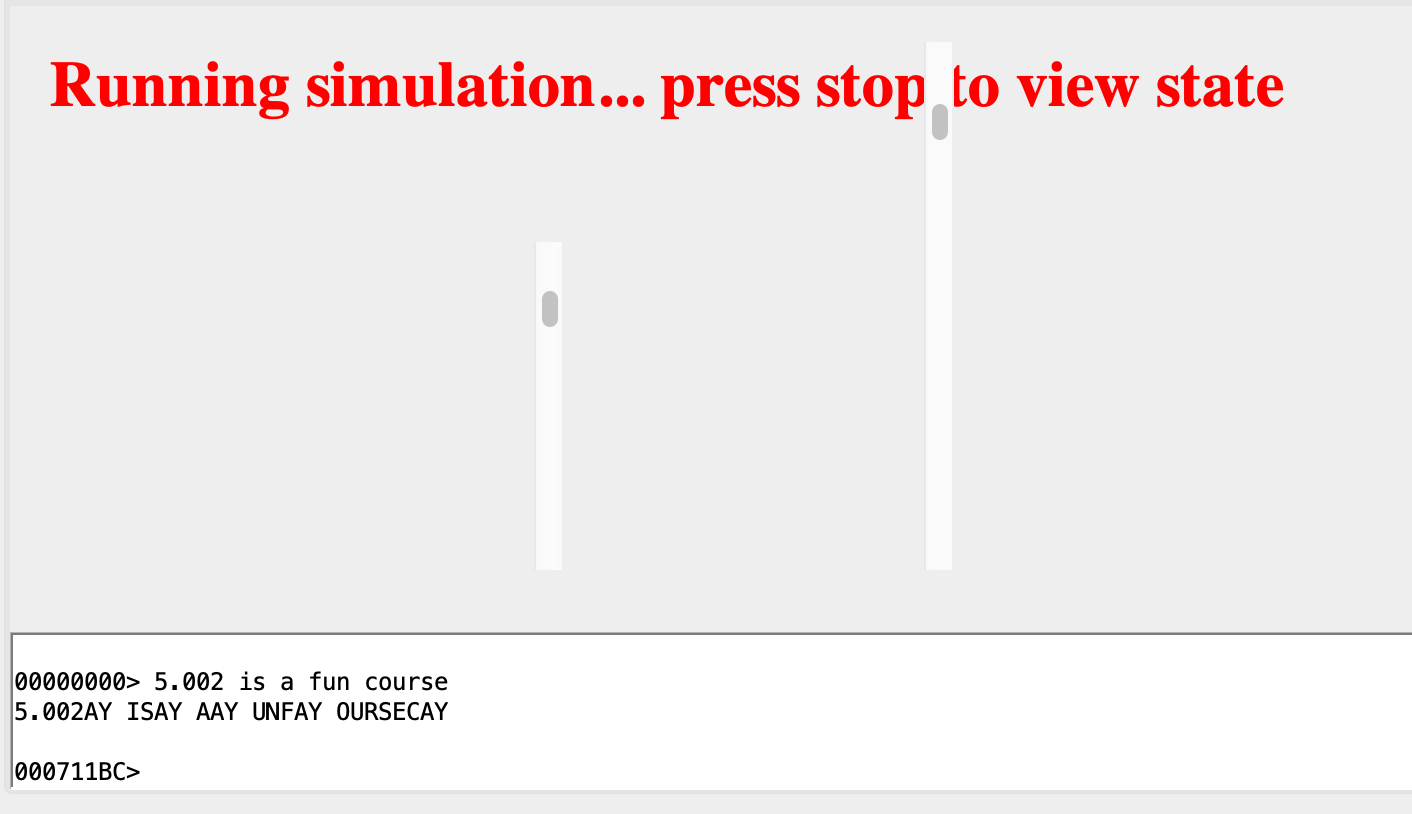

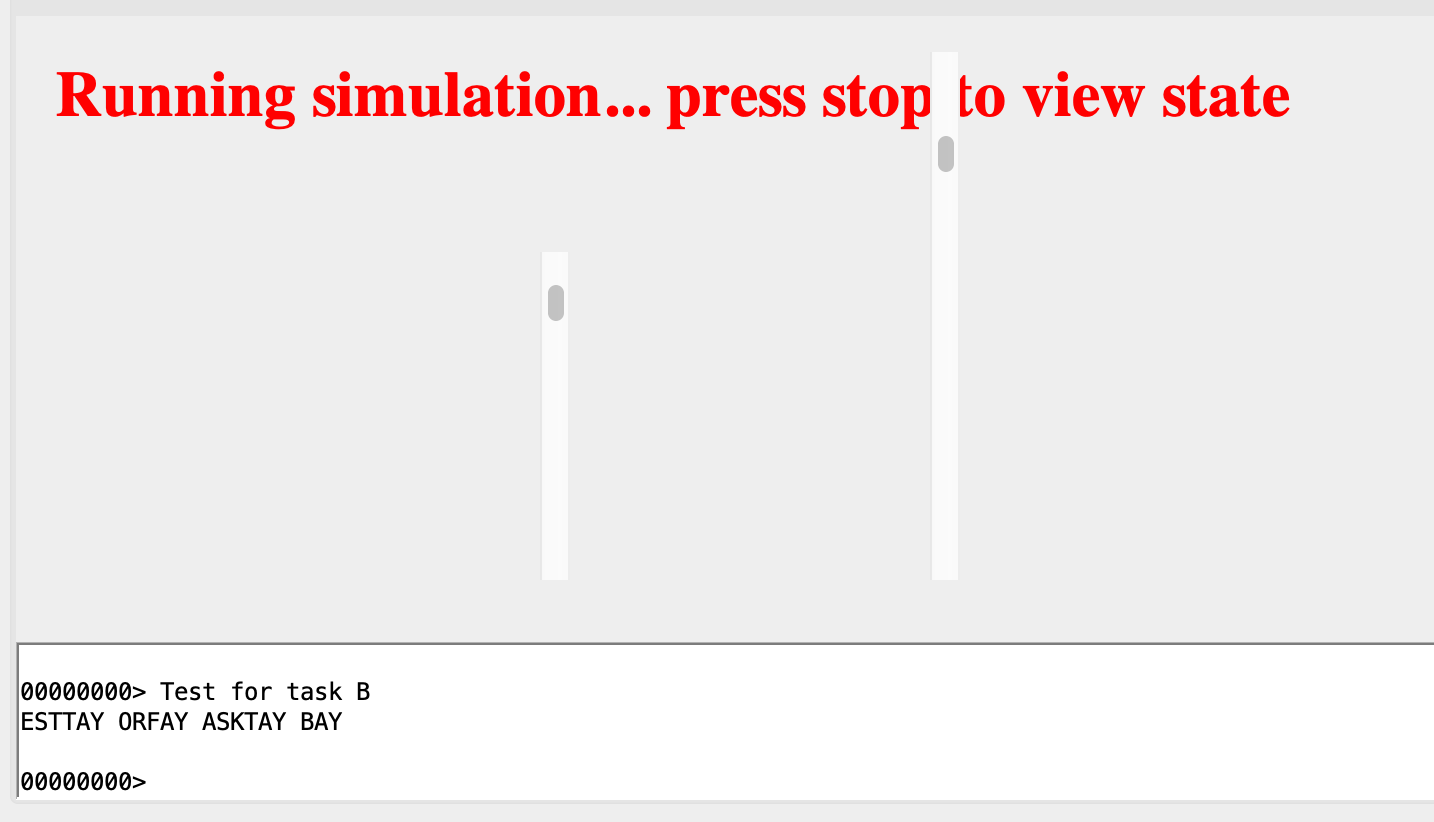

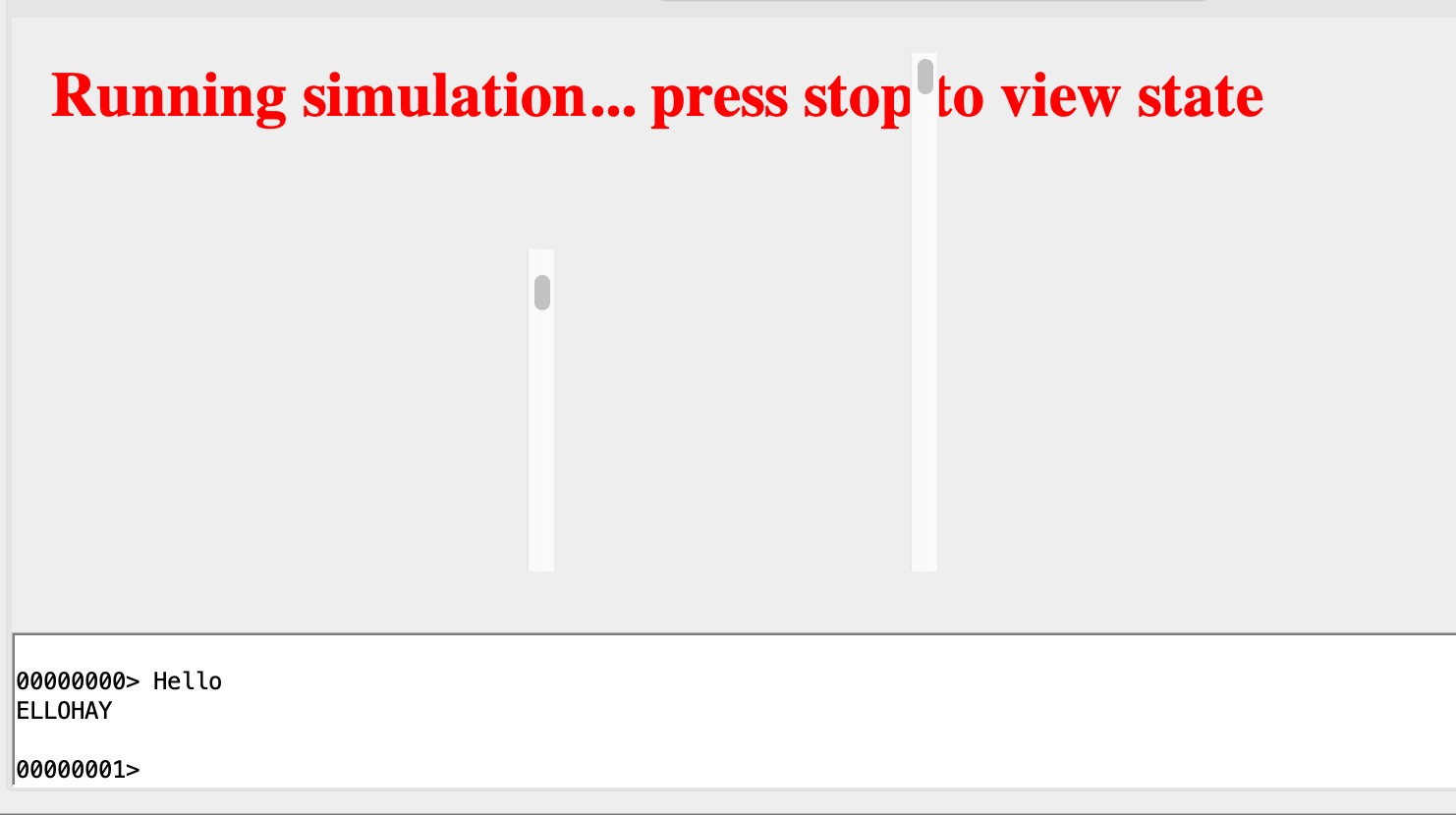

You will find a few files: bsim.jar, beta.uasm, tinyOS.uasm. You should know what the first two are from 50002 (yes, its the same Beta simulator we used before). tinyOS.uasm is a program that implements a minimal Kernel supporting a simple timesharing system. Use BSim to load this file, assemble, and then run tinyOS.uasm. The following prompt should appear in the console pane of the BSim Display Window:

As you type, each character is echoed to the console and when you hit return the whole sentence is translated into Pig Latin and written to the console:

The hex number 0x000711BC written out in the screenshot above as part of the prompt is a count of the number of times one of the user-mode processes (Process 2) has been scheduled while you typed in the sentence or leave the program idling.

This program implements a primitive OS kernel for the Beta along with three simple user-mode processes hooked together thru a semaphore-controlled bounded buffer. The three processes – and the kernel – share an address space; each is allocated its own stack (for a total of 4 stacks), and each process has its own virtual machine state (ie, registers). The latter is stored in the kernel ProcTbl, which contains a data structure for each process.

Before we start, it is useful to open beta.uasm and familiarise yourself with some convenient macros, namely:

.macro CALL(label) BR(label, LP)

.macro RTN() JMP(LP)

.macro XRTN() JMP(XP)

and privileged mode instructions to interact with the system I/O and other functionalities:

.macro PRIV_OP(FNCODE) betaopc (0x00, 0, FNCODE, 0)

.macro HALT() PRIV_OP (0)

.macro RDCHAR() PRIV_OP (1)

.macro WRCHAR() PRIV_OP (2)

.macro CYCLE() PRIV_OP (3)

.macro TIME() PRIV_OP (4)

.macro CLICK() PRIV_OP (5)

.macro RANDOM() PRIV_OP (6)

.macro SEED() PRIV_OP (7)

.macro SERVER() PRIV_OP (8)

For instance, WRCHAR() will print a single character to the terminal. this is implemented in Java (you can find it in MIT’s 6.004 bsim’s source code). Here’s a snippet of it:

switch (inst & 0xFFFF) { // look at the last 16 bits of the instruction

case 0: // halt

...

case 1: // rdchar: return char in regs[0] or loop

...

break dispatch;

case 2: // wrchar: print char in regs[0]

if (tty) {

usertty.append(String.valueOf((char) regs[0]));

try {

usertty.setCaretPosition(usertty.getText().length() - 1);

} catch (Exception e) {

}

Thread.yield();

} else

Trap(ILLOP);

break dispatch;

case 3: // cycle: return current cycle count in regs[0]

...

Supervisor Mode

All kernel code is executed with the Kernel-mode bit of the program counter – its highest-order bit (MSB) — set. This causes new interrupt requests to be deferred until the kernel returns to user mode.

Asynchronous Interrupts

tinyOS.uasm implements the following Interrupt Service Routine (ISR), also known as Interrupt Handlers to support Asynchronous Interrupts:

Vectored Interrupt Routine

Kernel-mode vector interrupt routine for handling input from the keyboard, clock, reset, and illegal instruction (trap).

||| Interrupt vectors:

. = VEC_RESET

BR(I_Reset) | on Reset (start-up)

. = VEC_II

BR(I_IllOp) | on Illegal Instruction (eg SVC)

. = VEC_CLK

BR(I_Clk) | On Clock interrupt

. = VEC_KBD

BR(I_Kbd) | on Keyboard interrupt

. = VEC_MOUSE

BR(I_BadInt) | on Mouse interrupt

Vectored interrupt is a method where the interrupt request (IRQ) directly points to the address of the Interrupt Handler (e.g: I_Reset, or I_Clk above) specific to that interrupt. This allows for faster processing compared to non-vectored interrupts, where the CPU may need to poll or search for the handler’s address.

An Interrupt Service Routine (ISR) or handler is a specialized function in an operating system or firmware that responds to interrupts by temporarily halting the main program flow to handle specific events or conditions. Triggered by hardware or software signals, ISRs manage tasks such as input from devices or timers, ensuring quick and efficient responses to immediate system needs.

Keyboard Interrupt Handling

A keyboard key press causes the asynchronous interrupt to occur, which results in the execution of a keyboard interrupt handler labelled I_Kbd. Incoming characters are stored in a kernel buffer called Key_State for subsequent use by user-mode programs.

Key_State: LONG(0) | 1-char keyboard buffer.

I_Kbd: ENTER_INTERRUPT() | Adjust the PC!

ST(r0, UserMState) | Save ONLY r0...

RDCHAR() | Read the character,

ST(r0,Key_State) | save its code.

LD(UserMState, r0) | restore r0, and

JMP(xp) | and return to the user.

Reset Handling

I_Reset:

CMOVE(P0Stack, SP)

CMOVE(P0Start, XP)

JMP(XP)

Upon startup, we will begin executing Process 0, which instruction address resides at address with label P0Start.

Clock Interrupt Handling

The clock interrupt invokes the scheduler asynchronously. Each compute-bound process gets a quantum consisting of TICS clock interrupts, where TICS is the number stored in the variable Tics below. To avoid overhead, we do a full state save only when the clock interrupt will cause a process swap, using the TicsLeft variable as a counter.

We do a LIMITED state save (R0 only) in order to free up a register, then reduce TicsLeft by 1. When it becomes negative, we do a FULL state save and call the scheduler; otherwise we just return, having burned only a few clock cycles on the interrupt. RECALL that the call to Scheduler sets TicsLeft to Tics, giving the newly-swapped-in process a full quantum.

Tics: LONG(2) | Number of clock interrupts/quantum.

TicsLeft: LONG(0) | Number of tics left in this quantum

I_Clk: ENTER_INTERRUPT() | Adjust the PC!

ST(r0, UserMState) | Save R0 ONLY, for now.

LD(TicsLeft, r0) | Count down TicsLeft

SUBC(r0,1,r0)

ST(r0, TicsLeft) | Now there's one left.

CMPLTC(r0, 0, r0) | If new value is negative, then

BT(r0, DoSwap) | swap processes.

LD(UserMState, r0) | Else restore r0, and

JMP(XP) | return to same user.

DoSwap: LD(UserMState, r0) | Restore r0, so we can do a

SAVESTATE() | FULL State save.

LD(KStack, SP) | Install kernel stack pointer.

CALL(Scheduler) | Swap it out!

BR(I_Rtn) | and return to next process.

Synchronous Interrupts

tinyOS.uasm implements a few functionalities to support Synchronous Interrupts (also known as trap or supervisor call). Kernel-mode supervisor call dispatching and a repertoire of call handlers that provide simple I/O services to user-mode programs include:

Halt()– stop a user-mode process (equivalent to closing or killing the process)WrMsg()– write a null-terminatedASCIIstring to the consoleWrCh()– write theASCIIcharacter found inR0to the consoleGetKey()– return the nextASCIIcharacter from the keyboard inR0; this call does not return to the user (blocks) until there is a character available.HexPrt()– convert the value passed in R0 to a hexadecimal string and output it to the console.Yield()– immediately schedule the next user-mode program for execution. Execution will resume in the usual fashion when the round-robin scheduler chooses this process again.

Implementing SVC Handlers

Supervisor calls (SVC) are invoked via specific illegal instructions that causes an ILLOP when executed. Any illegal instruction will cause the ILLOP handler to be executed, but there exist a specific illegal instruction (OPCODE 000001) that leads us to SVC instead:

I_IllOp:

SAVESTATE() | Save the machine state.

LD(KStack, SP) | Install kernel stack pointer.

LD(XP, -4, r0) | Fetch the illegal instruction

SHRC(r0, 26, r0) | Extract the 6-bit OPCODE, SVC opcode is 000001 (second element of the table)

SHLC(r0, 2, r0) | Make it a WORD (4-byte) index

LD(r0, UUOTbl, r0) | Fetch UUOTbl[OPCODE]

JMP(r0) | and dispatch to the UUO handler.

.macro UUO(ADR) LONG(ADR+PC_SUPERVISOR) | Auxiliary Macros

.macro BAD() UUO(UUOError)

UUOTbl: BAD() UUO(SVC_UUO) BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

BAD() BAD() BAD() BAD()

....

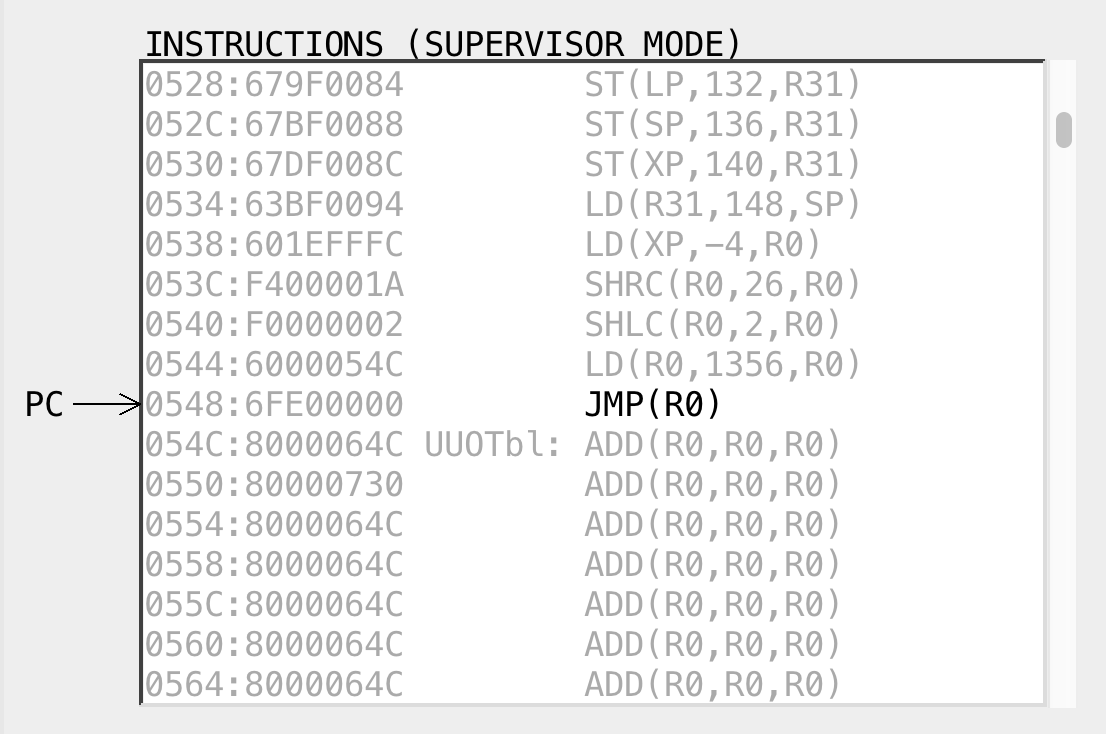

The kernel code should reside in the memory region with MSB of 1, as per Beta’s way of setting Kernel mode if our address space spans 32 bits. However, note that BSim memory is not actually 4GB in size. The UUOTbl actually resides in address 0x054C:

To work around this, we use the macro:

.macro UUO(ADR) LONG(ADR+PC_SUPERVISOR) | Auxiliary Macros

This simply adds MSB of 1 in the content of the UUOTbl, which makes the PC to be in Supervisor mode when we execute JMP(r0) to dispatch the UUO handler.

The illegal instruction trap handler looks for illegal instructions it knows to be supervisor calls and calls the appropriate handler defined in SVC_UUO, which makes use of the SVC_Tbl to branch to the appropriate trap handler based on the service call being made:

SVC_UUO:

LD(XP, -4, r0) | The faulting instruction.

ANDC(r0,0x7,r0) | Pick out low bits,

SHLC(r0,2,r0) | make a word index,

LD(r0,SVCTbl,r0) | and fetch the table entry.

JMP(r0)

SVCTbl: UUO(HaltH) | SVC(0): User-mode HALT instruction

UUO(WrMsgH) | SVC(1): Write message

UUO(WrChH) | SVC(2): Write Character

UUO(GetKeyH) | SVC(3): Get Key

UUO(HexPrtH) | SVC(4): Hex Print

UUO(WaitH) | SVC(5): Wait(S) ,,, S in R3

UUO(SignalH) | SVC(6): Signal(S), S in R3

UUO(YieldH) | SVC(7): Yield()

The translation between SVC(0) to Halt(), SVC(1) to WrMsg() and so on is declared as macros to interface with the Kernel code.

||| Definitions of macros used to interface with Kernel code:

.macro Halt() SVC(0) | Stop a process.

.macro WrMsg() SVC(1) | Write the 0-terminated msg following SVC

.macro WrCh() SVC(2) | Write a character whose code is in R0

.macro GetKey() SVC(3) | Read a key from the keyboard into R0

.macro HexPrt() SVC(4) | Hex Print the value in R0.

.macro Yield() SVC(7) | Give up remaining quantum

Note that this is just for convenience. The macro declarations are made so that we can conveniently write Halt() as part of our instruction instead of the more unintuitive version of it, e.g: SVC(0).

The SVC Handler is the specific part of the operating system or kernel that responds to the SVC instruction. When an SVC instruction is executed, the processor switches to a privileged mode and begins execution of the SVC Handler. This handler is responsible for interpreting the request made by the SVC instruction (often by examining the argument or system call number provided with the SVC), carrying out the requested operation, and then returning control back to the user-space application, often with some result.

The next few sections contain explanations about each of the handlers that are already implemented for you.

Halt Handler

The Halt() handler is implemented as follows:

HaltH: BR(I_Wait) | SVC(0): User-mode HALT SVC

It pauses the current execution of the calling process, then forces the CPU to execute I_Wait, which contains a routine to call the scheduler and therefore schedule other processes (if it exists). You will learn more about process scheduling in the weeks to come.

Write Message and Write Char Handler

The WrMsg() is equivalent to a regular print statement. Its purpose is to print a 0-terminated message. We can define a string immediately following the WrMsg() instruction. Execution resumes with the instruction following the string as such:

WrMsg()

.text “This text is sent to the console…\n”

* …next instruction…

The handler is implemented as follows:

WrMsgH: LD(UserMState+(4*30), r0) | Fetch interrupted XP, then

CALL(KMsgAux) | print text following SVC.

ST(r0,UserMState+(4*30)) | Store updated XP.

BR(I_Rtn)

It calls an Auxiliary routine for sending message to the console. This routine must be called while in supervisor mode. On entry, R0 should point to data; on return, R0 holds next longword aligned location after data.

KMsgAux:

PUSH(r1)

PUSH(r2)

PUSH(r3)

PUSH(r4)

MOVE (R0, R1)

WrWord: LD (R1, 0, R2) | Fetch a 4-byte word into R2

ADDC (R1, 4, R1) | Increment word pointer

CMOVE(4,r3) | Byte/word counter

WrByte: ANDC(r2, 0x7F, r0) | Grab next byte -- LOW end first!

BEQ(r0, WrEnd) | Zero byte means end of text.

WRCHAR() | Print it.

SRAC(r2,8,r2) | Shift out this byte

SUBC(r3,1,r3) | Count down... done with this word?

BNE(r3,WrByte) | Nope, continue.

BR(WrWord) | Yup, on to next.

WrEnd:

MOVE (R1, R0)

POP(r4)

POP(r3)

POP(r2)

POP(r1)

RTN()

When the routine returns back to WrMsgH(), it will return to the calling user process and resume its execution.

WrChH() works similarly, but in this case we just print out 1 character that we have put in R0 so we don’t have to go through the whole ordeal of “loading a string” from the regs to be printed on screen.

WrChH: LD(UserMState,r0) | The user's <R0>

WRCHAR() | Write out the character,

BR(I_Rtn) | then return

GetKey Handler

The purpose of this handler is to read a single keystroke from the Key_State, a dedicated space in the Kernel to hold the current keystroke into R0 so that the calling user process can use it.

Key_State: LONG(0) | 1-char keyboard buffer.

GetKeyH: | return key code in r0, or block

LD(Key_State, r0)

BEQ(r0, I_Wait) | on 0, just wait a while

| key ready, return it and clear the key buffer

LD(Key_State, r0) | Fetch character to return

ST(r0,UserMState) | return it in R0.

ST(r31, Key_State) | Clear kbd buffer

BR(I_Rtn) | and return to user.

HexPrt Handler

Similar to WrCh(), we print the value placed in R0 in hex form (instead of char form).

HexPrtH:

LD(UserMState,r0) | Load user R0

CALL(KHexPrt) | Print it out

BR(I_Rtn) | And return to user

KHexPrt is a hex print procedure defined as follows. It goes through the 32-bit word stored at R0, and process it nybble (half a byte) by nybble.

HexDig: LONG('0') LONG('1') LONG('2') LONG('3') LONG('4') LONG('5')

LONG('6') LONG('7') LONG('8') LONG('9') LONG('A') LONG('B')

LONG('C') LONG('D') LONG('E') LONG('F')

KHexPrt:

PUSH(r0) | Saves all regs, incl r0

PUSH(r1)

PUSH(r2)

PUSH(lp)

CMOVE(8, r2)

MOVE(r0,r1)

KHexPr1:

SRAC(r1,28,r0) | Extract digit into r0.

MULC(r1, 16, r1) | Next loop, next nybble...

ANDC(r0, 0xF, r0)

MULC(r0, 4, r0)

LD(r0, HexDig, r0)

WRCHAR ()

SUBC(r2,1,r2)

BNE(r2,KHexPr1)

POP(lp)

POP(r2)

POP(r1)

POP(r0)

RTN()

Yield Handler

Finally, a Yield() is called when a user process wants to give up the remaining quanta so that other process can be scheduled.

YieldH: CALL(Scheduler) | Schedule next process, and

BR(I_Rtn) | and return to user.

Processes are given equal time slices called quanta (or quantums) takes turns of one quantum each. if a process finishes early, before its quantum expires, the next process starts immediately and gets a full quantum.

User Programs

tinyOS.uasm also contains code for three user programs named P0, P1, and P2. They’re located towards the end of tinyOS.uasm. We will not dive in too deep about who each user programs is scheduled (that will be for another lab). For now, here’s all the information you need:

P0: Prompts the user for new lines of input and store the inputP1: Converts the given input into piglatin and printing it back to the terminalP2: Increments an internal counter andYield(). Thanks toP2, you can see some numbers printed at the prompt

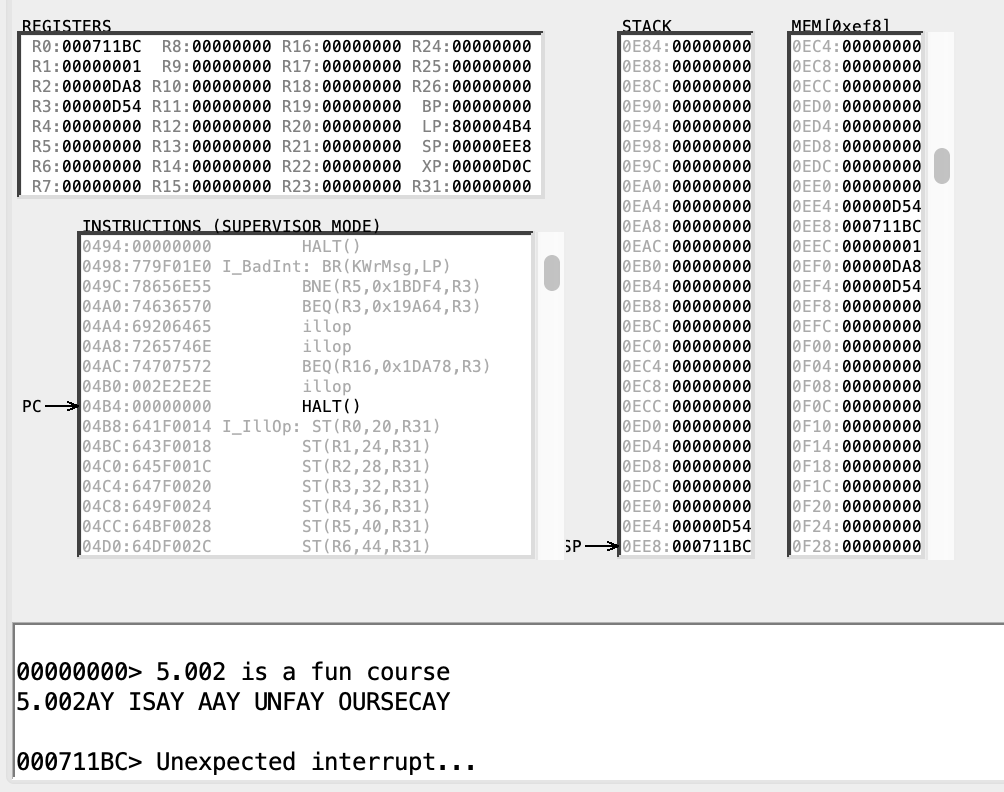

Now that we understand how TinyOS works, we can implement two things for this lab: a mouse interrupt handler and a mouse supervisor call.

Part A: Add mouse interrupt handler

When you click the mouse over the console pane, BSim generates an interrupt, forcing the PC to 0x80000010 (remember the interrupt vector?) and saving PC+4 of the interrupted instruction in the XP register. We paste the interrupt vector here again for your reference. Interrupt vector is hardwired in the CPU:

. = VEC_RESET | This is loaded at address 0x80000000

BR(I_Reset) | on Reset (start-up)

. = VEC_II | This is loaded at address 0x80000004

BR(I_IllOp) | on Illegal Instruction (eg SVC)

. = VEC_CLK | This is loaded at address 0x80000008

BR(I_Clk) | On clock interrupt

. = VEC_KBD | This is loaded at address 0x8000000C

BR(I_Kbd) | on Keyboard interrupt

. = VEC_MOUSE | This is loaded at address 0x80000010

BR(I_BadInt) | on mouse interrupt

The Beta itself implements a vectored interrupt scheme where different types of interrupts force the PC to different addresses (rather than having all interrupts for the PC to 0x80000008 and query each I/O device for input fetch). The following table shows how different interrupt events are mapped to PC values (PCSEL is wired to set PC to be these values depending on the triggering interrupt):

0x80000000 reset

0x80000004 illegal opcode

0x80000008 clock interrupt (must specify “.options clk” to enable)

0x8000000C keyboard interrupt (must specify “.options tty” to enable)

0x80000010 mouse interrupt (must specify “.options tty” to enable)

The original tinyOS.uasm prints out “Illegal interrupt” and then halts if a mouse interrupt is received:

Change this behavior by:

- Adding an interrupt handler that stores the click information in a new kernel memory location and then,

- Returns to the interrupted process.

You might find the keyboard interrupt handler I_Kbd a good model to follow. Also, you might find this bsim documentation and beta isa documentation handy.

The CLICK() instruction

For this Lab, there exist a special Beta instruction your interrupt handler can use to retrieve information (coordinates of click) about the last mouse click: CLICK(). This instruction can only be executed when in kernel mode (e.g., from inside the mouse click interrupt handler).

It automatically returns a value in R0: -1 if there has not been a mouse click since the last time CLICK() was executed, or a 32-bit integer.

The integer is formatted as follows:

- The

Xcoordinate of the click in the high-order 16 bits of the word, and - The

Ycoordinate of the click in the low-order 16 bits.

The coordinates are non-negative and relative to the upper left hand corner of the console pane. In our scenario, CLICK() should only be called AFTER a mouse click interrupt occur, so we should never see -1 as a return value.

Further Notes about CLICK()

An instruction involving hardware access like CLICK() is a specialized operation. In real-world systems, this interaction typically involves reading from a device register or memory-mapped I/O location, not necessarily as simple as this CLICK() instruction. Special instructions for interacting with hardware devices are usually implemented as part of the instruction set architecture (ISA) and, by extension, the CPU’s datapath.

In x86 architecture, there exist IN and OUT (or similar) instructions to transfer data between a specific I/O device and a CPU register. The IN instruction reads data from an I/O device into a CPU register, while the OUT instruction writes data from a CPU register to an I/O device.

In RISC architecture, they typically have MMIO (Memory-Mapped I/O), akin to our lab (Lab 4 Part 2) in 50002. Instead of distinct IN/OUT instructions, some architectures use memory-mapped I/O, where I/O device registers are mapped to specific memory addresses. Reading from or writing to these addresses allows for I/O operations. This isn’t a “special instruction” per se but utilizes standard memory access instructions in a special context.

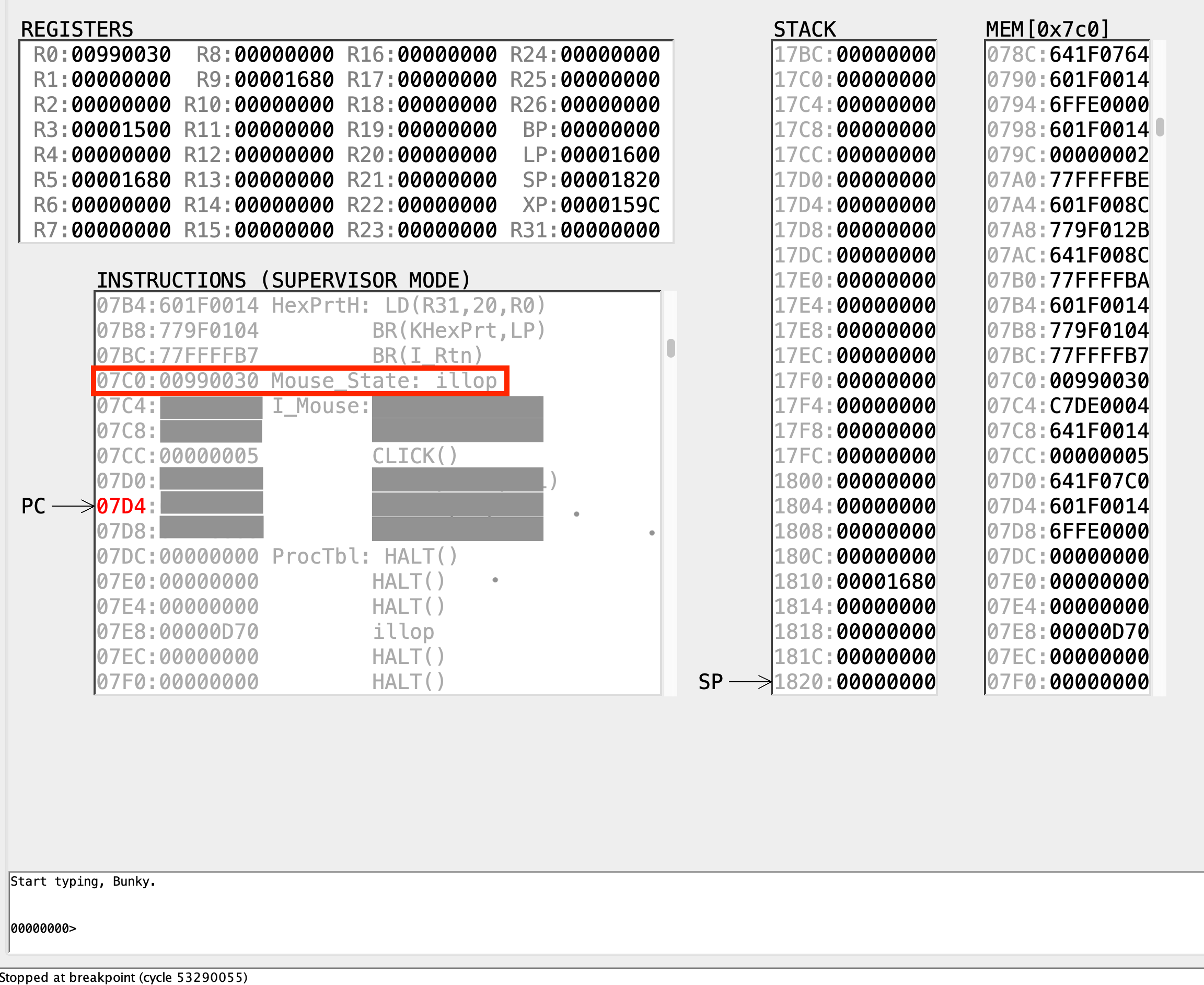

Testing Your Implementation with .breakpoint

Insert a .breakpoint instruction right before the JMP(XP) at the end of your mouse interrupt handler, run the program and click the mouse over the console pane.

If things are working correctly the simulation should stop at the breakpoint and you can examine the kernel memory location where the mouse info was stored to verify that it is correct. In the sample below, we name the memory location as Mouse_State, and the value in the red box signifies the coordinates of the mouse click made in the console pane.

Task 1

CHECKOFF: Continuing execution (click the “Run” button in the toolbar at the top of the window) should return to the interrupted program. Demonstrate the above result to your instructor / TA in class. When you’re done remember to remove the breakpoint.

Part B: Add Mouse() Supervisor Call

This is the second part of your lab, which is to implement a trap handler for the user process to access last mouse click.

Now our job is to retrieve the mouse click coordinates that is stored in the Kernel variable Mouse_State in the sample screenshot above. Implement a Mouse() supervisor call that returns the coordinate information from the most recent mouse click (i.e., the information stored by the mouse interrupt handler).

Like GetKey() supervisor call to retrieve keyboard press, a user-mode call to Mouse() should consume the available click information. If no mouse click has occurred since the previous call to Mouse(), the supervisor call should “hang” (blocks execution) until new click information is available.

Blocking Execution

A blocking supervisor call means that the supervisor call should back up the calling process’ context and move on to schedule other processes if there’s no mouse click (branch to the scheduler to run some other user-mode program). It also adjust the calling process’ PC so that the next user-mode instruction to be re-executed is the Mouse() call.

Thus when the calling program is rescheduled for execution at some later point, the Mouse() call is re-executed and the whole process repeated again (checking whether there’s any recent mouse click). The calling process can only resume when there’s a mouse click.

From the user’s point of view, the Mouse() call completes its execution only when there is new click information to be returned.

The GetKey() supervisor call is a good model to follow.

Defining an SVC Macro

To define a new supervisor call Mouse(), add the following definition just after the definition for .macro Yield() SVC(7):

.macro Mouse() SVC(8)

This is the ninth supervisor call and the current code at SVC_UUO was tailored for processing exactly eight supervisor calls, so you’ll need to make the appropriate modifications to SVC_UUO instructions:

||| Sub-handler for SVCs, called from I_IllOp on SVC opcode:

SVC_UUO:

LD(XP, -4, r0) | The faulting instruction.

ANDC(r0,0x7,r0) | Pick out low bits, should you modify this to support more supervisor calls?

SHLC(r0,2,r0) | make a word index,

LD(r0,SVCTbl,r0) | and fetch the table entry.

JMP(r0)

You also need to modify the SVCTbl to now account for 9 supervisor calls instead of 8.

Testing Your Implementation

Once your Mouse() implementation is complete, add a Mouse() instruction just after P2Start. If things are working correctly, this user-mode process should now hang and Count3 should not be incremented even if you type in several sentences (i.e., the prompt should always be 00000000>).

Now click the mouse once over the console pane and then type more sentences. The prompt should read 00000001>

Task 2

CHECKOFF: Demonstrate the above result to your instructor / TA in class. When you are done, remember to remove the Mouse() instruction you added.

Note that if you implement empty mouse buffer as LONG(0), a click at valid coordinate 0,0 in the top left hand corner of the console will not be registered a valid mouse click, so you can’t just wholesale copy the the GetKey() supervisor model. Please consider this in your implementation, a suggested way is to use LONG(-1) to indicate an empty mouse buffer.

Summary

Congratulations 🍾, you have sucessfully implemented both asycnhronous and synchronous interrupt handlers for Mouse-related event.

Once you’ve get your checkoff, please save your work. We will need it in Lab 4.

50.005 CSE

50.005 CSE