Processes executing concurrently in the operating system may be either independent processes or cooperating processes:

- By default, processes are independent and isolated from one another (runs on its own virtual machine)

- A process is cooperating if it can affect or be affected by the other processes executing in the system.

Processes need to cooperate due to the following possible reasons:

- Information sharing

- Speeding up computations

- Modularity (protect each segments) and convenience

Cooperating processes require Interprocess Communication (IPC) mechanisms – these mechanisms are provided by or supported by the kernel. There are two ways to perform IPC:

- Shared Memory

- Message Passing (e.g: sockets)

POSIX Shared Memory

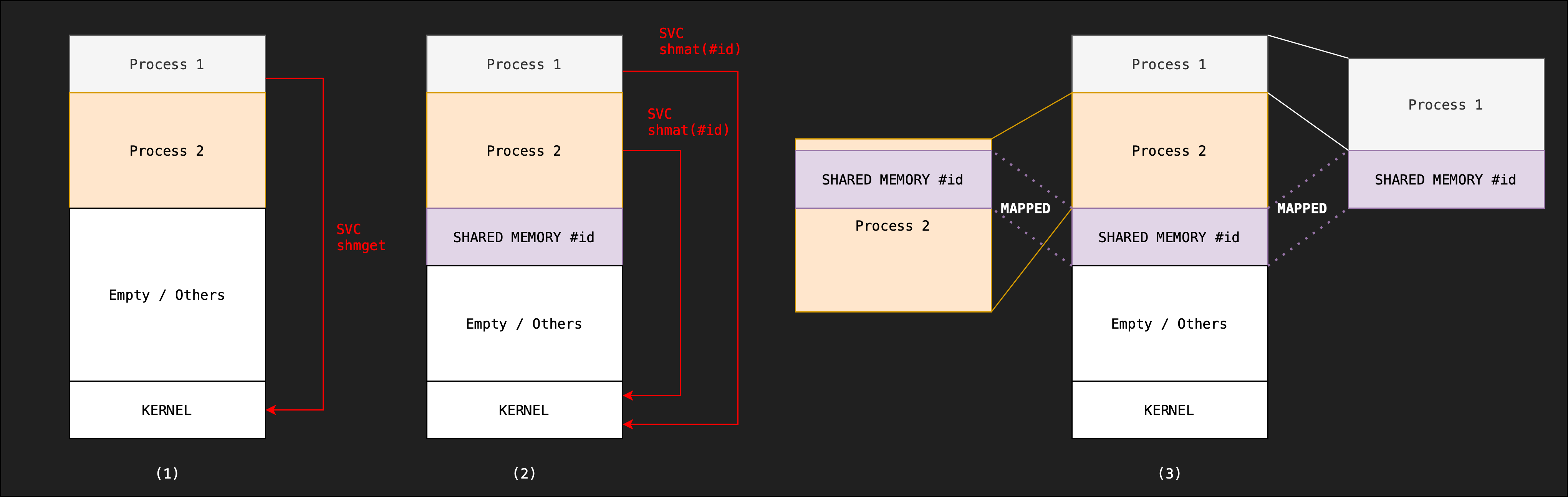

Shared memory is a region in the RAM that can be created and shared among multiple processes using system call.

- Kernel allocates and establishes a region of memory and return to the caller process.

- Once shared memory is established, all accesses are treated as routine user memory accesses for writing or reading to or from it, and no assistance from the kernel is required.

Procedure

This section is here to enhance your understanding. You can skip this if you want.

Both reader and writer get the shared memory identifier (an integer) using system call shmget. SHM_KEY is an integer that has to be unique, so any program can access what is inside the shared memory if they know the SHM_KEY. The Kernel will return the memory identifier associated with SHM_KEY if it is already created, or create it when it has yet to exist. The second argument: 1024, is the size (in bytes) of the shared memory.

int shmid = shmget(SHM_KEY, 1024, 0666 | IPC_CREAT);

Then, both reader and writer should attach the shared memory onto its address space (i.e: map the allocated segment in physical memory to the VM space of the calling process). You can type cast the return of shmat onto any data type you want. In essence, shmat returns an address of your address space that translates to the shared memory block1.

char *str = (char*) shmat(shmid, (void*)0, 0);

Afterwards, writer can write to the shared memory:

sprintf(str, "Hello world \n");

Reader can read from the shared memory:

printf("Data read from memory: %s\n", str);

The figure below illustrates the steps above:

Once both processes no longer need to communicate, they can detach the shared memory from their address space:

shmdt(str);

Finally, one of the processes can destroy it, typically the reader because it is the last process that uses it.

shmctl(shmid, IPC_RMID, NULL);

Of course one obvious issue that might happen here is that BOTH writer and reader are accessing the shared memory concurrently, therefore we will run into synchronisation problems whereby writer overwrites before reader finished reading or reader attempts to read an empty memory value before writer finished writing.

We will address such synchronisation problems in the next chapter.

Program: IPC without SVC?

Will the value of shared_int and shared_float be the same in the parent and child process?

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main(int argc, char const *argv[])

{

pid_t pid;

int shared_int = 10;

static float shared_float = 25.5;

pid = fork();

if (pid < 0)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Fork has failed. Exiting now");

return 1; // exit error

}

else if (pid == 0)

{

shared_int++;

printf("shared_int in child process: %d\n", shared_int);

shared_float = shared_float + 3;

printf("shared_float in child process: %f\n", shared_float);

}

else

{

printf("shared_int in parent process: %d\n", shared_int);

printf("shared_float in parent process: %f\n", shared_float);

wait(NULL);

printf("Child has exited.\n");

}

return 0;

}

Program: IPC with Shared Memory (unsync)

Parent and child processes can share the same segment, but we are faced with a synchronization problem, something called “race condition” (next week’s material).

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/ipc.h>

#include <sys/shm.h>

int main(int argc, char const *argv[])

{

pid_t pid;

int *ShmPTR;

int ShmID;

/**

This process asks for a shared memory of 4 bytes (size of 1 int) and attaches this

shared memory segment to its address space.

**/

ShmID = shmget(IPC_PRIVATE, 1 * sizeof(int), IPC_CREAT | 0666);

if (ShmID < 0)

{

printf("* shmget error (server) *\n");

exit(1);

}

/**

SHMAT attach the shared memory to the process

This code is called before fork() so both parent

and child processes have attached to this shared memory.

Pointer ShmPTR contains the address to the shared memory segment.

**/

ShmPTR = (int *)shmat(ShmID, NULL, 0);

if ((int)ShmPTR == -1)

{

printf("* shmat error (server) *\n");

exit(1);

}

printf("Parent process has created a shared memory segment.\n");

pid = fork();

if (pid < 0)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Fork has failed. Exiting now");

return 1; // exit error

}

else if (pid == 0)

{

*ShmPTR = *ShmPTR + 1; // dereference ShmPTR and increase its value

printf("shared_int in child process: %d\n", *ShmPTR);

}

else

{

printf("shared_int in parent process: %d\n", *ShmPTR); // race condition

wait(NULL); // move this above the print statement to see the change in ShmPTR value

printf("Child has exited.\n");

}

return 0;

}

Removing Shared Memory

In the code above, we didn’t detach and remove the shared memory, so it still persists in the system. Run the command ipcs -m to view it. To remove it, run the command ipcrm -m [mem_id]

Message Passing

Message passing is a mechanism to allow processes to communicate and to synchronize their actions without sharing the same address space. Every message passed back and forth between writer and reader (server and client) through message passing must be done using kernel’s help.

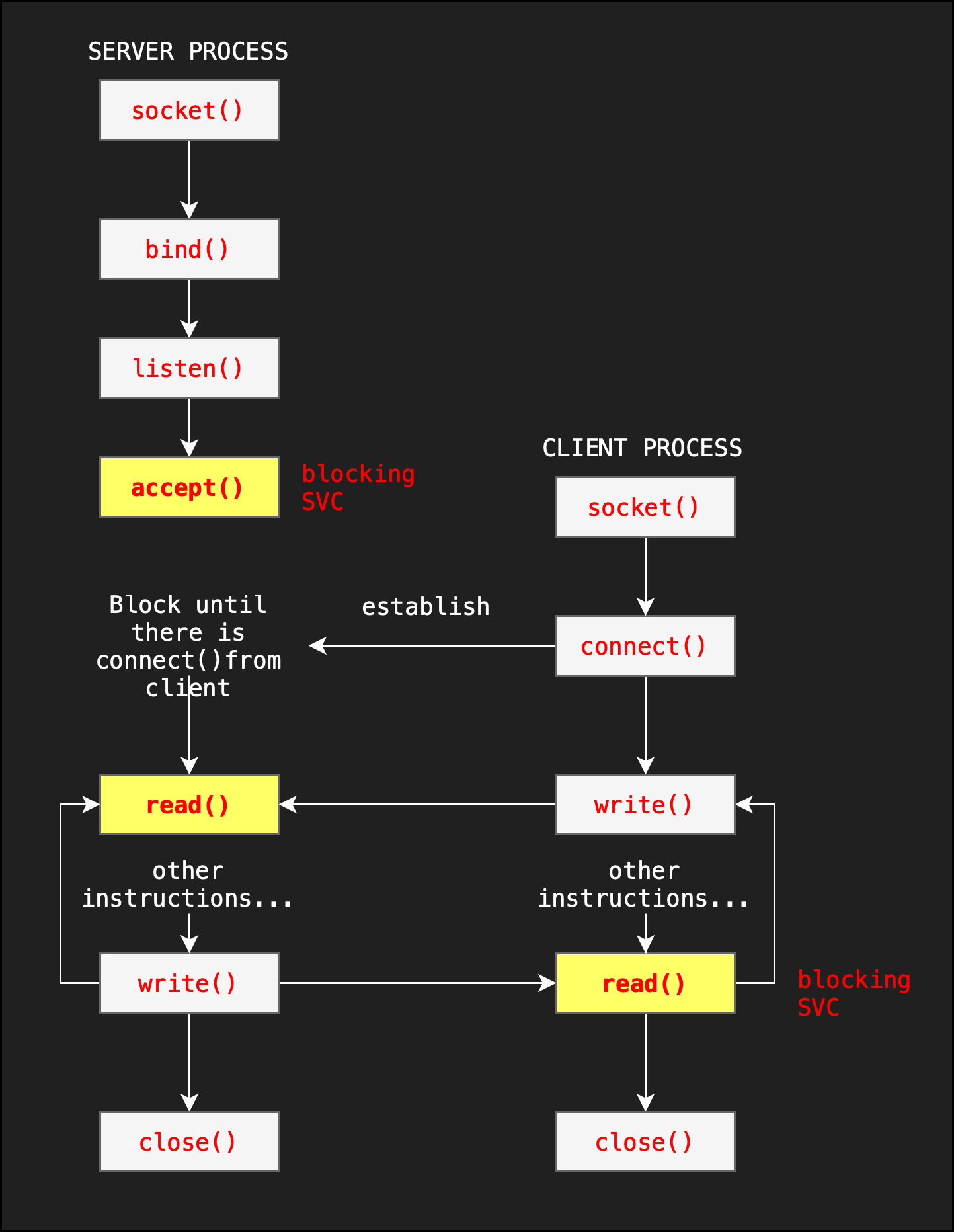

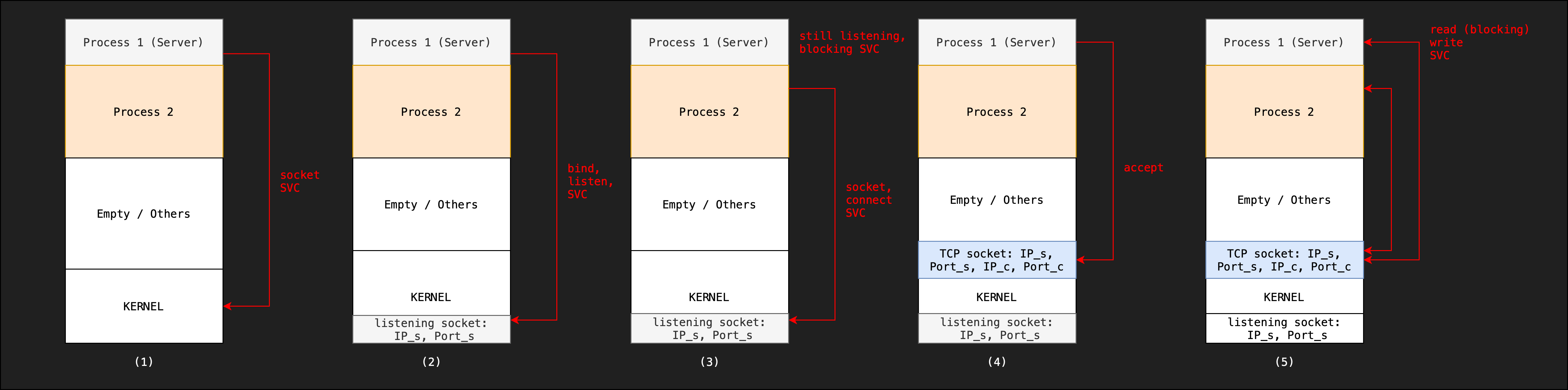

Socket

Socket is one of message passing interfaces.

A socket is one endpoint of a two-way communication link between two programs running on the network with the help of the kernel:

- It is a concatenation of an IP address, e.g: 127.0.0.1 for localhost

- And TCP (connection-oriented) or UDP (connectionless) port, e.g: 8080.

- We will learn more about UDP and TCP as network communication protocols in the later part of the semester.

- When concatenated together, they form a socket, e.g: 127.0.0.1:8080

- All socket connection between two communicating processes must be unique.

For processes in the same machine as shown in the figure above, both processes communicate through a socket with IP localhost and a unique, unused port number. Processes can read()or send()data through the socket through system calls:

- For example, when P1 tries to send a message (data) to P2 using socket, it has to copy the message from its own space to the kernel space first through the socket via

writesystem call. - Then, when P2 tries to read from the socket, that message in the kernel space is copied again to P2’s space via

readsystem call.

The diagram below illustrates how socket works in general:

Program: IPC using Socket

One process has to create a socket and listens for incoming connection. We call this process the server. After a listening socket is created, another process can connect to it. We call this process the client.

Server process has to be run first, followed by the client process. The code below implements both versions: blocking and non blocking read(). Try blocking version, then nonblocking.

Server program:

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h> /* Added for the nonblocking socket */

#define PORT 12345

int main(int argc, char const *argv[])

{

int server_fd, new_socket, valread;

int opt = 1;

struct sockaddr_in address;

int addrlen = sizeof(address);

char buffer[1024] = {0};

char *message = "Hello from server";

// Creating socket, and obtain the file descriptor

// Option:

// - SOCK_STREAM (TCP -- Week 11)

// - AF_INET (IPv4 Protocol -- Week 11)

if ((server_fd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0)) == 0)

{

perror("socket failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Attaching socket to port 12345

if (setsockopt(server_fd, SOL_SOCKET, SO_REUSEPORT,

&opt, sizeof(opt)))

{

perror("setsockopt");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

address.sin_family = AF_INET;

address.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

address.sin_port = htons(PORT);

// Assign name to the socket

/**

When a socket is created with socket(2), it exists in a name

space (address family) but has no address assigned to it. bind()

assigns the address specified by addr to the socket referred to

by the file descriptor sockfd. addrlen specifies the size, in

bytes, of the address structure pointed to by addr.

Traditionally, this operation is called "assigning a name to a

socket".

**/

if (bind(server_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&address,

sizeof(address)) < 0)

{

perror("bind failed");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// server listens for new connection (blocking system call)

if (listen(server_fd, 3) < 0)

{

perror("listen");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// accept incoming connection, creating a 1-to-1 socket connection with this client

if ((new_socket = accept(server_fd, (struct sockaddr *)&address,

(socklen_t *)&addrlen)) < 0)

{

perror("accept");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Choose between blocking and nonblocking read

// Blocking read

valread = read(new_socket, buffer, 1024);

// Nonblocking read

// fcntl(new_socket, F_SETFL, O_NONBLOCK); /* Change the socket into non-blocking state */

// valread = recv(new_socket, buffer, 1024, 0);

printf("%s\n", buffer);

send(new_socket, message, strlen(message), 0);

printf("Hello message sent to client\n");

return 0;

}

Client program:

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h> /* Added for the nonblocking socket */

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#define PORT 12345

int main(int argc, char const *argv[])

{

struct sockaddr_in address;

int sock = 0, valread;

struct sockaddr_in serv_addr;

char *message = "Hello from client";

char buffer[1024] = {0};

// create a socket

if ((sock = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0)) < 0)

{

printf("\n Socket creation error \n");

return -1;

}

// fill block of memory 'serv_addr' with 0

memset(&serv_addr, '0', sizeof(serv_addr));

// setup server address

serv_addr.sin_family = AF_INET;

serv_addr.sin_port = htons(PORT);

// Convert IPv4 addresses from text to binary form and store it at serv_addr.sin_addr

if (inet_pton(AF_INET, "127.0.0.1", &serv_addr.sin_addr) <= 0)

{

printf("\nInvalid address/ Address not supported \n");

return -1;

}

// connect to the socket with defined serv_addr setting

if (connect(sock, (struct sockaddr *)&serv_addr, sizeof(serv_addr)) < 0)

{

printf("\nConnection Failed \n");

return -1;

}

// send some data over

send(sock, message, strlen(message), 0);

printf("Hello message sent to server\n");

// read from server back

valread = read(sock, buffer, 1024);

printf("%s\n", buffer);

return 0;

}

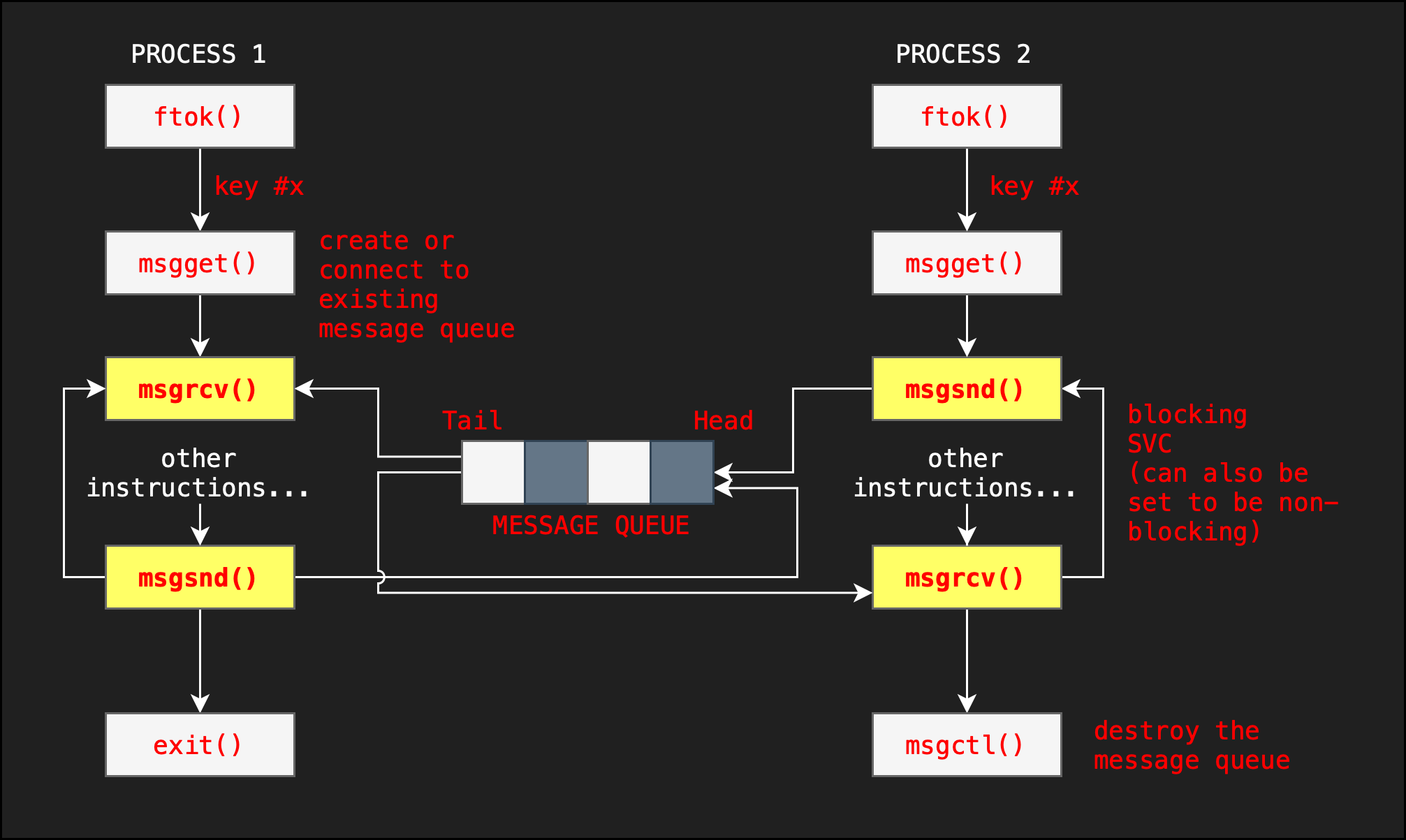

Message Queue

Message Queue is just another interface for message passing (another example being socket as shown in the previous section). It uses system call ftok, msgget, msgsnd, msgrcv each time data has to be passed between the processes. msgrcv and msgsnd can be made blocking or non blocking depending on the setup.

The figure below illustrates the general idea of Message Queue. The queue data structure is maintain by the Kernel, and processes may write into the queue at any time. If there are more than 1 writer and 1 reader at any instant, careful planning has to be made to ensure that the right message is obtained by the right process.

Writer process program:

// C Program for Message Queue (Writer Process)

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/ipc.h>

#include <sys/msg.h>

#define MAX 10

// structure for message queue

struct mesg_buffer

{

long mesg_type;

char mesg_text[100];

} message;

int main()

{

key_t key;

int msgid;

// ftok to generate unique key

// key_t ftok (const char *pathname, int proj_id);

// pathname to existing file, proj_id: any number

// ftok uses the pathname and proj_id to create a unique value

// that can be used by different process to attach to shared memory

// or message queue or any other mechanisms.

key = ftok("~/somefile", 128);

// msgget creates a message queue

// and returns identifier

msgid = msgget(key, 0666 | IPC_CREAT);

message.mesg_type = 1;

printf("Write Data : ");

fgets(message.mesg_text,MAX,stdin);

// msgsnd to send message

msgsnd(msgid, &message, sizeof(message), 0);

// display the message

printf("Data send is : %s \n", message.mesg_text);

return 0;

}

Reader process program:

// C Program for Message Queue (Reader Process)

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/ipc.h>

#include <sys/msg.h>

// structure for message queue

struct mesg_buffer

{

long mesg_type;

char mesg_text[100];

} message;

int main()

{

key_t key;

int msgid;

// ftok to generate unique key

key = ftok("~/somefile", 128);

// msgget creates a message queue

// and returns identifier

msgid = msgget(key, 0666 | IPC_CREAT);

// msgrcv to receive message

msgrcv(msgid, &message, sizeof(message), 1, 0);

// display the message

printf("Data Received is : %s \n",

message.mesg_text);

// to destroy the message queue

msgctl(msgid, IPC_RMID, NULL);

return 0;

}

Message Passing vs Shared Memory

-

Number of system calls made:

-

Message Passing, e.g: via socket requires system calls for each message passed through

send()andreceive()but it is much quicker compared to shared memory to use if only small messages are exchanged. -

Shared memory requires costly system calls (

shmgetandshmat) in the beginning to create the memory segment (this is very costly, depending on the size, pagetable update is required during attaching), but not afterwards when processes are using them.

-

-

Number of procs using:

-

Message passing is one-to-one: only between two processes

-

Shared memory can be shared between many processes.

-

-

Usage comparison:

-

Message passing is useful for sending smaller amounts of data between two processes, but if large data is exchanged then will suffer from system call overhead.

-

Shared memory is costly if only small amounts of data are exchanged. Useful for large and frequent data exchange.

-

-

Synchronization mechanism:

-

Message passing does not require any synchronisation mechanism (because the Kernel will synchronise the two). It will block if required (but can be set to not be blocking too, i.e: block/not block if there’s no message to read but one process requests to read)

-

Shared memory requires additional synchronisation to prevent race-condition issues (burden on the developer). There’s no blocking support. It also has to be freed after they are no longer needed, otherwise will persist in the system until its turned off (check for existing shared memories using

ipcsin terminal)

-

Application: Chrome Browser Multi-process Architecture

Websites contain multiple active contents: Javascript, Flash, HTML etc to provide a rich and dynamic web browsing experience. You may open several tabs and load different websites at the same time. However, some web applications contain bugs, and may cause the entire browser to crash if the entire Chrome browser is just one single huge process.

Google Chrome’s web browser was designed to address this issue by creating separate processes to provide isolation:

- The Browser process (manages user interface of the browser (not website), disk and network I/O); only one browser process is created when Chrome is just opened

- The Renderer processes to render web pages: a new renderer process is created for each website opened in a new tab

- The Plug-In processes for each type of Plug-In

All processes created by Chrome have to communicate with one another depending on the application. The advantage of such multi process architecture is that:

- Each website runs in isolation from one another: if one website crashes, only its renderer crashes and the other processes are unharmed.

- Renderer will also be unable to access the disk and network I/O directly (runs in sandbox: limited access) thus reducing the possibility of security exploits.

- Each process can be scheduled independently, providing concurency and responsiveness.

-

Suppose process 1 and process 2 have successfully attached the shared memory segment.This attachment process causes this shared memory segment will be part of their address space, although the actual address could be different (i.e., the starting address of this shared memory segment in the address space of process 1 may be different from the starting address in the address space of process 2). ↩