Now that we have learned how to execute some commands, it is natural to question why we need to use the command line. What can you do here with CLI that you cannot do through your common graphical user interface?

- Well, it depends on your purpose. There’s a lot of debate on that, some might say that CLI allows you to do tasks fast, but that depends: depends on how well versed you are in using the CLI.

- If you are just a basic user, i.e: browse, watch your favorite tv series, edit photos, or text your friends then chances are you don’t need to use the command line.

- If you’re a computer science graduate who intends to work in the field then CLI is probably your new best friend.

The most common use of the command line is ”system administration” or, basically, managing computers and servers.

This includes installing and configuring software, monitoring computer resources (manage logs, setup cron jobs, daemons), setting up web servers (renaming or modifying thousands of files), and automating processes (setup databases / servers) on many hosts.

Obviously these tasks are repetitive and tedious such that it is impossible to be done manually or one by one via the GUI.

Shell Scripting

In this section, we briefly overview how shell scripts work, eg: .sh, .zsh scripts. A shell script is simply lines of code for the shell to interpret (if you use z/bash shell, you can use z/bash shell script. Since both bash and z are derived from the Bourne shell family, both scripts have similar syntax).

Why do we need to write a shell script? Imagine you want to create thousands of text files (using touch). You wouldn’t want to type the command one by one, but rather just run a script that does this task in one shot.

Task 9

TASK 9: Open nano and type the following:

#!/bin/bash

start_time=$(date +%s)

# the following substitute the arguments as a list, without re-splitting them on whitespace

"$@"

end_time=$(date +%s)

echo "Time elapsed: $(($end_time - $start_time)) seconds"

Then, save it with a name run.sh, and change its mode to be executable: chmod +x run.sh. Now you can run any script and time it. For instance, suppose we have the following python script:

import time

print("Loading.....")

time.sleep(2.5)

print("Done")

Running it with our script will time the execution of the python script above:

bash-3.2$ ./run.sh python3 hello.py

Loading.....

Done

Time elapsed: 3 seconds

bash-3.2$

From the task above, you have just created and run a super simple bash script. Note that the first line is the shebang. Similar to coding in any other language, you can use variables, functions, conditional statements, loops, comparisons, etc in your bash script. You can learn more in your own time, and see examples of awesome bash scripts.

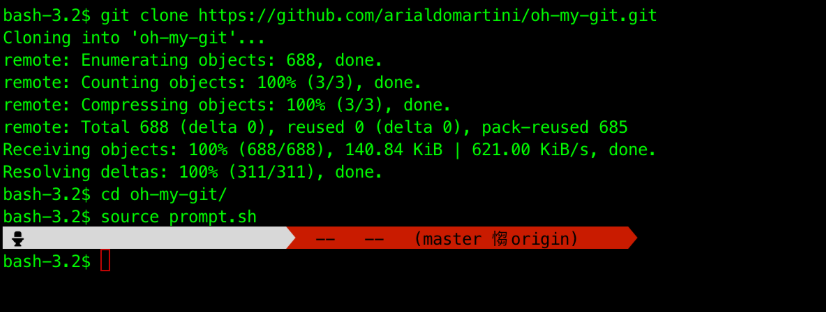

For example, you can customize your prompt in a git repo:

Compiling Programs

We can also compile and run programs from the command line, provided that you have the compiler or interpreter, e.g. python3, gcc, or javac.

Task 10

TASK 10: To demonstrate this idea, download this starter code: git clone https://github.com/natalieagus/makeFileDemo.git

We require you to have gcc for this task. If your OS doesn’t have it, you can install it with (Ubuntu):

sudo apt update

sudo apt install build-essential

Read all the .c and .h files and get an understanding of what each file is supposed to do. To compile the files and run the executable:

- Navigate to this directory and type the command:

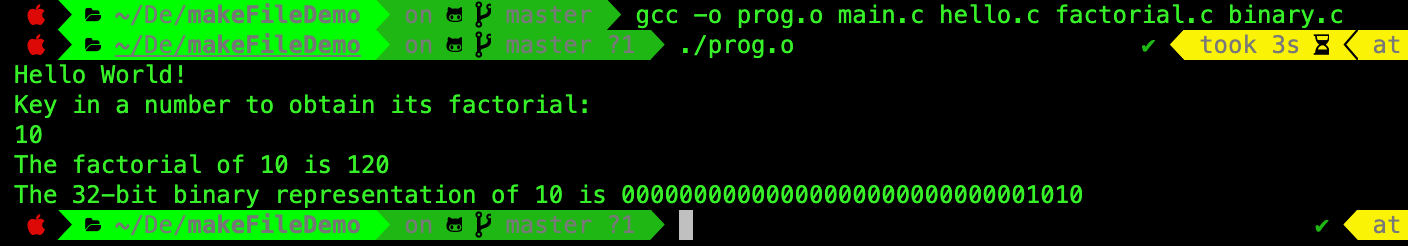

gcc -o prog.o main.c hello.c factorial.c binary.c - And then execute by typing

./prog.o

Experiment with the program a little bit. You should see a prompt for you to key in a number. Simply type something and press enter.

In case you haven’t connected the dots, gcc compiles all the input argument files: main.c, hello.c, factorial.c, binary.c and produces a binary output (this is what -o means) named prog.o which you can execute using ./prog.o .

Makefile

In this simple context, it is feasible to type out the source file one by one each time you want to compile your program. However in a large scale project with thousands of files, it is very tedious to type the compilation command all the time. Hence, the make command allows us to compile these files more easily. It requires a special file called the makefile.

- Now instead of typing gcc and all that above, type

makeinstead - After executing

make, realize that prog.o is made. You can run the executable in the terminal by typing./prog.oor by simply clicking that executable in your shell GUI (your desktop).

Lets now examine how makefile is made.

# Define required macros here

REMOVE = rm

CC = gcc

DEPENDENCIES = main.c hello.c factorial.c binary.c

OUT = prog.o

# Explicit rules, all the commands you can call with make

# (note: the <tab> in the command line is necessary for make to work)

# target: dependency1 dependency2 ...

# <tab> command

#Called by: make prg

#also executed when you just called make. This calls the first target.

prog: main.c hello.c factorial.c binary.c

gcc -o prog.o main.c hello.c factorial.c binary.c

prog1: $(DEPENDENCIES)

$(CC) $(DEPENDENCIES) -o $(OUT)

prog2: main.o hello.o factorial.o binary.o

gcc -o prog2 main.o hello.o factorial.o binary.o

##make clean will remove myexecoutprog.o from the directory

clean:

rm prog.o

clean1:

$(REMOVE) $(OUT)

clean2:

rm prog2 *.o

#Implicit rules

main.o : main.c functions.h

factorial.o: factorial.c functions.h

hello.o: hello.c functions.h

binary.o: binary.c functions.h

- The first four lines are the MACROS, which are convenient shorthands you can make to make your life easier when typing these codes.

- Afterwards, there’s a bunch of explicit rules that you can call using make. So in this makefile, you can try calling these in sequence and observe what each rule do:

make progmake prog1make cleanmake clean1

Recompilation

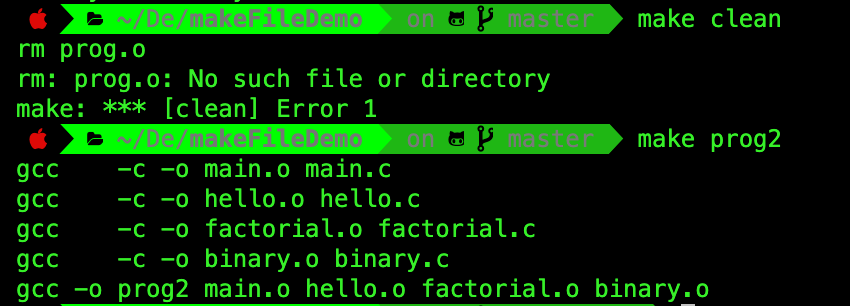

Run this command consecutively:

make cleanmake prog2

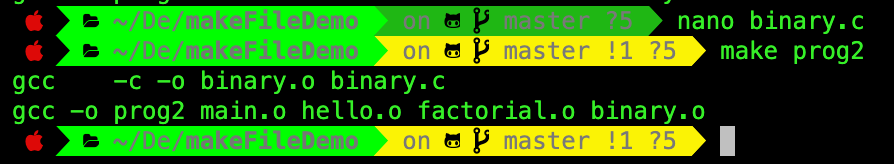

You should see the following output on your terminal as a result of make prog2:

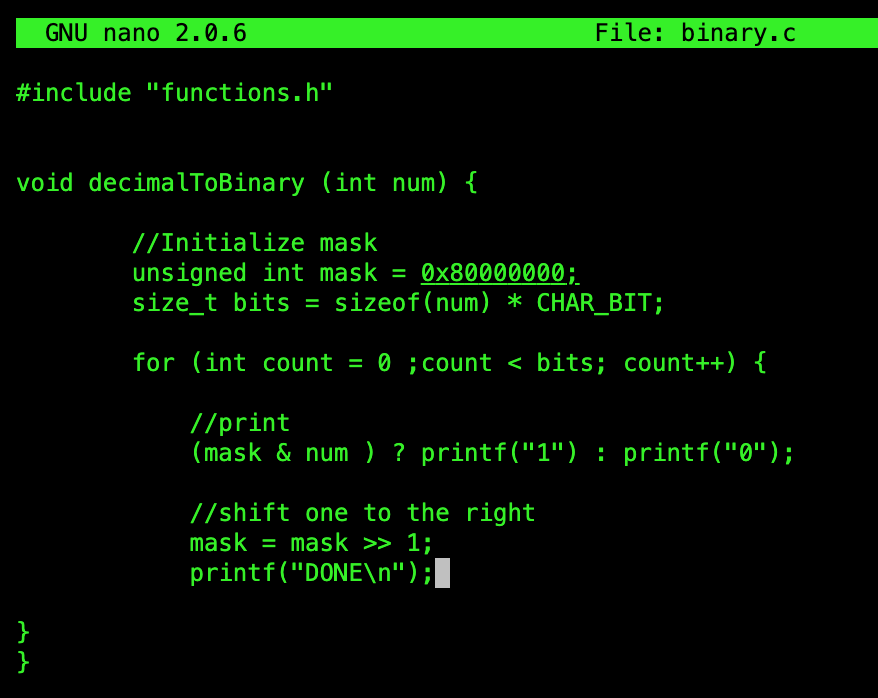

Now open binary.c in the nano and add another instruction in it, eg a printf function at the end:

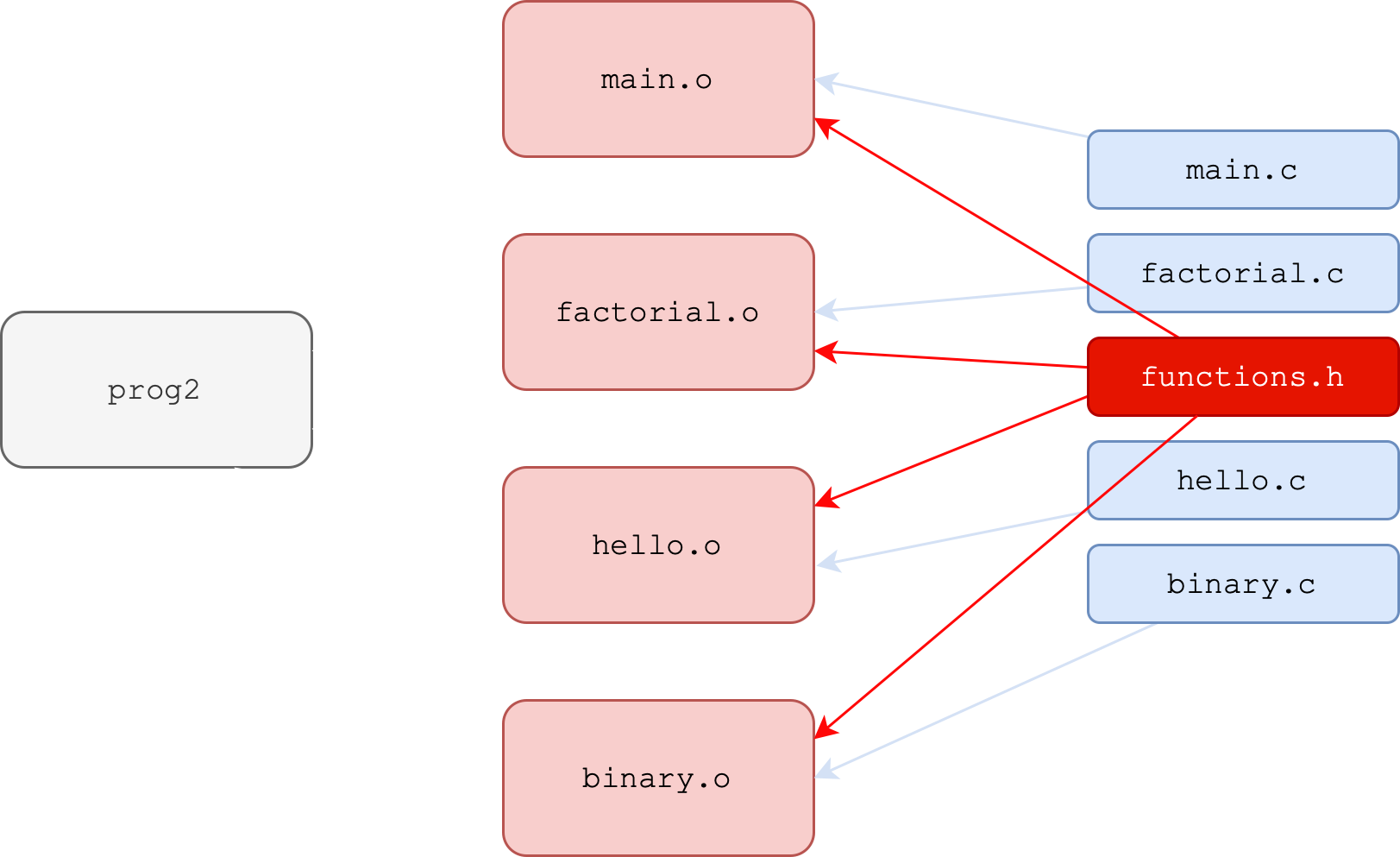

When you try to make prog2 again, the output shows that we only compile files concerning binary.c and not all files are recompiled. Scroll down to the end of the makefile, and notice there’s implicit rules there to determine dependencies.

This gives more efficient compilation. It only recompiles parts that are changed. The Figure below shows the data dependency between files that are specified in the makefile.

Note: File_1 → File_2 means that File_2 depends on File_1.